- Home

- About Journals

-

Information for Authors/ReviewersEditorial Policies

Publication Fee

Publication Cycle - Process Flowchart

Online Manuscript Submission and Tracking System

Publishing Ethics and Rectitude

Authorship

Author Benefits

Reviewer Guidelines

Guest Editor Guidelines

Peer Review Workflow

Quick Track Option

Copyediting Services

Bentham Open Membership

Bentham Open Advisory Board

Archiving Policies

Fabricating and Stating False Information

Post Publication Discussions and Corrections

Editorial Management

Advertise With Us

Funding Agencies

Rate List

Kudos

General FAQs

Special Fee Waivers and Discounts

- Contact

- Help

- About Us

- Search

Open Urban Studies and Demography Journal

(Discontinued)

ISSN: 2352-6319 ― Volume 4, 2018

Restless Space Narratives of Change Around Landscapes of Rupture

Christiane Sörensen*, Wiltrud Simbürger

Abstract

For a project cooperation in landscape architecture, supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), we looked at small strips of urban land in Germany and Israel that carry the marks of a violent political rupture. Two areas symptomatic of this condition in the cities of Berlin and Jerusalem were studied in terms of their disciplinary, social, and political changes: an area around the former Luisenstädtischer Kanal which was part of the Berlin wall and the Musrara neighborhood in Jerusalem where the pre1967 border to Jordan ran through. The first goal was to lay bare the narratives embedded in these sites and analyse the interventions that had created them. In a second step, the attempts of healing the topographical wounds left after the disappearance of the political border were studied. While in Jerusalem the measures taken were mainly infrastructural - a highway and a light rail track were built acting again as barriers - , the Berlin site became remade through a grinding process of give-and-take between different stakeholders. This paper presents the first results of the study about the Berlin area.

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2015Volume: 1

Issue: Suppl 1-M9

First Page: 84

Last Page: 90

Publisher Id: OUSDJ-1-84

DOI: 10.2174/2352631901401010084

Article History:

Received Date: 10/6/2015Revision Received Date: 15/6/2015

Acceptance Date: 15/6/2015

Electronic publication date: 31/12/2015

Collection year: 2015

open-access license: This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC 4.0) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode), which permits unrestricted, non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the work is properly cited.

* Address correspondence to this author at the Landscape Architecture, HafenCity Universität Hamburg, Überseeallee 16, D-20457 Hamburg, Germany; Tel: ++49-(0)40-42827-4398; E-mail: christiane.soerensen@hcu-hamburg.de

| Open Peer Review Details | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Manuscript submitted on 10-6-2015 |

Original Manuscript | Restless Space Narratives of Change Around Landscapes of Rupture | |

INTRODUCTION

Recent events have brought a specific kind of border back into focus: small strips of urban land that carry the marks of a violent political rupture. The 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin wall recalled the line that haunted the city between 1961-1990 in the same way as the bombing of a Jerusalem synagogue by Israeli Arabs brought back the former no man‘s land dividing Jerusalem‘s city proper. Both strips suppressed the free flow of movement within the cities for decades. Two areas symptomatic of this condition of rupture in Berlin and Jerusalem were identified and investigated in terms of their political, social, and disciplinary changes. One area is located around the former Luisenstädtischer Kanal which was part of the Berlin wall, the other is the Musrara neighborhood in Jerusalem where the pre1967 border to Jordan ran through. Our first goal was to lay bare the narratives embedded in the topography of these sites and analyze the interventions that created them. We then looked at the attempts of healing the topographical wounds left after the disappearance of the political border. While in Jerusalem the measures taken were mainly infrastructural - a highway and a light rail track were built acting again as barriers - , the Berlin site became remade through a grinding process of give-and-take between different stakeholders. In this paper we present the first results of the Berlin study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Berlin site was investigated using an integrative approach of diverse spatial practices, relying on both analytical and design research techniques. This method of “topographical thinking and designing” [1Sörensen C. Topographical thinking and designing. In: Fischer H, Ozacky-Lazar S, Wolschke-Bulmahn J, Eds. Environmental policy and landscape architecture. München: Avm-edition 2014; pp. 153-62.] takes an initial cue from Andre Corboz' notion of the palimpsest [2Corboz A. Die Kunst, Stadt und Land zum Sprechen zu bringen. Basel, Boston. Berlin: Birkhäuser 2001; pp. 143-65.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783035602654] ] which conceives of territory as being inscribed, erased and re-inscribed by its inhabitants through time, with remnants of former inscriptions legible in contemporary space. In a critique of Corboz's concept, cultural geographers Stephen Daniels and Denis Cosgrove have proposed the notion of the “flickering text” of a word-processor alluding to the inherent unreliability of the process of deciphering [3Cosgrove D, Daniels S, Eds. The iconography of landscape. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1988.]. “Narrative” has thus become a crucial word for us as it takes into account Daniels' and Cosgrove's point without compromising the basics of Corboz' concept. We specifically rely on previous theoretical work about landscape narratives by Matthew Potteiger and Jamie Purinton [4Historical maps of Berlin were obtained through the open data

portal of the Berlin Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und

Umwelt http://fbinterstadt-berlinde/fb/indexjsp The maps shown

in this paper have been altered by the authors ] and its implementation for example by Tal Alon-Mozes in [5Potteiger M, Purinton J. Landscape narratives, design practices for telling stories. New York: Wiley 1998., 6Alon-Mozes T, Maya M. Zippori National park as a composite narrative. Isr Stud 2015; 20(1): 1-30.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.2979/israelstudies.20.1.1] ].

The method of topographical thinking and designing aims to bring earlier narratives of a site to the fore, interpret their meaning on a disciplinary, historical, and social level and make sense of the complex interrelations present in the contemporary space. To this effect, we traced the topographical changes caused by man-made interventions through an analysis of historical maps [7Alon-Mozes T. Environmental narratives and the Israeli agricultural landscape. In: Martinho da Silva I, Portela MT, Andrade G, Eds. Proceedings of the ECLAS Conference Porto. 2014 Sept 21-23; Porto, Portugal: School of Science, University of Porto 2014; pp. 71-5.] and developed a disciplinary analysis of the formal elements of the interventions within the framework of a design studio. The emerging narratives were thickened by additional historical research which was specifically focused on the political intentions and mindsets underlying the interventions. The concept of a braid of narratives was instrumental in providing a framework for describing the meandering web of relations of the space in question. While we present the narratives mostly in a disentangled fashion, the braid reminds of their complex interrelationships.

The City Planner’s Narrative: Making Infrastructure

Corboz‘s notion of the palimpsest immediately comes to mind when one starts to study the history of Berlin Luisenstadt and the Luisenstädtischer Kanal (Fig. 1 ). Now a thin strip of open space amidst the urban density of the districts Mitte and Kreuzberg, it has been a product of perpetual writing, erasure and rewriting of landscape. In the beginning, the narratives were spurred by grand urban planning visions, later by social, political and preservationist considerations. Specifically after the fall of the wall, they emerged through contention between different stakeholders [8 A range of literature was used to build an account of the canal's

history First and foremost, Klaus Duntze's excellent and lively

written history provided a comprehensive overview (Duntze K Der

Luisenstädtische Kanal Berlin: Berlin Story, 2011) For information

about city planner Peter Joseph Lenné see for example Buttlar

F (Eds) Peter Joseph Lenné-Volkspark und Arkadien Berlin:

Nicolai, 1989; Günther H Peter Joseph Lenné: Gärten / Parke /

Landschaften Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1985; Schönemann

H (Eds) Peter Joseph Lenné: Katalog der Zeichnungen Tübingen:

Ernst Wasmuth Verlag,1993; Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung

und Umweltschutz, Referat Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Gartendenkmalpflege

Heft 5: Bestandskatalog der Berliner Pläne von

Peter Joseph Lenné Berlin, 1990 To learn more about Erwin

Barth, see Land D, Wenzel J Heimat, Natur und Weltstadt: Leben

und Werk des Gartenarchitekten Erwin Barth Leipzig: Koehler &

Amelang 2005 General information about Berlin's urban development

and historic preservation efforts can be found in Schwenk H

Berliner Stadtentwicklung von A bis Z: Kleines Handbuch zum

Werden und Wachsen der deutschen Hauptstadt Berlin: Luisenstädtischer

Bildungsverein eV 1998; Landesdenkmalamt Berlin

(Eds) Gartenkunst Berlin- 20 Jahre Gartendenkmalpflege in der

Metropole Berlin: Schelzky&Jeep 1999 2011.].

). Now a thin strip of open space amidst the urban density of the districts Mitte and Kreuzberg, it has been a product of perpetual writing, erasure and rewriting of landscape. In the beginning, the narratives were spurred by grand urban planning visions, later by social, political and preservationist considerations. Specifically after the fall of the wall, they emerged through contention between different stakeholders [8 A range of literature was used to build an account of the canal's

history First and foremost, Klaus Duntze's excellent and lively

written history provided a comprehensive overview (Duntze K Der

Luisenstädtische Kanal Berlin: Berlin Story, 2011) For information

about city planner Peter Joseph Lenné see for example Buttlar

F (Eds) Peter Joseph Lenné-Volkspark und Arkadien Berlin:

Nicolai, 1989; Günther H Peter Joseph Lenné: Gärten / Parke /

Landschaften Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1985; Schönemann

H (Eds) Peter Joseph Lenné: Katalog der Zeichnungen Tübingen:

Ernst Wasmuth Verlag,1993; Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung

und Umweltschutz, Referat Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Gartendenkmalpflege

Heft 5: Bestandskatalog der Berliner Pläne von

Peter Joseph Lenné Berlin, 1990 To learn more about Erwin

Barth, see Land D, Wenzel J Heimat, Natur und Weltstadt: Leben

und Werk des Gartenarchitekten Erwin Barth Leipzig: Koehler &

Amelang 2005 General information about Berlin's urban development

and historic preservation efforts can be found in Schwenk H

Berliner Stadtentwicklung von A bis Z: Kleines Handbuch zum

Werden und Wachsen der deutschen Hauptstadt Berlin: Luisenstädtischer

Bildungsverein eV 1998; Landesdenkmalamt Berlin

(Eds) Gartenkunst Berlin- 20 Jahre Gartendenkmalpflege in der

Metropole Berlin: Schelzky&Jeep 1999 2011.].

|

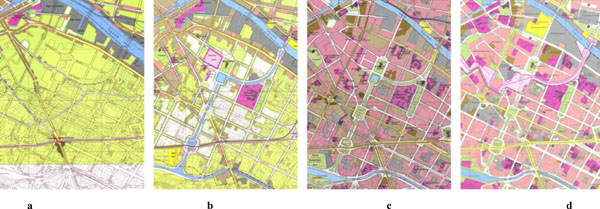

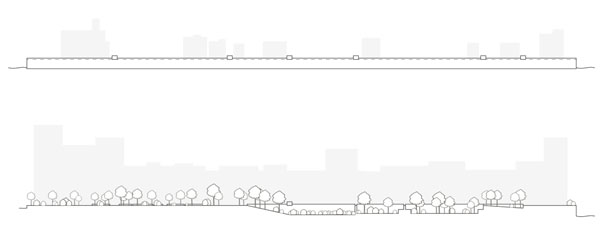

Fig. (1) Luisenstädtischer Kanal, 2014. 1 – Spree. 2 - St. Thomas. 3 - St. Michael. 4 – Engelbecken. 5 – Oranienplatz. 6 – Wassertorplatz. 7 - Landwehr-Kanal. |

|

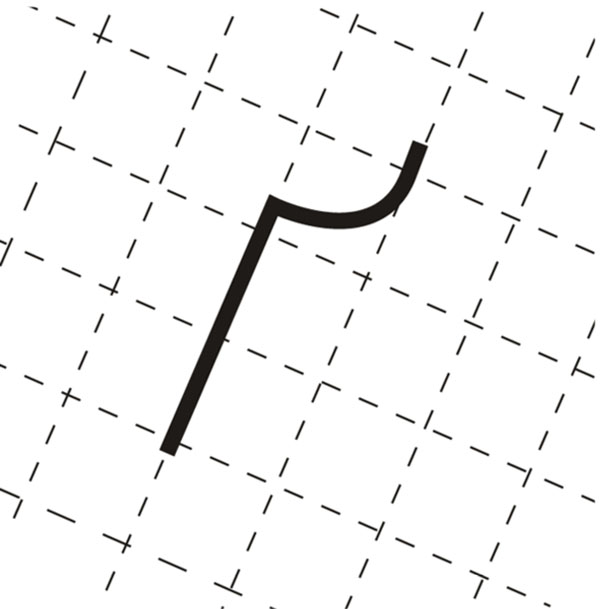

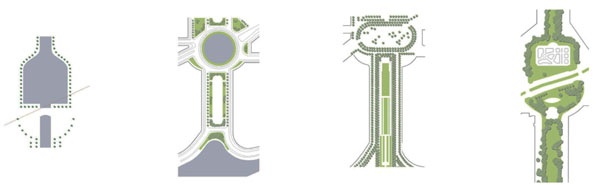

Fig. (3) The hook: The original design decision idea is still visible as a succinct formal element within the urban grid of today. |

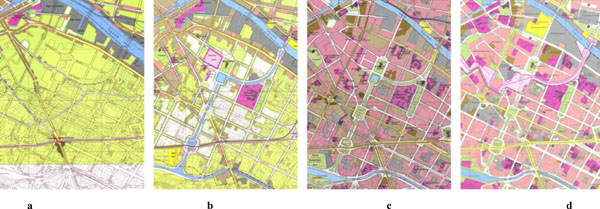

|

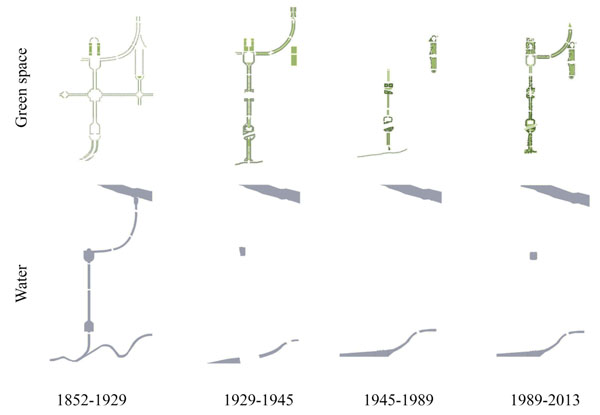

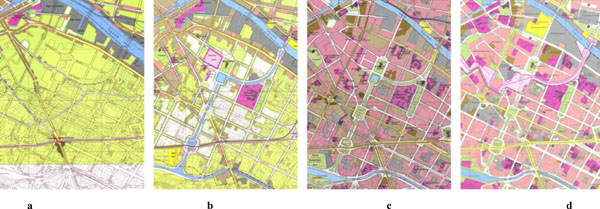

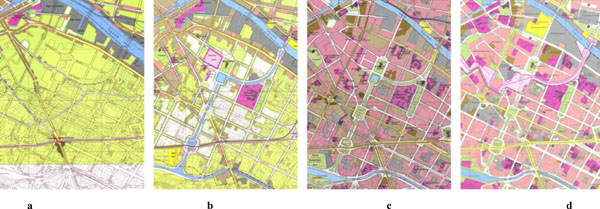

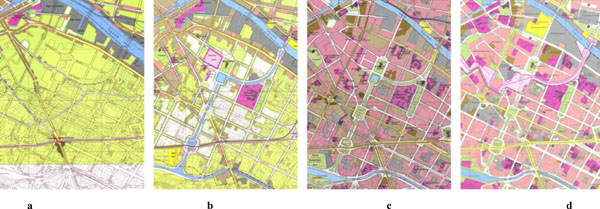

Fig. (4) The development of green spaces and water features in the area from 1852 to 2013. |

|

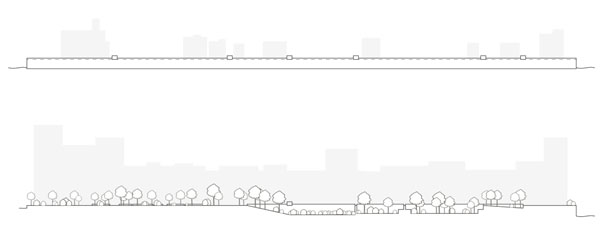

Fig. (5) Erwin Barth's 1929 plan to create sunken gardens is still legible today. |

|

Fig. (6) Luisenstadt ruptured in two, 1961-1989. |

|

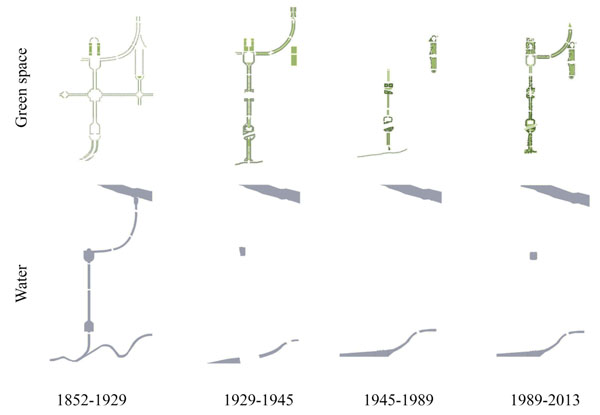

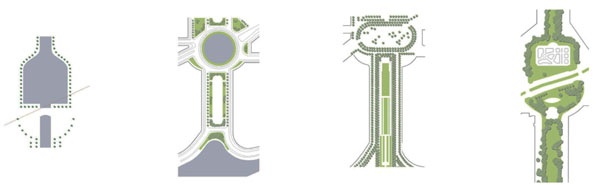

Fig. (7) Development of the Wassertorplatz: On the far right, the shift towards the natural, organic design can be detected. |

The historic neighborhood of Luisenstadt was one of the early and major extension in the East of Berlin‘s old inner city in the first decades of the 19th century (Fig. 2a ).

).

Commissioned by king Friedrich Wilhelm IV, city planner and landscape architect Peter Joseph Lenné [9 Lenné was also in charge of the Berlin Tiergarten and the Gardens

of Sanssouci at Potsdam Buttlar F, Eds Peter Joseph Lenné-

Volkspark und Arkadien, Berlin: Nicolai, 1989 1989.] proposed a classical plan consisting of a geometrical grid of orthogonal streets for the new development at the so-called Köpenicker Feld (Fig. 2b ). In order to provide access to the area, a canal was proposed to connect the River Spree in the North and the Landwehrkanal in the South. Lenné's first designs showed the canal as a straight line in the middle of an orthogonal grid.

). In order to provide access to the area, a canal was proposed to connect the River Spree in the North and the Landwehrkanal in the South. Lenné's first designs showed the canal as a straight line in the middle of an orthogonal grid.

The unusual shape the canal eventually took on – a “hook” consisting of a straight line with a quarter circle at the Northern end – originated from a sketch by Friedrich Wilhelm IV who was heavily involved in the planning process [10 Luisenstadt was named after the king's mother, Queen Luise Duntze K Der Luisenstädtische Kanal: Berlin Story 2011 2011.]. By adding the circle to the line the king already anticipated the building of the church St. Michael at the bend near the Spree. The canal was to be not merely a means of infrastructure, but also one of aesthetic experience. Built as a hook, it provided an uninterrupted view between the Landwehr-Kanal and the soon to be built church [11Duntze K. Duntze K Der Luisenstädtische Kanal: Berlin Story, 2011; p 12 . 2011.]. The visual experience of this strong axis was amplified by a number of classically designed squares, basins and a continuous row of linden trees which opened up additional vistas into the districts. Until today, the hook of the Luisenstädtischer Kanal acts a strong formal element within the Berlin cityscape (Figs. 1 and 3).

Completed in 1852, the canal proved to be vital for the transportation of building material to the area in its early years. Movement on the canal was mainly related to construction and commerce. The success, though, did not last for long. Since the slope of the canal was too little and thus the water flow too slow, the canal began to silt up. Citizens began to complain about unpleasant smells; sanitary concerns were raised. The canal came to be seen as a source for attracting mosquitos and hence a carrier of diseases. So, when in the 1920s a decision was made to build a subway connection between Kottbuser Tor and Alexanderplatz, the canal fell victim to the new infrastructural challenges. In 1928, work started to fill up the canal and turn it into a series of green spaces.

The Garden Historian’s Narrative: Transformation and Memory

With the fate of the canal as infrastructural element sealed, the filled-up space became rewritten as an area for recreation. In 1929, horticultural director Erwin Barth proposed a sequence of gardens which were alternately geared towards leisure, horticultural education and the decorative (Fig. 4 ). His plan, though, was not intended to completely erase the canal‘s utilitarian past. The new areas were designed as sunken gardens 1,6 meters beneath street level, thus keeping the memory of a time alive when the green surface one was presently strolling on was made of water (Fig. 5

). His plan, though, was not intended to completely erase the canal‘s utilitarian past. The new areas were designed as sunken gardens 1,6 meters beneath street level, thus keeping the memory of a time alive when the green surface one was presently strolling on was made of water (Fig. 5 ). In addition, Barth left the basin of the Engelbecken which is situated in front of St. Michael in place and transformed it into a fish pond (or an ice rink in winter times.) Barth‘s plan was deliberately translucent to enable a reading of the canal‘s past through its present use. Though not all of his ideas were implemented, his basic approach became reality: The busy flow of commercial transport gave way to the leisurely stroll (Fig. 2c

). In addition, Barth left the basin of the Engelbecken which is situated in front of St. Michael in place and transformed it into a fish pond (or an ice rink in winter times.) Barth‘s plan was deliberately translucent to enable a reading of the canal‘s past through its present use. Though not all of his ideas were implemented, his basic approach became reality: The busy flow of commercial transport gave way to the leisurely stroll (Fig. 2c ).

).

The Political Narrative: Obliteration

In 1945, at the end of WWII, the northern and western parts of the Luisenstadt were destroyed during heavy bombardment. Parts of the sunken gardens were later filled with rubble and wreckage from destroyed buildings which resulted in further eradicating the utilitarian aspect of the space‘s past. Then in 1961, the political division of the city which became established after the war was literally set in stone (Fig. 2d ). The Berlin Wall was built and became the most notorious spatial expression for the political rupture marking the city of Berlin in particular and Europe as a whole. The land around the former Luisenstädtischer Kanal became part of a narrative of forced standstill and obliteration. Following the Spree from the East, the rupture line continued along the Friedrich Wilhelm’s signature loop to the Engelbecken before it proceeded further West. St. Michael was now part of East Berlin. Even today, the man-made topography of the former canal serves again as political border: It represents the administrative separation line between the districts of Mitte and Kreuzberg.

). The Berlin Wall was built and became the most notorious spatial expression for the political rupture marking the city of Berlin in particular and Europe as a whole. The land around the former Luisenstädtischer Kanal became part of a narrative of forced standstill and obliteration. Following the Spree from the East, the rupture line continued along the Friedrich Wilhelm’s signature loop to the Engelbecken before it proceeded further West. St. Michael was now part of East Berlin. Even today, the man-made topography of the former canal serves again as political border: It represents the administrative separation line between the districts of Mitte and Kreuzberg.

The open spaces in the Eastern and Western part of the city embarked on different trajectories. The Eastern area of the canal was completely filled-up and leveled, the linden trees were chopped down. The Engelbecken which was equally filled up with waste from nearby demolished houses became part of the border zone itself, - a sandy empty strip of land which ordinary citizens were prohibited to approach or enter. Memories of the site‘s previous lives, its infrastructural past, Lenné’s classical garden design, or Barth‘s sunken gardens, were obliterated. The sole memento left was its initial form, the hook. The site resembled a tabula rasa, but only on first glance. A new message about the unsurmountable barrier between two political systems became inscribed in space. And any attempt of rewriting it was threatened to be met with force (Fig. 6 ).

).

The Citizen’s Narrative: Participation

While the Eastern part was transformed into a lethal wasteland, the trajectory of the Western part of the Luisenstädtischer Kanal took a different turn: It became a theater for the struggle between neighborhood activists and city authorities. After years of failed top-down city planning and attempts to build a “new” city from the rubble without resident input, discontent and resistance in the neighborhoods grew. The strategies of municipal housing associations to deliberately leave apartment buildings vacant to decay led to squatting. Areas along the border strip attracted informal settlements (Wagenburgen) and alternative lifestyles. Citizens started to organize, demanding for their voices to be heard. As a remedial measure, the municipality of Kreuzberg developed special strategies for the revitalization of the Luisenstadt with a strong emphasis on public participation in the planning processes. The International Building Exhibition (IBA) 1984 became an important planning instrument during this time. One of its themes, Critical Reconstruction, focused

on the sensitive reconstruction of Kreuzberg as lively and livable neighbourhood. The impact of the bottom-up movement on design decisions for the Luisenstädtischer Kanal was considerable. Public sentiment supported approaches that broke with tradition (and thereby repudiated Germany’s recent past). Lenné’s classical concepts as well as Barth’s sunken gardens were rejected in favor of a new design philosophy featuring organic, naturally appearing forms. In architect Hinrich Baller’s redesign of the southern parts of the canal at the Wassertorplatz, the former straight lines and geometric shapes were transformed into hilly and lush park (Fig. 7 ). A delicate garden bridge was the only element evocative of the site’s former past.

). A delicate garden bridge was the only element evocative of the site’s former past.

The Garden Historian’s and the Citizen’s Narrative (Intertwined): Divergent Strategies of Healing

Right after the fall of the wall in 1990, for the first time in its history as an open space, the former border zone became undefined ground. No official function was attached to it anymore, and for a short period, the wasteland developed a narrative out of its own. Its use by residents was random and temporal, governed by instantaneous needs and desires: play, strolls, or dogwalks. For a short moment in time, the ground was up in the air, with its latent possibilities in limbo.

The lack of definition invited a disparate lot of groups to stake their claims. The municipal authority for the preservation of historical gardens hoped to revive the disciplinary heritage of Lenné and Barth, while traffic planners dreamed of a new highway. In order to pre-empt the transformation of the area into a major thoroughfare, preservationists replanted Lenné‘s linden trees in 1991.

For the next decades, similar disputes were fought out by stakeholders with different agendas along different value systems and time frames. While the city’s preservationists favored a disciplinary approach and would have sacrificed some trees in order to recreate a moment in Lenné’s and Barth‘s time, a group of nature conservationists was willing to forgo preservation funds to save trees. Barth’s sunken garden had no value within their agenda; trees had. Another group feared that gentrification - now that the once marginalized district was a desirable location in the center of the city - would destroy the specific urban character of the Kreuzberg district. Their zero hour of design philosophy was set in the 80s around the struggle about Baller’s organic Wassertorplatz design when this special Kreuzberg identity came into being. Earlier memories were being ignored by this group.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Even though there was an overall consensus about bringing the Eastern and the Western part of the area together (both in terms of population and topography), views on appropriate strategies diverged greatly. What was a socio-political issue for one side, was a disciplinary issue or an environmental one for the other. Each group won the day at some point during the decade-long process, making the restoration of the green corridor a work of discontinuity. In the end, some of the gardens were reconstructed after Barth’s historic plans and at most places the original level of the sunken gardens was restored. The promenades at the Engelbecken were rebuilt. At the same time, other parts resumed the natural form language of the 1980s. Today the area around the former canal consists of a heterogenic sequence of open spaces of different characters and origins. Although it still represents a strong formal element in the urban density of Berlin, it is not readable as a continuous object anymore. Since an agreement for an overall solution could not be achieved, the envisioned green corridor remained a “torso” [12Duntze K. Duntze K Der Luisenstädtische Kanal: Berlin Story, 2011; p 364 . 2011.].

It seems ironic that the memory of a rupture still lingers over the site, now being expressed by the friction between the different attempts to redefine its identity. The big rupture was mended by a series of smaller ones. While the former political fragmentation of the area was the result of a top-down decision, now that the entire area was again available for rewriting, the democratic power struggles between different stakeholders resulted again in fragmentation, albeit on a much lower level.

CONCLUSION

Originally conceived as an infrastructural element, the Luisenstädtischer Kanal had a clear identity as a means of transport and barrier. Topographically, the water element acted as a divider of space. Thus it directed the flow of movement, enabling a certain kinds while prohibiting others. The element conceived and implemented during the political system of a monarchy reflected unity in terms of use and form.

Erwin Barth's design replaced water with gardens, connecting the originally divided spaces and encouraging the slow flow of leisurely movement. At the same time the trace of a barrier was still present. The former dividing element now acted as a seam that was intentionally left visible. Another division – this time the result of a clash between political power structures – followed during the time of Germany's division. The area experienced a topographical rupture that was prompted by its partly rewriting into an inaccessible border zone. But still, as it was in Lenne's and Barth's time, the identity of the space, though now divided in two, was clearly defined.

The following devaluation of the space adjacent to the border, though, opened it up for experiments. It invited acts of unofficial ad hoc appropriation by residents which fostered the development of a strong grass roots culture in the area. This movement was later reflected in the intense process of citizen participation implemented by the IBA during the 1980s and in the restoration discussions after the fall of the wall.

Since after 1990 the aims of city administrators, preservationists and environmentalists rarely overlapped, the result was a hard fought compromise that is reflected in the heterogenic “checkered” topography of the space. Instead of implementing an all-encompassing, unified design vision, the site became a strong testament to the diversity of its stakeholders’ smaller visions. The chosen approach to close a topographical wound was one of contestation and negotiation “Checkeredness” became its mode of healing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Iris Aravot at the Technion in Haifa, Israel, Gero Heck at relais Landschaftsarchitekten, Berlin, Karoline Liedtke at Cobe Architects Copenhagen, and the students of the design studio Luisenstädtischer Kanal at the HafenCity University, Hamburg, for their contributions. Additional thanks go to the German Research Foundation (DFG) for its financial support.

REFERENCES

| [1] | Sörensen C. Topographical thinking and designing. In: Fischer H, Ozacky-Lazar S, Wolschke-Bulmahn J, Eds. Environmental policy and landscape architecture. München: Avm-edition 2014; pp. 153-62. |

| [2] | Corboz A. Die Kunst, Stadt und Land zum Sprechen zu bringen. Basel, Boston. Berlin: Birkhäuser 2001; pp. 143-65. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783035602654] |

| [3] | Cosgrove D, Daniels S, Eds. The iconography of landscape. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1988. |

| [4] | Historical maps of Berlin were obtained through the open data portal of the Berlin Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt http://fbinterstadt-berlinde/fb/indexjsp The maps shown in this paper have been altered by the authors |

| [5] | Potteiger M, Purinton J. Landscape narratives, design practices for telling stories. New York: Wiley 1998. |

| [6] | Alon-Mozes T, Maya M. Zippori National park as a composite narrative. Isr Stud 2015; 20(1): 1-30. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2979/israelstudies.20.1.1] |

| [7] | Alon-Mozes T. Environmental narratives and the Israeli agricultural landscape. In: Martinho da Silva I, Portela MT, Andrade G, Eds. Proceedings of the ECLAS Conference Porto. 2014 Sept 21-23; Porto, Portugal: School of Science, University of Porto 2014; pp. 71-5. |

| [8] | A range of literature was used to build an account of the canal's history First and foremost, Klaus Duntze's excellent and lively written history provided a comprehensive overview (Duntze K Der Luisenstädtische Kanal Berlin: Berlin Story, 2011) For information about city planner Peter Joseph Lenné see for example Buttlar F (Eds) Peter Joseph Lenné-Volkspark und Arkadien Berlin: Nicolai, 1989; Günther H Peter Joseph Lenné: Gärten / Parke / Landschaften Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1985; Schönemann H (Eds) Peter Joseph Lenné: Katalog der Zeichnungen Tübingen: Ernst Wasmuth Verlag,1993; Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umweltschutz, Referat Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Gartendenkmalpflege Heft 5: Bestandskatalog der Berliner Pläne von Peter Joseph Lenné Berlin, 1990 To learn more about Erwin Barth, see Land D, Wenzel J Heimat, Natur und Weltstadt: Leben und Werk des Gartenarchitekten Erwin Barth Leipzig: Koehler & Amelang 2005 General information about Berlin's urban development and historic preservation efforts can be found in Schwenk H Berliner Stadtentwicklung von A bis Z: Kleines Handbuch zum Werden und Wachsen der deutschen Hauptstadt Berlin: Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein eV 1998; Landesdenkmalamt Berlin (Eds) Gartenkunst Berlin- 20 Jahre Gartendenkmalpflege in der Metropole Berlin: Schelzky&Jeep 1999 2011. |

| [9] | Lenné was also in charge of the Berlin Tiergarten and the Gardens of Sanssouci at Potsdam Buttlar F, Eds Peter Joseph Lenné- Volkspark und Arkadien, Berlin: Nicolai, 1989 1989. |

| [10] | Luisenstadt was named after the king's mother, Queen Luise Duntze K Der Luisenstädtische Kanal: Berlin Story 2011 2011. |

| [11] | Duntze K. Duntze K Der Luisenstädtische Kanal: Berlin Story, 2011; p 12 . 2011. |

| [12] | Duntze K. Duntze K Der Luisenstädtische Kanal: Berlin Story, 2011; p 364 . 2011. |