- Home

- About Journals

-

Information for Authors/ReviewersEditorial Policies

Publication Fee

Publication Cycle - Process Flowchart

Online Manuscript Submission and Tracking System

Publishing Ethics and Rectitude

Authorship

Author Benefits

Reviewer Guidelines

Guest Editor Guidelines

Peer Review Workflow

Quick Track Option

Copyediting Services

Bentham Open Membership

Bentham Open Advisory Board

Archiving Policies

Fabricating and Stating False Information

Post Publication Discussions and Corrections

Editorial Management

Advertise With Us

Funding Agencies

Rate List

Kudos

General FAQs

Special Fee Waivers and Discounts

- Contact

- Help

- About Us

- Search

Current Chemical Genomics and Translational Medicine

(Discontinued)

ISSN: 2213-9885 ― Volume 12, 2018

Comparative Docking Assessment of Glucokinase Interactions with its Allosteric Activators

Vandana Kumari, Chenglong Li*

Abstract

Glucokinase (GK) is expressed in multiple organs and plays a key role in hepatic glucose metabolism and pancreatic insulin secretion. GK could indeed serve as pacemaker of glycolysis and could be an attractive target for type 2 diabetes (T2D). The recent preclinical data of first GK activator RO-28-1675 has opened up a new field of GK activation as a powerful tool in T2D therapies. The GK allosteric site is located ~20Å away from glucose binding site. Chemical structure of Glucokinase activators (GKA) includes three chemical arms; all consisting of cyclic moiety and joined in a shape resembling the letter Y. In this study, comparative docking assessment using Autodock4 revealed that the three arms bind to three aromatic/hydrophobic subpockets at the allosteric site. Our dockings have overall consistency with experimental data in both docking modes and simulated binding free energies, and offer insights on understanding GK/GKA interactions and further GKA design. Specifically, for the first pocket, involvement of Arg63 as key residue in two specific hydrogen-bond formations with all allosteric activators defines the binding feature; for the second pocket, it has the most diverse binding interactions, mostly aromatic, hydrophobic and multiple hydrogen bonds. The site has the best potential for further GKA optimization by utilizing aromatic heterocycles and hydrogen bond forming linkers to build the GKA 2nd arm.

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2008Volume: 2

First Page: 76

Last Page: 89

Publisher Id: CCGTM-2-76

DOI: 10.2174/1875397300802010076

Article History:

Received Date: 15/8/2008Revision Received Date: 17/11/2008

Acceptance Date: 23/11/2008

Electronic publication date: 30/12/2008

Collection year: 2008

open-access license: This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted, non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the work is properly cited.

* Address correspondence to this author at the Division of Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy, College of Pharmacy, The Ohio State University, 500 West 12th Ave., Columbus, OH 43210, USA; Tel: 614-247-8786; Fax: 614-292-2435; E-mail: li.728@osu.edu

| Open Peer Review Details | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Manuscript submitted on 15-8-2008 |

Original Manuscript | Comparative Docking Assessment of Glucokinase Interactions with its Allosteric Activators | |

INTRODUCTION

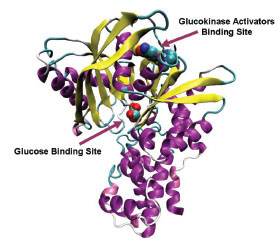

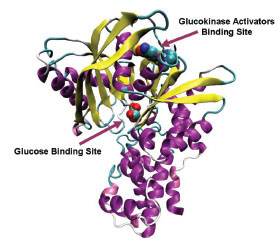

Glucokinase (GK) is one of the four hexokinase isozymes present in hepatocytes and in pancreatic β-cells that metabolize glucose to glucose-6-phosphate [1Printz RL, Mangnuson MA, Granner DK. Mammalian glucokinase Annu Rev Nutr 1993; 13: 463-96.]. In pancreatic β-cells, GK is the rate limiting enzyme in glucose metabolism and determines the rate of glucose induced insulin secretion and acts as an ideal glucose sensor [2Matschinsky FM, Magnuson MA, Zelent D, et al. The network of glucokinase-expressing cells in glucose homeostasis and the potential of glucokinase activators for diabetes therapy Diabetes 2006; 55: 1-12.]. In liver, GK activity determines the rate of glucose usage and glycogen synthesis; it follows Non-Mechaelis-Menton kinetics which means that no inhibition of GKs with product of the reaction, glucose-6-phosphate [3Matschinsky FM, Glaser B, Magnuson MA. Pancreatic beta-cell glucokinase: closing the gap between theoretical concepts and experimental realities Diabetes 1998; 47: 307-15.]. Crystal structure of GK in complex with glucose and Glucokinase activator (GKA) reveals a palm shape topology which contains two domains of unequal size; the large and the small. These two domains are separated by a deep cleft, which forms the active site for glucose phosphorylation. A hydrophobic allosteric pocket is present ~20 Å distal to the catalytic site, which is exposed to solvent when the kinase is bound to glucose in its ‘closed’ catalytically active state. In glucose unbound form (‘open form’), hydrophobic pocket is buried within the opposed large and small domains. GKAs bind at allosteric site and directly activate GK [4Kamata K, Mitsuya M, Nishimura T, Eiki J, Nagata Y. Structural basis for allosteric regulation of the monomeric allosteric enzyme human glucokinase Structure 2004; 12: 429-38.]. The glucose binding site and the allosteric binding site of GK are shown in Fig. (1 ).

).

Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) is characterized by defect in action and secretion of insulin; which leads to excessive hepatic glucose production and decreased glucose-induced release from the pancreatic β–cells. In spite of the efforts of many research groups, no single oral antidiabetic drug is capable of achieving acceptable, long-lasting glycemic control [5Gershell L. Type 2 diabetes market Nat Rev Drug Discov 2005; 4(5): 367-8.]. Indeed, the use of combination therapy is thought to offer better glycemic control relative to monotherapy but there are some unwanted side effects of combination therapy [6Wagman AS, Nuss JM. Current therapies and emerging targets for the treatment of diabetes Curr Pharm Des 2001; 7(6): 417-50.]. Thus, there is growing need of safe and more efficient novel drugs. GK would be an ideal drug target for T2D diseases because of its high impact in glucose homeostasis, and its activation results in lower blood glucose level irrespective of the cause of hyperglycemia [7Sarabu R, Grimsby J. Targeting glucokinase activation for the treatment of type 2 diabetes--a status review Curr Opin Drug Discov Dev 2005; 8(5): 631-37.]. Discovery and promising preclinical data of the first allosteric GK activator RO-28-1675 has intensifies interest in GKAs [8Grimsby J, Sarabu R, Corbett WL, et al. Allosteric activators of glucokinase: potential role in diabetes therapy Science 2003; 301(5631): 370-73., 9Daniewski AR, Liu W, Radinov RN. Inventors, Process for the preparation of a glucokinase activator International Patent WO 2007115968 2000 Oct; ]. Many research groups have reported small molecule glucokinase activators which are thought to enhance glycemic control by dual mechanism of increased pancreatic insulin secretion and increased hepatic glucose metabolism [9Daniewski AR, Liu W, Radinov RN. Inventors, Process for the preparation of a glucokinase activator International Patent WO 2007115968 2000 Oct; -17Brocklehurst KJ, Payne VA, Davies RA, et al. Stimulation of hepatocyte glucose metabolism by novel small molecule glucokinase activators Diabetes 2004; 53(3): 535-41.]. Therefore, the ability of GKAs to influence multiple organs could provide greater efficacy as a monotherapy. In this study, we report comparative docking studies of GKAs. The aim of this study is to understand interactions involved in the binding of GKAs to glucokinase and to offer insights into activation pattern of glucokinase by its allosteric activators. This study will provide further understanding of the mechanism of glucokinase activation and would enable the design of new GKAs capable of selectively activating GK in the treatment of T2D.

METHODS

Docking Calculations

We assembled from literature a list of Glucokinase activators [9Daniewski AR, Liu W, Radinov RN. Inventors, Process for the preparation of a glucokinase activator International Patent WO 2007115968 2000 Oct; -17Brocklehurst KJ, Payne VA, Davies RA, et al. Stimulation of hepatocyte glucose metabolism by novel small molecule glucokinase activators Diabetes 2004; 53(3): 535-41.] and classified them into four structural classes. RESP charges for each ligand were calculated at HF/6-31+G(d) level of theory using Gaussian03 [18Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, et al. Gaussian 03. Wallingfod CT: Gaussian Inc 2004 .]. Sander module of Amber9 was used to calculate solvation energy of the ligands [19Wang J, Wolf RM, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA, Case DA. Development and testing of a general amber force field J Comput Chem 2004; 25(9): 1157-74.]. All ligands were docked to crystal structure of active conformation of human glucokinase (PDB ID: 1V4S) using AutoDock software, version 4.0. [20Sanner MF. Python: A programming language for software integration and development J Mol Graph Model 1999; 17(1): 57-61., 21Huey R, Morris GM, Olson AJ, Goodsell DS. An empirical free energy force field with charge-based desolvation and intramolecular evaluation J Comp Chem 2007; 28: 1145-52.]. Ligand coordinate files were generated by Insight II 2.1 package (Biosym Technologies Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All ligands shown in Table 1 were docked to active models of the Glucokinase, using the Lamarckian Genetic algorithm (LGA) [22Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, et al. Automated Docking Using a Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and an Empirical Binding Free Energy Function J Comput Chem 1998; 19: 1639-62.]. The grid maps representing the protein were calculated using the AutoGrid4. A cubic box was built around the protein with 61x61x67 grid points; a spacing of 0.375 between the grid points was used. The protein was centered on the geometric center prior to docking. All calculations and docking simulations were carried out at Ohio Supercomputer Center Glenn Cluster. Resulting conformations that have less than or equal to 1.5 Å root mean square deviation were clustered. In addition to resulting docking modes, AutoDock also calculates an affinity constant for each ligand-receptor configuration.

RESULTS

Binding Pattern of Glucokinase Activators at Allosteric Site

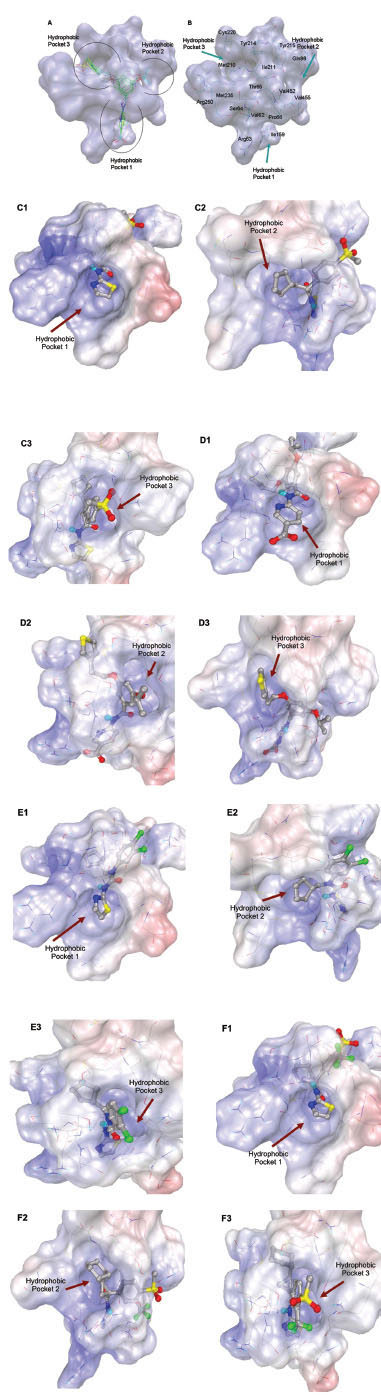

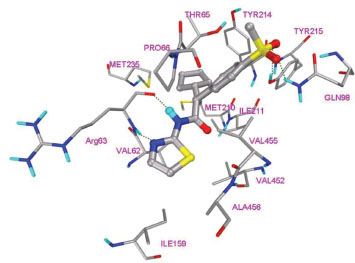

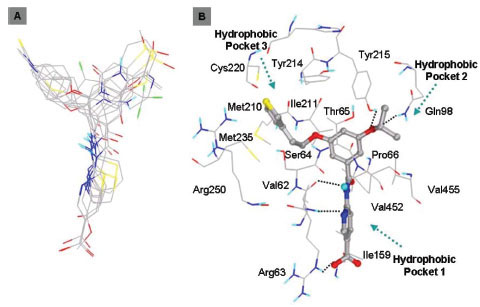

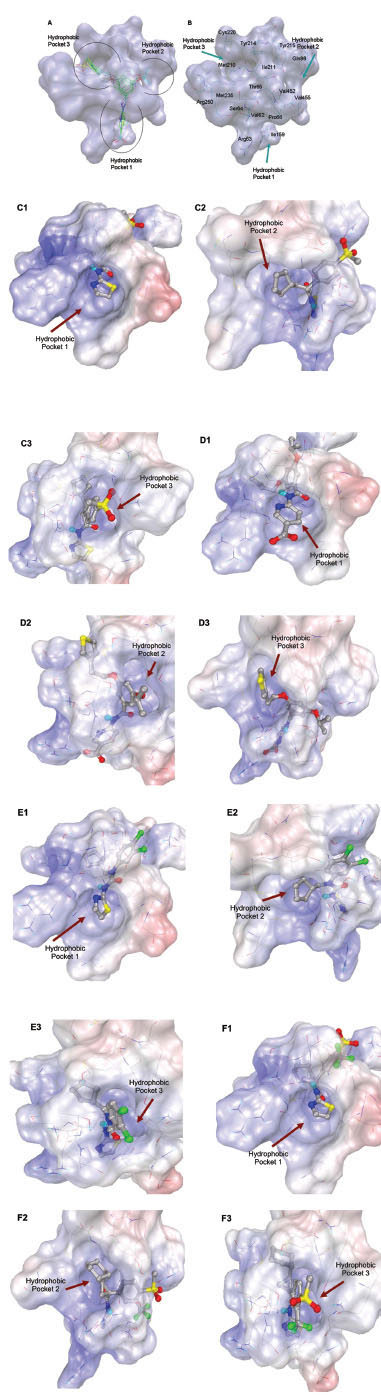

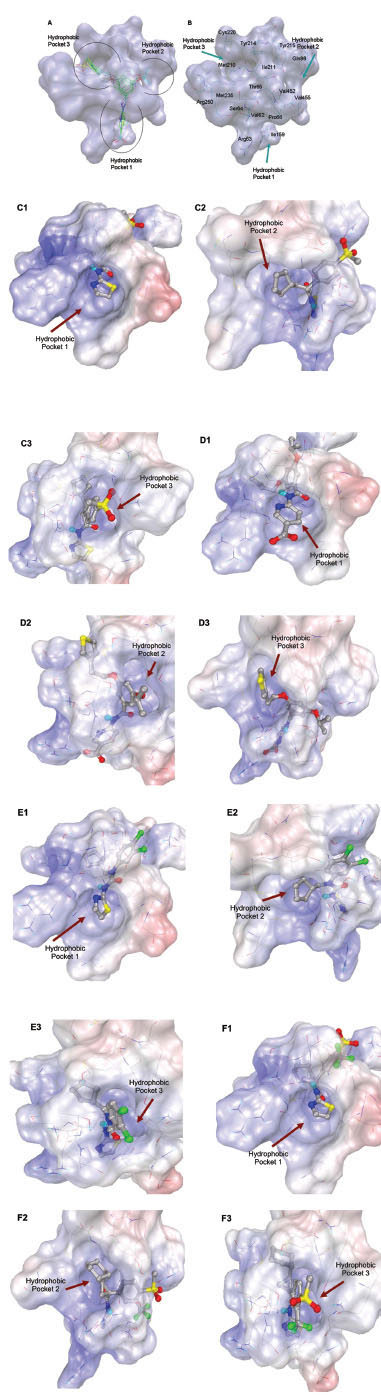

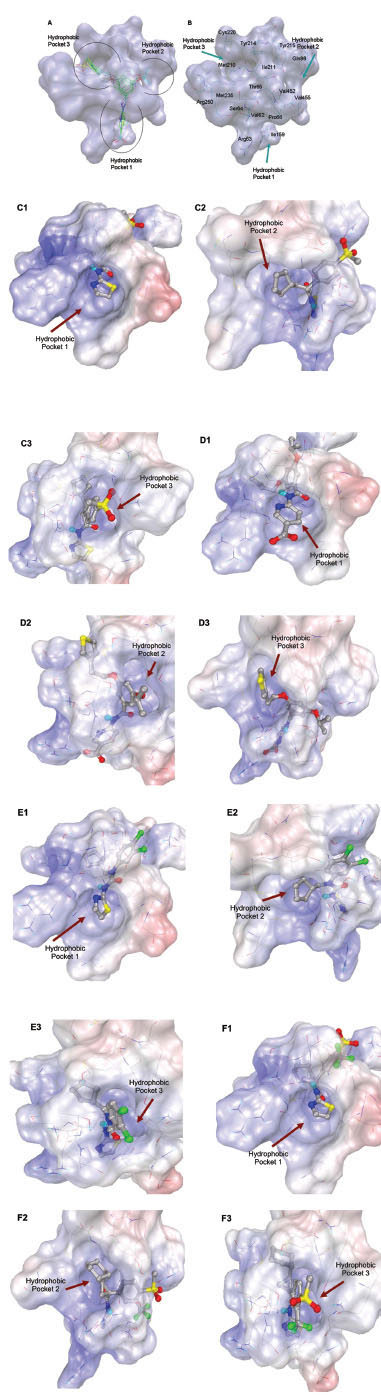

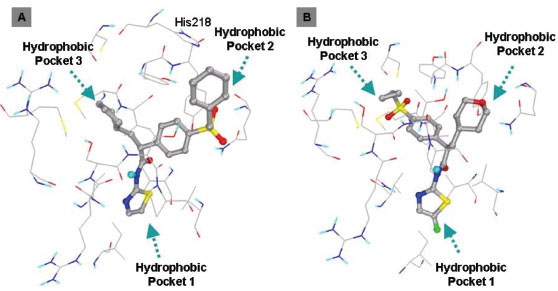

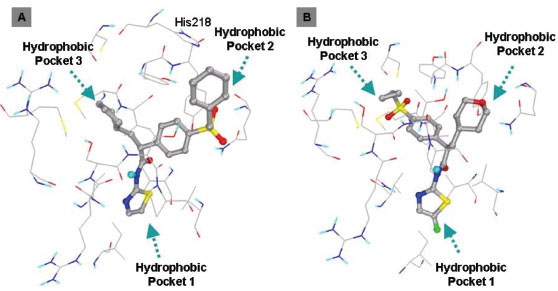

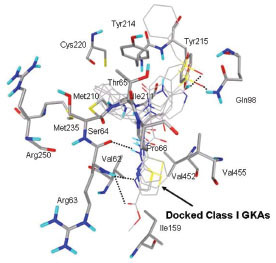

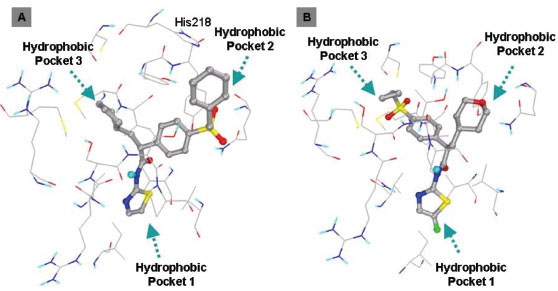

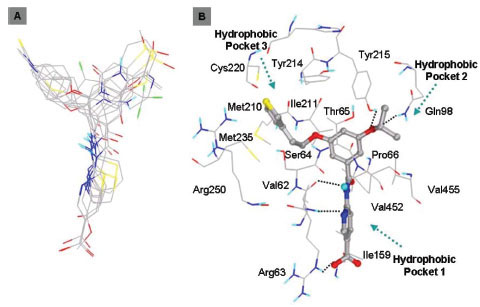

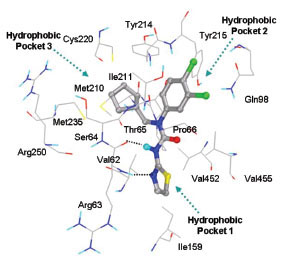

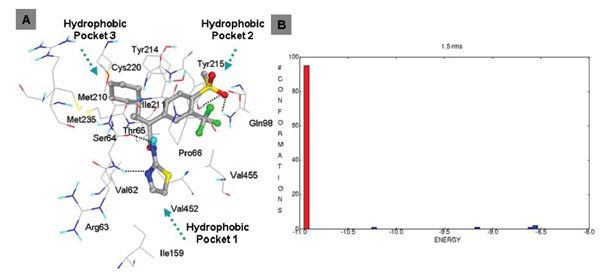

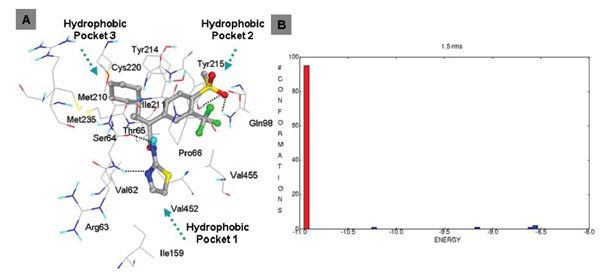

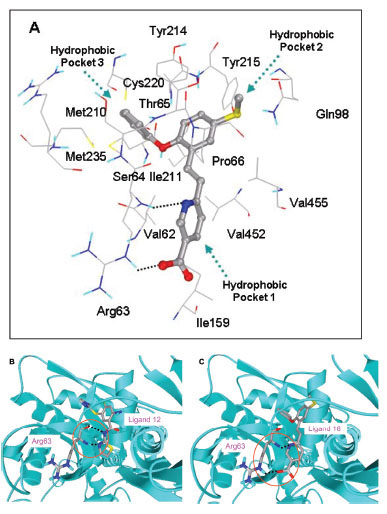

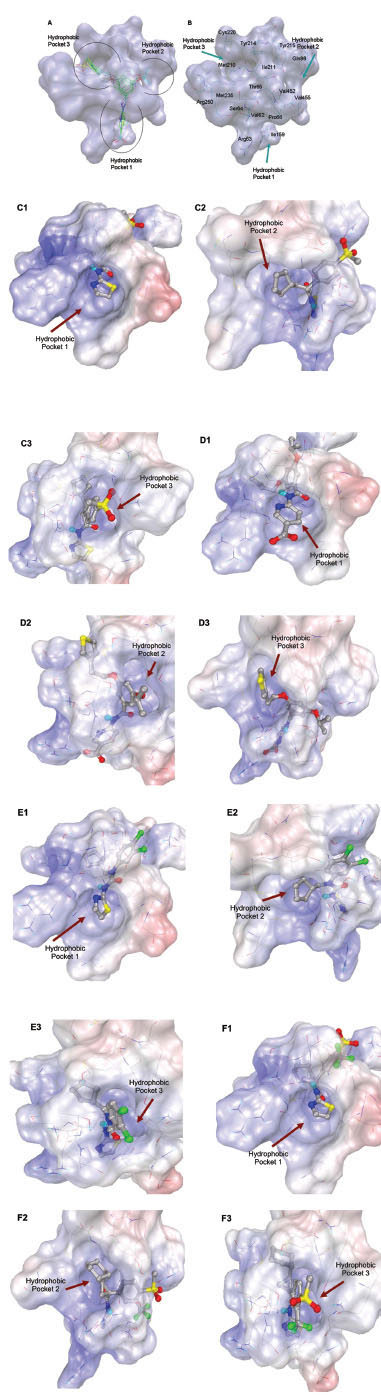

In this study, flexible-ligand docking was performed using energetically optimized ligands. Table 1 shows the simulated free energy of binding (ΔGbind) and experimental EC50 [9Daniewski AR, Liu W, Radinov RN. Inventors, Process for the preparation of a glucokinase activator International Patent WO 2007115968 2000 Oct; -17Brocklehurst KJ, Payne VA, Davies RA, et al. Stimulation of hepatocyte glucose metabolism by novel small molecule glucokinase activators Diabetes 2004; 53(3): 535-41.] values. For the docking studies, we classified GKAs into four classes. Class I GKAs includes amide-based chiral ligands, this class of activators has flexible three arms containing cyclic moiety. These arms are joined in a shape resembling letter Y. Class II GKAs includes amide-based achiral ligands; this class of activators has a multi-substituted cyclic ring which connects three arms of the ligands. The substitutions on the rings are involved in packing interactions at the allosteric binding site. Class III GKAs includes urea-derivatives GKAs; this class resembles class I GKAs in structural orientation. Class IV GKAs include miscellaneous ligands which contains some other groups relative to other classes of GKAs. Overall, all GKAs appear to bind, in a consistent mode, between a large hydrophobic patch consisted of two perpendicular α-helices (α5 and α13) and a well solvated loop connector I (Arg63-Ser64-Thr65-Pro66-Gln67-Gly68) in the junction of the two GK domains. Whereas in GK apo structure, there is no allosteric site as the two α-helices packing to each other in parallel and the loop is only partially solvated and tucked in a pseudo-helix form against the two helices. These loop residues in other non-allosteric hexokinase structures pack closely against neighboring structural elements all the time. In general, a large number of hydrophobic binding interactions contribute to the binding energies of the activators. The three arms of GKAs fit well in the three hydrophobic pockets (Fig. 2A ) of the glucokinase formed at the allosteric site. Amino acid residues involved in binding interactions are shown in Fig. (2B

) of the glucokinase formed at the allosteric site. Amino acid residues involved in binding interactions are shown in Fig. (2B ). Hydrophobic Pocket 1 contains Val62, Ile159, Val452, Val255 hydrophobic amino acids and polar Arg63 amino acid residue. In most cases, a defined feature is the two hydrogen bonds between Arg63 and GKA. One is Arg63 carbonyl to GKA amide; the other is Agr63 amide to the nitrogen of the GKA thiazole. It seems that an amide linked to a thiazole or pyridine binds to the pocket 1 well. Pro66, Val455 and Tyr215 makes hydrophobic pocket 2 and hydrophobic pocket 3 is formed by Met210, Met235 and Tyr214 amino acid residues. Electrostatic potential surface of allosteric site was generated using APBS [23Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 10037-41.] and interactions of the ligand’s arms with their respective allosteric hydrophobic pocket are shown in Fig. (2

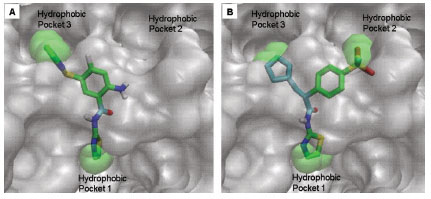

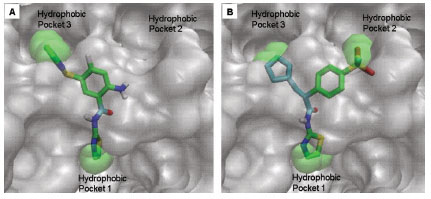

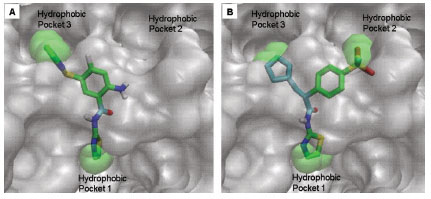

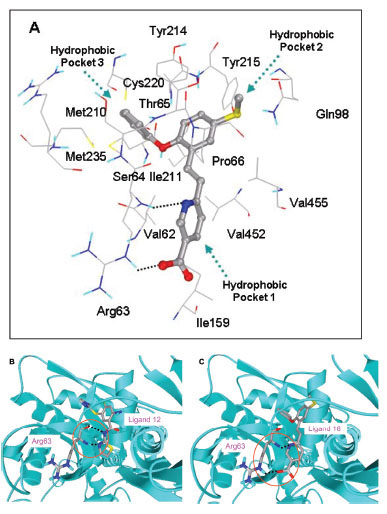

). Hydrophobic Pocket 1 contains Val62, Ile159, Val452, Val255 hydrophobic amino acids and polar Arg63 amino acid residue. In most cases, a defined feature is the two hydrogen bonds between Arg63 and GKA. One is Arg63 carbonyl to GKA amide; the other is Agr63 amide to the nitrogen of the GKA thiazole. It seems that an amide linked to a thiazole or pyridine binds to the pocket 1 well. Pro66, Val455 and Tyr215 makes hydrophobic pocket 2 and hydrophobic pocket 3 is formed by Met210, Met235 and Tyr214 amino acid residues. Electrostatic potential surface of allosteric site was generated using APBS [23Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 10037-41.] and interactions of the ligand’s arms with their respective allosteric hydrophobic pocket are shown in Fig. (2 ) C1-F3. Ligands that pack adequately to these three hydrophobic pockets show higher binding energies compared to the ligands that lack one of the packing interactions, especially for the pocket 2. Ligands having three arms show more efficient interactions at allosteric binding pocket because of the proper accommodation of the ligand as compared to ligands lacking one of the arms (Fig. 3A

) C1-F3. Ligands that pack adequately to these three hydrophobic pockets show higher binding energies compared to the ligands that lack one of the packing interactions, especially for the pocket 2. Ligands having three arms show more efficient interactions at allosteric binding pocket because of the proper accommodation of the ligand as compared to ligands lacking one of the arms (Fig. 3A and B

and B ). Involvement of allosteric site residues in different kind of interactions with ligands is shown in Table 2.

). Involvement of allosteric site residues in different kind of interactions with ligands is shown in Table 2.

Comparative Binding Interactions of GKAs

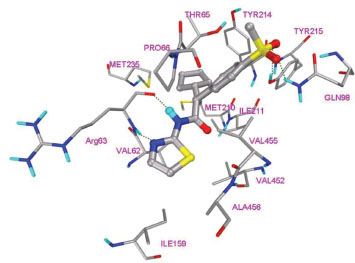

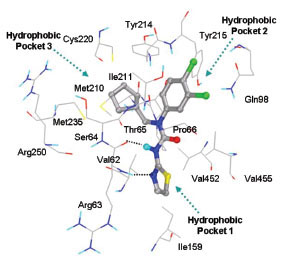

Class I: Amide-Based Chiral GKAs

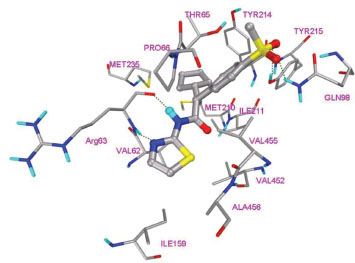

The three cyclic moieties joined in Y shape contain amide linkage along the stem of the Y, the amide NH acts as hydrogen bond donor and involved in specific hydrogen bond formation with Arg63 backbone carbonyl O. Heterocyclic group containing N at position two connected to the amide NH of ligand makes another specific hydrogen bond formation with the Arg63 backbone NH (Fig. 4 ). This class of ligands contains cyclopentyl or cyclohexyl (R3) as one arm of the ligand and shows packing in hydrophobic pocket 3 (Fig. 6A

). This class of ligands contains cyclopentyl or cyclohexyl (R3) as one arm of the ligand and shows packing in hydrophobic pocket 3 (Fig. 6A ). R3 group nestles between two Met210, Met235 and Tyr214 side chain at allosteric site. Fig. (4

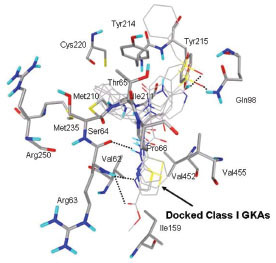

). R3 group nestles between two Met210, Met235 and Tyr214 side chain at allosteric site. Fig. (4 ) shows binding interactions of ligand 1 (class I GKA). Ligands containing hydrogen bond acceptor group in R2 makes additional hydrogen bond formation with Tyr215 and Gln98. Aligned binding modes of class I ligands are shown in Fig. (5

) shows binding interactions of ligand 1 (class I GKA). Ligands containing hydrogen bond acceptor group in R2 makes additional hydrogen bond formation with Tyr215 and Gln98. Aligned binding modes of class I ligands are shown in Fig. (5 ). Ligand 3 shows three hydrogen bond formations with Arg63 due to presence of ester group in thiazole ring. Val62, Pro66, Ile159, Met210, Ile211, Tyr214, Met235, Cys220, Val452, Val455, Ala456 are the main residues involved in hydrophobic interactions with this class of ligands.

). Ligand 3 shows three hydrogen bond formations with Arg63 due to presence of ester group in thiazole ring. Val62, Pro66, Ile159, Met210, Ile211, Tyr214, Met235, Cys220, Val452, Val455, Ala456 are the main residues involved in hydrophobic interactions with this class of ligands.

|

Fig. (6) A. Binding mode of ligand 5. B. Binding mode of ligand 7. Ligands are shown in ball and stick display. Amino acids are shown in line view. |

|

Fig. (5) Aligned docked mode of ligands of class I GKAs. Ligands are shown in lines and amino acid residues are shown in licorice display. |

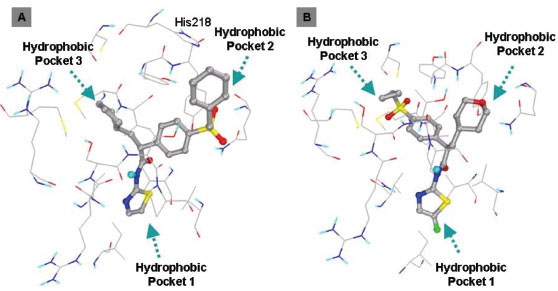

Ligand 5 and 7 are more hydrophobic in nature as compared to other ligands of class I GKA because of the presence of additional cyclophenyl and cyclopropyl groups respectively. The binding modes of ligand 5 and 7 are shown in Fig. (6 ). These ligands bind in different mode as compared to other ligands of this class because of presence of additional hydrophobic cyclic groups. Cyclophenyl ring of ligand 5 shows hydrophobic interaction with His218 and binds in hydrophobic pocket 2, this additional interaction lowers binding energy approximately by 2 kcal/mol as compared to other ligands and makes it more potent GKA. Cyclopropyl ring of ligand 7 binds in hydrophobic pocket 3 and shows hydrophobic interactions with Met210, Met235 and Tyr214. This is the second most potent ligand of class I GKA. AutoDock calculated binding energy of ligand 7 is -9.7 kcal/mol, which is 0.4 kcal/mol higher compared to experimental value. Experimental EC50 of other ligand of this class is not available so it’s hard to compare binding energy estimated by autodock.

). These ligands bind in different mode as compared to other ligands of this class because of presence of additional hydrophobic cyclic groups. Cyclophenyl ring of ligand 5 shows hydrophobic interaction with His218 and binds in hydrophobic pocket 2, this additional interaction lowers binding energy approximately by 2 kcal/mol as compared to other ligands and makes it more potent GKA. Cyclopropyl ring of ligand 7 binds in hydrophobic pocket 3 and shows hydrophobic interactions with Met210, Met235 and Tyr214. This is the second most potent ligand of class I GKA. AutoDock calculated binding energy of ligand 7 is -9.7 kcal/mol, which is 0.4 kcal/mol higher compared to experimental value. Experimental EC50 of other ligand of this class is not available so it’s hard to compare binding energy estimated by autodock.

Class II: Amide-Based Achiral GKAs

This class of GKAs lacks chiral carbon connected to amide group. Multi-substituted cyclic ring is present which acts as stem of Y letter and substituents on this ring orient in the shape of Y. Lack of chiral carbon center in these ligands makes ligands less flexible. Hydrophobic pocket 2 accommodates smaller hydrophobic groups while hydrophobic pocket 3 accommodates bigger hydrophobic groups. Fig. (7 ) shows binding mode of this class of ligands. This class also shows specific hydrogen bond formation with the Arg63 backbone. Ligands having carboxyl group attached to heterocyclic ring shows additional hydrogen bond formation with the Arg63 side chain and contributes to the binding energy. Tyr215 and Gln98 are involved in hydrogen bond formation with ether group. Amino group is present instead of ether group in ligand 10 and this amino group also shows hydrogen bond formation with Tyr215 and Gln98 amino acids. Crystal structure of ligand 10 bound at allosteric site of GK is present and our docking mode shows similar kind of binding interactions as crystal structure.

) shows binding mode of this class of ligands. This class also shows specific hydrogen bond formation with the Arg63 backbone. Ligands having carboxyl group attached to heterocyclic ring shows additional hydrogen bond formation with the Arg63 side chain and contributes to the binding energy. Tyr215 and Gln98 are involved in hydrogen bond formation with ether group. Amino group is present instead of ether group in ligand 10 and this amino group also shows hydrogen bond formation with Tyr215 and Gln98 amino acids. Crystal structure of ligand 10 bound at allosteric site of GK is present and our docking mode shows similar kind of binding interactions as crystal structure.

Class III: Urea Derivatives GKAs

This class of GKAs resembles structurally with class I GKAs. Binding modes of the ligands are also similar in orientation as Class I GKAs. This class of ligands also shows specific hydrogen bond formations with Arg63 carbonyl O and NH to NH of amide and N of thiazole, respectively. R3 group lies in hydrophobic pocket 3 and makes hydrophobic interactions with Val62, Ile159 Met210, Ile211, Met235, Val452, amino acid residues. Tyr215 is involved in aromatic/hydrophobic interaction at hydrophobic pocket 2 and also forms hydrogen bonds with ligands containing hydrogen bond acceptor group in R2. Fig. (8 ) shows binding mode of ligand 15.

) shows binding mode of ligand 15.

|

Fig. (8) Binding mode of ligand 15 (Class III) at the allosteric site of GK. |

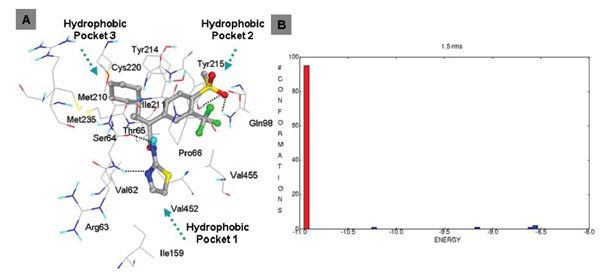

Class IV: Miscellaneous GKAs

This class of GKAs contains ligands which have some unique groups. Ligand 19 and 20 contains cyclopropyl group connecting three arms. Docking studies of ligand19 shows comparable binding energy to the experimental value. Clustering of docked conformations also gave high confidence, 95% of the docked conformations fall in one cluster with 1.5 Å RMSD tolerance. Docking mode and clustering histogram of ligand 19 are shown in Fig. (9 ). Thr65 is involved in hydrogen bond formation with O of methyl sulfone group. Ligand 18 does not contain amide group, this is structurally different from all other ligands. Docking studies of this ligand also shows involvement of Arg63 in two specific hydrogen bond formation with N of pyridine and carbonyl group of carboxylic group of ligand 18 (Fig. 10

). Thr65 is involved in hydrogen bond formation with O of methyl sulfone group. Ligand 18 does not contain amide group, this is structurally different from all other ligands. Docking studies of this ligand also shows involvement of Arg63 in two specific hydrogen bond formation with N of pyridine and carbonyl group of carboxylic group of ligand 18 (Fig. 10 ). This suggests that Arg63 is highly conserved residue which is specifically involved in hydrogen bond formation with GKAs. Hydrophobic interactions for this class were similar to that of other classes of GKAs.

). This suggests that Arg63 is highly conserved residue which is specifically involved in hydrogen bond formation with GKAs. Hydrophobic interactions for this class were similar to that of other classes of GKAs.

|

Fig. (9) A. Binding mode of ligand 19 (class IV). B. Clustering of docked conformations. |

|

Fig. (10) Binding interactions of ligand 18 (A). Hydrogen bond formation with Arg63 amino acid (B, C). |

DISCUSSION

Docking studies of GKAs identify involvement of Arg63 as key residue in hydrogen bond formation with all classes of ligands. Therefore, for R1 group, a hydrogen bond donor as linker and a heterocycle as hydrogen bond acceptor seem the best choice. Van der Walls packing interactions contribute most favorably to the binding energies of the ligands. Three hydrophobic cavities are formed by van der Walls packing interactions between ligand and allosteric site of GK and the ligands show three arms consisting of cyclic moieties. Each arm packs in the hydrophobic pocket. Ligands having less than three arms show less hydrophobic binding interactions and will lead to less potency. Val62, Ile159, Met210, Ile211, Cys220, Met235, Val452, makes floor of the allosteric binding site. These hydrophobic residues are exclusively involved in van der Walls packing with all classes of ligands. Tyr214 and Tyr215 are involved in both aromatic and hydrophobic interactions. Ligands having more favorable interactions with Tyr214 show stronger binding energies as it exerts effect on both Pockets 2 and 3. Ligand’s arm having longer chain with hydrophobic cyclic ring binds more favorably in hydrophobic pocket 3 and contributes to the potency of the ligand. R2 group of class II GKAs have two arms, longer arm binds in hydrophobic pocket 3 while shorter arm binds in hydrophobic pocket 2. Fig. (2 ) shows hydrophobic pockets and binding of class II GKAs to the hydrophobic pocket. Ligand 14 shows addition hydrogen bond formation between Arg250 and SO2CH3 group of ligand. This interaction also increases potency of the ligand. Ligands containing terminal carboxylic group show additional hydrogen bond formation with the Arg63 side chain and adds towards binding energy of the activators. R1 and R2 groups of Ligands 10 and 11 are different but both shows similar binding mode and similar binding energy. This could be due to involvement of same amino acid residues in both binding interactions. Ligand 8 shows involvement of Thr65 backbone in the hydrogen bond formation with N of bicyclic ring, but this ligand shows lowest binding interactions among all classes of GKAs, this could be due to less interaction with the key hydrophobic side chains.

) shows hydrophobic pockets and binding of class II GKAs to the hydrophobic pocket. Ligand 14 shows addition hydrogen bond formation between Arg250 and SO2CH3 group of ligand. This interaction also increases potency of the ligand. Ligands containing terminal carboxylic group show additional hydrogen bond formation with the Arg63 side chain and adds towards binding energy of the activators. R1 and R2 groups of Ligands 10 and 11 are different but both shows similar binding mode and similar binding energy. This could be due to involvement of same amino acid residues in both binding interactions. Ligand 8 shows involvement of Thr65 backbone in the hydrogen bond formation with N of bicyclic ring, but this ligand shows lowest binding interactions among all classes of GKAs, this could be due to less interaction with the key hydrophobic side chains.

Ligand 5 (class I GKA) shows highest binding interactions among all classes of GKAs. This ligand contains benzyl group instead of methyl group of SO2CH3 group of ligand 1, 6, 14, 16, 17, 19, 20, and 21 and makes unique hydrophobic interaction with His218 (Fig. 6A ). The Oxygen of methylsulfonyl (SO2CH3) group forms hydrogen bond with Tyr215 and Gln98. All other interactions are similar to other members of this class. The binding energy improves over 2 kcal/mol because of the unique hydrophobic interaction with His218. Ligand 7 contains cyclopropyl group instead of benzyl group of ligand 5 in R2 group. It also has tertahydropyran group at R3 position and binds in hydrophobic pocket 2. Oxygen of tertahydropyran makes favorable hydrogen bonding interactions with Tyr215 and Gln98, and hydrophobic interactions of Tyr215, Pro66 and Val455 amino acid residues. R2 group binds toward hydrophobic pocket 3 and cyclopropyl group makes van der Waals packing with Met210 and Met235. This type of interaction is consistent with ligand 14 (class II GKA) interaction. Class II GKAs binding shows accommodation of bigger hydrophobic group in hydrophobic pocket 3. Ligand 18 is structurally different from all classes of ligand, it lacks amide group. This ligand shows same kind of hydrogen bond interactions with the Arg63 but hydrogen bonding partners are different. Similar kind of interaction with structurally different ligands ascertains that Arg63 is specifically involved in hydrogen bond formation with GKAs. One structural requirement of GKAs would be presence of adjacent hydrogen bond accepter and donor group. Ligand 19 and 20 are unique in having tri-substituted cyclopropyl ring. Substituents on cyclopropyl ring makes arms of the ligands and leave ligands less flexible as compared to class I GKAs. The docking studies of this class of ligands shows over 90% conformations in one cluster (Fig. 9

). The Oxygen of methylsulfonyl (SO2CH3) group forms hydrogen bond with Tyr215 and Gln98. All other interactions are similar to other members of this class. The binding energy improves over 2 kcal/mol because of the unique hydrophobic interaction with His218. Ligand 7 contains cyclopropyl group instead of benzyl group of ligand 5 in R2 group. It also has tertahydropyran group at R3 position and binds in hydrophobic pocket 2. Oxygen of tertahydropyran makes favorable hydrogen bonding interactions with Tyr215 and Gln98, and hydrophobic interactions of Tyr215, Pro66 and Val455 amino acid residues. R2 group binds toward hydrophobic pocket 3 and cyclopropyl group makes van der Waals packing with Met210 and Met235. This type of interaction is consistent with ligand 14 (class II GKA) interaction. Class II GKAs binding shows accommodation of bigger hydrophobic group in hydrophobic pocket 3. Ligand 18 is structurally different from all classes of ligand, it lacks amide group. This ligand shows same kind of hydrogen bond interactions with the Arg63 but hydrogen bonding partners are different. Similar kind of interaction with structurally different ligands ascertains that Arg63 is specifically involved in hydrogen bond formation with GKAs. One structural requirement of GKAs would be presence of adjacent hydrogen bond accepter and donor group. Ligand 19 and 20 are unique in having tri-substituted cyclopropyl ring. Substituents on cyclopropyl ring makes arms of the ligands and leave ligands less flexible as compared to class I GKAs. The docking studies of this class of ligands shows over 90% conformations in one cluster (Fig. 9 ). Ligand 22 resembles class I GKAs, the only difference is presence of sulfonyl group instead of carbonyl group. The replacement of carbonyl group with sulfonyl group does not change much binding interaction pattern with GK.

). Ligand 22 resembles class I GKAs, the only difference is presence of sulfonyl group instead of carbonyl group. The replacement of carbonyl group with sulfonyl group does not change much binding interaction pattern with GK.

Structure Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis

The docking studies gave better insight and understanding on how various allosteric GKAs interact with Glucokinase. This study acknowledges contribution of hydrophobic interactions as the most to the binding energies of these activators. Hydrophobic and aromatic nature of the R1/R2/R3 group is more favorable. Overall, Pocket 2 accommodates the most diverse groups which have aromatic, hydrophobic and even hydrophilic substituents. Try215 is the key residue involved in aromatic, hydrophobic and hydrogen bond forming interactions. Gln98 amino acid residue sometimes also involved in hydrogen bond formation in pocket 2. Ile211 and Leu451 are other hydrophobic residues contributing toward van der Waals packing in pocket 2. Continued exploration of Pocket 2 binding is much warranted for more optimal GKA design. Aromatic heterocycles and hydrogen bond forming linkers seem the choices to build the R2 arm of GKA. On the other hand, Pocket 3 is more solvent exposed and seems to have less potential for GKA optimization due to interaction/desolvation energy compensation. In conclusion, we demonstrate the interactions of GKAs at allosteric site at atomic level and the important interactions which could be helpful in design of novel glucokinase activator. These activators could be very efficient as blood glucose-lowering agents due to its dual mechanism of augmenting islet insulin release and enhancing hepatic glucose disposal. The binding interactions and involvement of specific amino acid could lead to design of novel glucokinase activator with higher selectivity and least side effects for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and related disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by an allocation of computing time from the Ohio Supercomputer Center.