- Home

- About Journals

-

Information for Authors/ReviewersEditorial Policies

Publication Fee

Publication Cycle - Process Flowchart

Online Manuscript Submission and Tracking System

Publishing Ethics and Rectitude

Authorship

Author Benefits

Reviewer Guidelines

Guest Editor Guidelines

Peer Review Workflow

Quick Track Option

Copyediting Services

Bentham Open Membership

Bentham Open Advisory Board

Archiving Policies

Fabricating and Stating False Information

Post Publication Discussions and Corrections

Editorial Management

Advertise With Us

Funding Agencies

Rate List

Kudos

General FAQs

Special Fee Waivers and Discounts

- Contact

- Help

- About Us

- Search

The Open Virology Journal

(Discontinued)

ISSN: 1874-3579 ― Volume 15, 2021

Detection of Human Polyomavirus DNA Using the Genome Profiling Method

Yuka Tanaka, Rieko Hirata, Kyohei Mashita, Stuart Mclean, Hiroshi Ikegaya*

Abstract

Background

In the field of forensic medicine, it is very difficult to know prior to autopsy what kind of virus has infected a body.

Objective

We assessed the potential of the genome profiling (GP) method, which was developed in the field of bioengineering, to identify viruses belonging to one species.

Method

Two species in the same family, JC and BK viruses, were used in this study. Using plasmid samples, we compared the findings of molecular phylogenetic analysis using conventional genome sequencing with the results of cluster analysis using the random PCR-based GP method and discussed whether the GP method can be used to determine viral species.

Results

It was possible to distinguish these two different viral species. In addition to this, in our trial we could also detect the JC virus from a clinical sample.

Conclusion

This method does not require special reagent sets for each viral species. Though our findings are still in the trial period, the GP method may be a simple, easy, and economical tool to detect viral species in the near future.

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2015Volume: 9

First Page: 29

Last Page: 37

Publisher Id: TOVJ-9-29

DOI: 10.2174/1874357901509010029

Article History:

Received Date: 24/6/2015Revision Received Date: 28/10/2015

Acceptance Date: 28/10/2015

Electronic publication date: 24/11/2015

Collection year: 2015

open-access license: This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), which permits unrestricted, noncommercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the work is properly cited.

* Address correspondence to this author at the Department of Forensic Medicine, Graduate School of Medical Science, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine 465 Kajiicho, Kamigyo, Kyoto 602-8566, Japan; E-mails: ikegaya-tky@umin.ac.jp, ikegaya@koto.kpu-m.ac.jp

| Open Peer Review Details | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Manuscript submitted on 24-6-2015 |

Original Manuscript | Detection of Human Polyomavirus DNA Using the Genome Profiling Method | |

1. INTRODUCTION

The genome profiling (GP) method, which was developed in the field of bioengineering in 2000 by Nishigaki et al. [1Nishigaki K, Naimuddin M, Hamano K. Genome profiling: a realistic solution for genotype-based identification of species J Biochem 2000; 128(1): 107-12.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022719] [PMID: 10876164] ] can be used to distinguish differences between genomes using a random PCR approach and temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1 ). In the field of virology, sequencing and phylogenetic analyses are usually employed to analyze viral genomes. However, these approaches require considerable effort, expensive equipment, and specific reagents. Conversely, the GP method is reportedly a very simple tool to analyze whole genomes and requires inexpensive equipment and versatile reagents [2Suwa N, Ikegaya H, Takasaka T, Nishigaki K, Sakurada K. Human blood identification using the genome profiling method Leg Med (Tokyo) 2012; 14(3): 121-5.

). In the field of virology, sequencing and phylogenetic analyses are usually employed to analyze viral genomes. However, these approaches require considerable effort, expensive equipment, and specific reagents. Conversely, the GP method is reportedly a very simple tool to analyze whole genomes and requires inexpensive equipment and versatile reagents [2Suwa N, Ikegaya H, Takasaka T, Nishigaki K, Sakurada K. Human blood identification using the genome profiling method Leg Med (Tokyo) 2012; 14(3): 121-5.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2012.01.001] [PMID: 22285643] ].

|

Fig. (1) Temperature gradient gel electrophoresis apparatus (µTG; TAITEC, Saitama, Japan). |

|

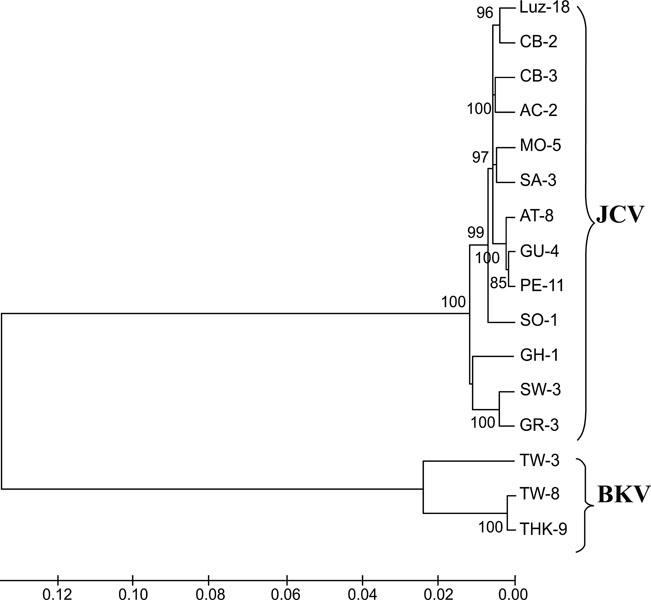

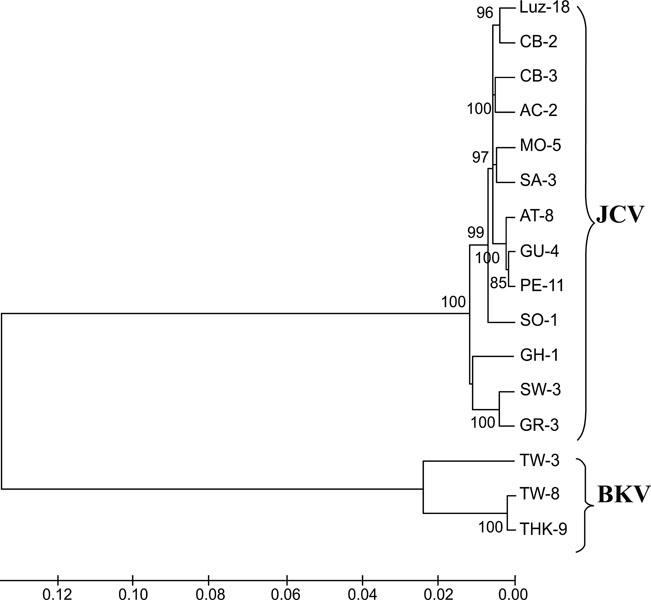

Fig. (5)

Phylogenetic analysis of JCPyV and BKPyV

whole genomes. NJ phylogenetic tree showing the relationship between the JCPyV

and BKPyV isolates. The numbers at the nodes indicate the bootstrap confidence

levels (percent) obtained with 1,000 replicates [40Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap Evolution 1985; 39: 783-91. |

The first step of the GP method consists of PCR using random primers, which amplifies the whole genome partially and randomly. This process is considered almost the same as random sampling from the whole genome. Therefore, analysis of the randomly generated PCR fragments represents whole genome information. In the second step of the GP method, the amplified DNA fragments are electrophoresed in a temperature gradient polyacrylamide gel. With this gel, sequence-specific temperature denaturation points are obtained. We call these points “species identification dots” (spiddos). By analyzing these spiddos with standards, similar genome samples are recognized as a single cluster.

The GP method has been used to distinguish mammalian species [2Suwa N, Ikegaya H, Takasaka T, Nishigaki K, Sakurada K. Human blood identification using the genome profiling method Leg Med (Tokyo) 2012; 14(3): 121-5.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2012.01.001] [PMID: 22285643] ] and human body fluid types [3Hirata R, Takasaka T, Miyamori D, et al. Use of the profiling method for the identification of saliva and sweat samples Jap J Forensic Sci Tech 2013; 18(1): 79-83.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.3408/jafst.18.79] , 4Takasaka T, Sakurada K, Akutsu T, Nishigaki K, Ikegaya H. Trials of the detection of semen and vaginal fluid RNA using the genome profiling method Leg Med (Tokyo) 2011; 13(5): 265-7.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2011.05.001] [PMID: 21684187] ] in the field of forensic medicine. However, it has not been used to distinguish species of virus. In forensic medicine, we usually examine cadavers with unknown histories. Therefore, for the protection of pathologists and other people who deal with the body, it is very important to know what infectious microbes they may carry. Recently there have been outbreaks of many newly emerging infectious diseases, including the Ebola virus, SARS virus, MEARS virus, avian influenza and so on. However, it is not easy to detect those viruses without special equipment and reagents.

In the present study, we assessed the potential of the GP method to identify viral species, using the JC virus (JCPyV) and BK virus (BKPyV) as representative microbes. These viruses belong to the polyomaviridae family, which consists of 5200 base-pair (bp) double-stranded DNA viruses [5Raj GV, Khalili K. Transcriptional regulation: lessons from the human neurotropic polyomavirus, JCV Virology 1995; 213(2): 283-91.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/viro.1995.0001] [PMID: 7491753] , 6Seif I, Khoury G, Dhar R. The genome of human papovavirus BKV Cell 1979; 18(4): 963-77.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(79)90209-5] [PMID: 229976] ]. We considered that it would be very easy to compare the conventional identification method with the GP method using these viruses as they have a relatively small genome and are DNA viruses, making it easy to analyze whole genomes by both methods.

JCPyV was first isolated from the brain of a patient with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in 1971 by Padgett et al. [7Padgett BL, Walker DL. New human papovaviruses Prog Med Virol 1976; 22: 1-35.

[PMID: 62371] ]. Recently, PML has become an important disease in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection [8Khalili K, Gordon J, White MK. The polyomavirus, JCV and its involvement in human disease Adv Exp Med Biol 2006; 577: 274-87.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/0-387-32957-9_20] [PMID: 16626043] ]. Previous studies showed that JCPyV infection is ubiquitous in humans [9Taguchi F, Kajioka J, Miyamura T. Prevalence rate and age of acquisition of antibodies against JC virus and BK virus in human sera Microbiol Immunol 1982; 26(11): 1057-64.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1348-0421.1982.tb00254.x] [PMID: 6300615] , 10Kitamura T, Aso Y, Kuniyoshi N, Hara K, Yogo Y. High incidence of urinary JC virus excretion in nonimmunosuppressed older patients J Infect Dis 1990; 161(6): 1128-33.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/infdis/161.6.1128] [PMID: 2161040] ]. After the initial infection, JCPyV persists in the kidney. It is detectable in the urine of 20–70% of healthy individuals, and its infection rate increases with age [10Kitamura T, Aso Y, Kuniyoshi N, Hara K, Yogo Y. High incidence of urinary JC virus excretion in nonimmunosuppressed older patients J Infect Dis 1990; 161(6): 1128-33.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/infdis/161.6.1128] [PMID: 2161040] -13Suzuki M, Zheng HY, Takasaka T, et al. Asian genotypes of JC virus in Japanese-Americans suggest familial transmission J Virol 2002; 76(19): 10074-8.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.76.19.10074-10078.2002] [PMID: 12208989] ].

BKPyV was isolated in 1971 from the urine of a renal transplantation patient [14Gardner SD, Field AM, Coleman DV, Hulme B. New human papovavirus (B.K.) isolated from urine after renal transplantation Lancet 1971; 1(7712): 1253-7.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(71)91776-4] [PMID: 4104714] ]. In bone marrow transplant patients, BKPyV induces hemorrhagic cystitis [15Giraud G, Bogdanovic G, Priftakis P, et al. The incidence of hemorrhagic cystitis and BK-viruria in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell recipients according to intensity of the conditioning regimen Haematologica 2006; 91(3): 401-4.

[PMID: 16531266] ]. BKPyV infection is also ubiquitous in humans and detectable in the urine of healthy individuals [16Polo C, Pérez JL, Mielnichuck A, Fedele CG, Niubò J, Tenorio A. Prevalence and patterns of polyomavirus urinary excretion in immunocompetent adults and children Clin Microbiol Infect 2004; 10(7): 640-4.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00882.x] [PMID: 15214877] ]. Recently, it has been considered as one of the causative agents of nephropathy in renal transplant recipients. Thus, these two viruses are very important in the clinical setting.

In this study, we assessed the ability of the GP method to detect species of virus. Secondly, we compared the results of the GP method with the conventional identification method. Finally, in order to provide evidence that this method can be used in clinical cases, we conducted the GP method with urine samples from two individuals as a trial.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. DNA Samples

Whole genome plasmids of 13 JCPyV isolates [17Ikegaya H, Iwase H, Saukko PJ, Akutsu T, Sakurada K, Yoshino M. JC viral DNA chip allows geographical localization of unidentified cadavers for rapid identification Forensic Sci Int Genet 2008; 2(1): 54-60.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2007.08.009] [PMID: 19083790] ] (Table 1) and 3 BKPyV isolates [18Nukuzuma S, Takasaka T, Zheng HY, et al. Subtype I BK polyomavirus strains grow more efficiently in human renal epithelial cells than subtype IV strains J Gen Virol 2006; 87(Pt 7): 1893-901.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.81698-0] [PMID: 16760391] ] (Table 2), using pUC-19 as a vector, were used in this study (1.0 ng/µL). For the clinical case study, we collected urine samples from a JCPyV positive individual and from a negative individual whose urinary infection was confirmed in another previous study using PCR amplification of the virus genome, and DNA was extracted using QIAmp DNA mini kits (QIAGEN, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The final concentration of DNA was set as 1.0 ng/µL and used in the following experiments. This study was approved by the institutional review board (No. G-98-1).

2.2. GP Method

2.2.1. Random PCR

The reaction mixture (25 μL) contained 17.5 pmol SP-1 primer (pfm12) (5′-agaacgcgcctg-3′) [19Biyani M, Nishigaki K. Sequence-specific and nonspecific mobilities of single-stranded oligonucleotides observed by changing the borate buffer concentration Electrophoresis 2003; 24(4): 628-33.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/elps.200390073] [PMID: 12601730] , 20Nishigaki K, Saito A, Takashi H, Naimuddin M. Whole genome sequence-enabled prediction of sequences performed for random PCR products of Escherichia coli Nucleic Acids Res 2000; 28(9): 1879-84.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.9.1879] [PMID: 10756186] ], 0.16 mM each dNTP, 1× ExTaq Buffer, 0.5 U ExTaq polymerase (TaKaRa Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan), and 1.0 ng of crude DNA. We checked other primers for random PCR in the preliminary experiment; however, SP-1 was the most successful primer for the random PCR.

PCR was performed using a PC-320 Thermal Cycler (ASTEC, Fukuoka, Japan). After denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 26°C for 1 min, and 47°C for 1 min were performed, followed by extension at 47°C for 5 min.

2.2.2. Internal Standards [1Nishigaki K, Naimuddin M, Hamano K. Genome profiling: a realistic solution for genotype-based identification of species J Biochem 2000; 128(1): 107-12.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022719] [PMID: 10876164] ]

M13 phage and pBR322 were used as the internal reference samples according to the GP method. Reference 1 (Ref1; M13 phage DNA) was approximately 200 bp, and reference 2 (Ref2; pBR322 DNA) was approximately 900 bp. Ref1 was PCR amplified using the primers MA1 (5′-tgctacgtctcttc-cgatgctgtctttcgc-3′) and MA2 (5′-ccttgaattctatcggtt-tatca-3′). The total reaction volume of 50 μL contained 1.0 μg M13 phage DNA (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.), 0.75 U ExTaq DNA polymerase, 200 μM dNTPs, 0.6 μM primers, and a PCR buffer supplied by the manufacturer. PCR amplification was performed for 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 63°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s, followed by a final step of 72°C for 5 min. Ref2 was PCR amplified using the primers Ref6F (5′-gccggcatcaccggcgcca-caggtgcggttg-3′) and Ref6R (5′-tagcgaggtgccgccggc-ttccattcaggtc-3′). The total reaction volume of 50 μL contained 0.25 μg pBR322 DNA (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.), 1.25 U ExTaq DNA polymerase, 200 μM dNTPs, 0.7 μM primers, and a PCR buffer supplied by the manufacturer. PCR amplification was performed for 25 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final step of 72°C for 30 s.

2.2.3. Temperature Gradient Gel Electrophoresis

The 0.3μL of two reference DNAs as internal reference standards described above and 1μL of 6X loading buffer were added to the 4.4μL amplified DNA samples. Then, the total 6μL of DNA sample was electrophoresed at a temperature gradient on a 6% polyacrylamide gel for 10 min at a constant voltage of 100 V [21Nishigaki K, Tsubota M, Miura T, Chonan Y, Husimi Y. Structural analysis of nucleic acids by precise denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis: I. Methodology J Biochem 1992; 111(2): 144-50.

[PMID: 1569038] , 22Biyani M, Nishigaki K. Sequence-specific and nonspecific mobilities of single-stranded oligonucleotides observed by changing the borate buffer concentration Electrophoresis 2003; 24(4): 628-33.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/elps.200390073] [PMID: 12601730] ] using µTG (TAITEC, Saitama, Japan). The temperature gradient was 15–65°C. Then, the electrophoresed gel was stained in a 0.1 M NaCl solution containing 0.03% GelRed (Biotium, Inc., CA, USA) for 10 min and a photograph of the gel was taken under UV light using a LAS 4000 Mini (FUJIFILM, Tokyo, Japan). The sensitivity of the GP method was checked by visible amplified fragments using diluted plasmid DNA samples (X1, X10, X100, X1000, X10000, and X10000).

2.4. Cluster Analysis

From the photograph of the electrophoresed gel, spiddos, which indicate melting points of ds DNA, were selected manually. The spiddos were adjusted using the spiddos of the reference internal standards, and Pattern Similarity Scores (PaSSs) were calculated using micro-temperature gradient gel electrophoresis analyzer software [23Nishigaki K, Husimi Y, Masuda M, Kaneko K, Tanaka T. Strand dissociation and cooperative melting of double-stranded DNAs detected by denaturant gradient gel electrophoresis J Biochem 1984; 95(3): 627-35.

[PMID: 6202679] -28Kouduka M, Sato D, Komori M, et al. A solution for universal classification of species based on genomic DNA Int J Plant Genomics 2007; 2007: 27894.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2007/27894] [PMID: 18253463] ]. Below is the equation for PaSS calculation.

Difference of the coordinates of spiddos (=(θ,μ)) reflects the difference of the DNA sequence. The PaSS value represents the degree of similarity between genomes. The PaSS value ranges from 0 to 1.0; if the genomes match perfectly, then the PaSS value is 1.0. From the calculated PaSS values, all samples were cluster analyzed using the Ward method [29Ward JH Jr. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function J Am Stat Assoc 1963; 58(301): 236-44.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1963.10500845] ].

3. SEQUENCING AND PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS

3.1. Sequencing

A BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA) was used in this study. All procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 5 μL of reaction mixture contained 0.5 µL of sequencing primers P-1 (5′-cacaagcttttttgggacactaacaggagg-3′; nt 2107–2127) and P-2 (5′-gattctgcagcagaagactctggacatg-3′; nt 2762–2742 in the JCPyV [MadI] genome [GenBank accession no. J02226]) for JCPyV, or 327-1PST (5′-gcctgcagcaagtgc-caaaactactaat-3′; nt 1630–1649 in the BKPyV [Dunlop] genome [GenBank accession no. V01108; NCBI no. NC_001538Kamgang B, Brengues C, Fontenille D, Njiokou F, Simard F, Paupy C. Genetic structure of the tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, in Cameroon (Central Africa) PLoS One 2011; 6(5): e20257.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020257] [PMID: 21629655] ]) and 327-2HIN (5′-gcaagcttgcatgaagg-ttaagcatgc-3′; nt 1956–1937) for BKPyV [30Ikegaya H, Motani H, Saukko P, Sato K, Akutsu T, Sakurada K. BK virus genotype distribution offers information of tracing the geographical origins of unidentified cadaver Forensic Sci Int 2007; 173(1): 41-6.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.01.022] [PMID: 17324543] ], and 3 µL plasmid DNA. The cycle sequencing conditions were an initial step of 1 min at 96°C and 25 cycles of 10 s at 96°C, 5 s at 50°C, and 4 min at 60°C using a PC-320 Thermal Cycler. A 310 Genetic Analyzer (Life Tech-nologies, city, CA) was used to determine the 610 bp IG region of JCPyV or 287 bp typing region of BKPyV. By sequencing these typing regions of both viruses, we confirmed the virus isolates. After confirmation, we downloaded the whole genome data of all isolates from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

Using the downloaded whole genome sequences of all isolates, phylogenetic analysis was performed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method with maximum substitution. Molecular Evolution Genetic Analysis ver.4 [31Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0 Mol Biol Evol 2007; 24(8): 1596-9.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm092] [PMID: 17488738] ] was used for the analysis.

4. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t test, with the significance set at the 1% level

5. RESULTS

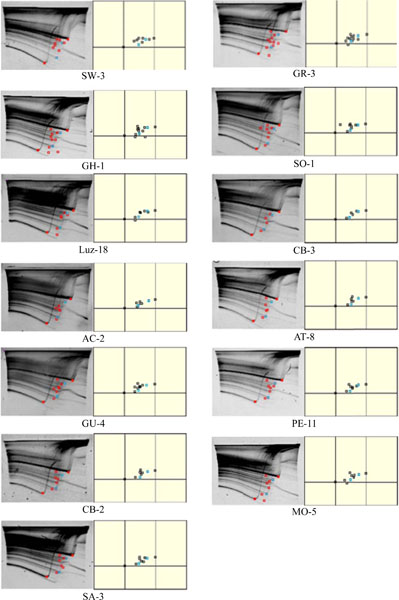

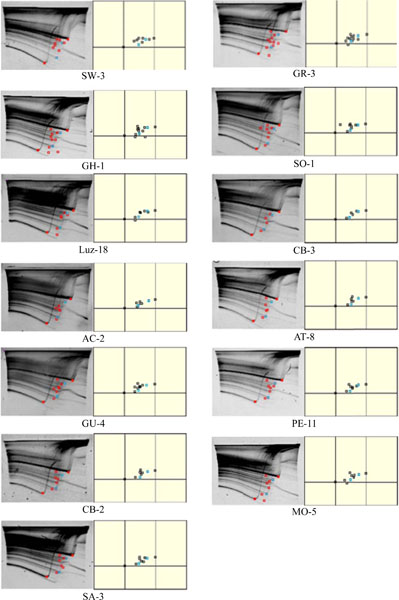

For the GP method, the average number of spiddos obtained was 8.23 for JCPyV and 5.0 for BKPyV (Table 3). The amplified DNA fragments were observed in the samples diluted up to X10000. The number of common spiddos in the same virus species was 2 for JCPyV (Fig. 2 ) and 3

) and 3 for BKPyV (Fig. 3

for BKPyV (Fig. 3 ). The PaSSs were 0.9757–0.9895 among JCPyV isolates (mean ± standard deviation [SD]: 0.9836 ± 0.0026) and 0.9792–0.9853 among BKPyV isolates (mean ± SD: 0.9828 ± 0.0032) (Table 4). Comparing the BKPyV isolates to the JCPyV isolates, the PaSS value among BKPYV isolates was 0.9632-0.9802 (0.9710 ± 0.0039) (Table 4). There was a statistically significant difference between the PaSS values among these two virus species (P<0.01). When the GP method was replicated, the PaSS values in the same virus strain were 0.9768–0.9893 (mean ± SD: 0.9841 ± 0.0036).

). The PaSSs were 0.9757–0.9895 among JCPyV isolates (mean ± standard deviation [SD]: 0.9836 ± 0.0026) and 0.9792–0.9853 among BKPyV isolates (mean ± SD: 0.9828 ± 0.0032) (Table 4). Comparing the BKPyV isolates to the JCPyV isolates, the PaSS value among BKPYV isolates was 0.9632-0.9802 (0.9710 ± 0.0039) (Table 4). There was a statistically significant difference between the PaSS values among these two virus species (P<0.01). When the GP method was replicated, the PaSS values in the same virus strain were 0.9768–0.9893 (mean ± SD: 0.9841 ± 0.0036).

The results of cluster analysis after the GP method are shown in Fig. (4 ). The JCPyV and BKPyV clusters were apparently independent. The JCPyV strains formed two major clusters. One of the clusters contained the SW-3, GR-3, GH-1, and CB-2 strains, while the other cluster contained the remaining strains.

). The JCPyV and BKPyV clusters were apparently independent. The JCPyV strains formed two major clusters. One of the clusters contained the SW-3, GR-3, GH-1, and CB-2 strains, while the other cluster contained the remaining strains.

The results of NJ phylogenetic analysis using whole genome sequences are shown in Fig. (5 ). The SW-3, GR-3, and GH-1 strains formed one cluster. As all JCPyV strains classified by the conventional method were not the same as that classified by the GP method, we were unable to distinguish the JCPyV and BKPyV genotypes perfectly using the latter method. However we were able at least to distinguish between the two virus species.

). The SW-3, GR-3, and GH-1 strains formed one cluster. As all JCPyV strains classified by the conventional method were not the same as that classified by the GP method, we were unable to distinguish the JCPyV and BKPyV genotypes perfectly using the latter method. However we were able at least to distinguish between the two virus species.

Finally, we analyzed clinical samples. Fig. (6a) shows the results of the GP method using the JCPyV positive urine sample. JCPyV specific spiddos were obtained in this sample. There were also numerous spiddos obtained from this sample. Those obtained spiddos were different from those of the plasmid DNA samples. Sequencing analysis was also performed on this sample, and this JCPyV genotype was CY. Fig. (6b)

shows the results of the GP method using the JCPyV positive urine sample. JCPyV specific spiddos were obtained in this sample. There were also numerous spiddos obtained from this sample. Those obtained spiddos were different from those of the plasmid DNA samples. Sequencing analysis was also performed on this sample, and this JCPyV genotype was CY. Fig. (6b) shows the results from the GP method using the JCPyV negative urine sample. There were no JCPyV specific spiddos obtained in this sample.

shows the results from the GP method using the JCPyV negative urine sample. There were no JCPyV specific spiddos obtained in this sample.

6. DISCUSSION

Though the homology between JCPyV and BKPyV is about 70%, the number of the spiddos were much higher in the JCPyV. This is because the random primer attaches to and amplifies different DNA sequences. The homology between JCPyV strains is about 99%; however, several different spiddos are obtained. It also is considered that amplified DNA fragments might include vector DNA as well as virus DNA. However, the virus specific spiddos show that among those amplified fragments, virus DNA were surely amplified, and the number of the common spiddos is 2 or 3. Though these numbers are relatively small, if we consider the small size of virus genome, it is reasonable. Small differences, such as between the isolates in the same virus species, are calculated by the PaSS score. So the number of the spiddos is not used for the determination of virus species. The number of the spiddos is important for the calculation of PaSS. If the number of the spiddos is rich, we can get more reliable PaSS results. Because of the random PCR system, we cannot avoid the amplification of other contaminated DNA. Therefore specific spiddos are the most important for the diagnosis of those viruses.

The results of cluster analysis obtained using the GP method did not agree completely with those obtained using phylogenetic analysis. Although we could discriminate between virus species, we could not discriminate virus genotype with the GP method. We consider one of the main reasons for this to be that cluster analysis does not include molecular evolution aspects; it only classifies a similar spiddo pattern that represents a genome sequence. In addition, as around 70% of the genome sequence of BKPyV is the same as that of JCPyV, they can be distinguished using the GP method. However, because around only 1% of the genome sequence is different among the JCPyV or BKPyV isolates, it might be difficult to distinguish such small differences using the GP method. These small differences are very important for us to analyze population history not only in the studies using JCPyV and BKPyV [17Ikegaya H, Iwase H, Saukko PJ, Akutsu T, Sakurada K, Yoshino M. JC viral DNA chip allows geographical localization of unidentified cadavers for rapid identification Forensic Sci Int Genet 2008; 2(1): 54-60.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2007.08.009] [PMID: 19083790] , 32Sugimoto C, Hasegawa M, Kato A, et al. Evolution of human Polyomavirus JC: implications for the population history of humans J Mol Evol 2002; 54(3): 285-97.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00239-001-0009-x] [PMID: 11847555] -37Nishimoto Y, Takasaka T, Hasegawa M, et al. Evolution of BK virus based on complete genome data J Mol Evol 2006; 63(3): 341-52.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00239-005-0092-5] [PMID: 16897259] ] but also in other studies [38Kamgang B, Brengues C, Fontenille D, Njiokou F, Simard F, Paupy C. Genetic structure of the tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, in Cameroon (Central Africa) PLoS One 2011; 6(5): e20257.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020257] [PMID: 21629655] , 39Underhill PA, Kivisild T. Use of y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA population structure in tracing human migrations Annu Rev Genet 2007; 41: 539-64.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130407] [PMID: 18076332] ]. In the current GP method, because the spiddos are selected manually, the researcher’s technique may affect the reproducibility of the results. In our previous study, when one highly skilled researcher performed the GP method 5 times using the same sample, the PaSS value was 0.9905 ± 0.0024. If the GP method had complete reproducibility, the PaSS value should have been 1.0. As a result, the difference of the PaSS value in the GP procedure was around 1% [2Suwa N, Ikegaya H, Takasaka T, Nishigaki K, Sakurada K. Human blood identification using the genome profiling method Leg Med (Tokyo) 2012; 14(3): 121-5.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2012.01.001] [PMID: 22285643] ]. Differences of electrophoresis are standardized with the use of internal standards, and these differences do not affect the PaSS value. In this study, we performed the GP method twice using the same samples, and the difference in the PaSS value was 0.9941 ± 0.0036. It is considered that this difference was also the result of the manual procedure. To improve reproducibility, it may be necessary not only to increase the number of trials and improve researchers’ technical skills, but also to perform automated selection of spiddos using special software. If the spiddos are selected automatically, we will always be able to obtain the same spiddos; the PaSS values will be 1.0. Finally, the spiddos used in the calculation of PaSS might include the amplified fragment of the vector DNA. That dilute the difference among the each viral strains. Because of the small genome size of those viruses, the number of the specific spiddos is low. Therefore, we consider it might much more reliable to use all obtained spiddos for the calculation.

In this study, the whole procedure required around 6 hours using the GP method and around 36 hours for the conventional method. Especially, checking the obtained sequence in the electropherograms generated by the sequencer requires a considerable amount of time. The GP method does not require such time-consuming procedures or expensive reagents and machines.

The sensitivity of the GP method was also very high. However, the detection from plasmid DNA samples may different from the detection from clinical urine samples. We will try to examine the sensitivity using the clinical materials.

Some of the spiddos were present only in JCPyV or BKPyV. These virus-specific spiddos represent virus-specific sequences. Therefore, if many kinds of virus genome are analyzed in advance with the GP method, it may be possible to identify virus species by detecting virus-specific spiddos.

In our trials using clinical samples, we could detect many spiddos (Fig. 6 ). In the JCPyV positive urine sample (Fig. 6a

). In the JCPyV positive urine sample (Fig. 6a ), there were also numerous spiddos obtained from this sample. These spiddos might have resulted from the amplification of human DNA contained in the urine. The number of human cells in the urine varies with the individual, and obtained spiddos were different from those of plasmid DNA samples. That might be due to the fact that most of the materials for amplification were used to amplify the human DNA. However, we could obtain the virus specific spiddos. In the JCPyV negative urine sample (Fig. 6b

), there were also numerous spiddos obtained from this sample. These spiddos might have resulted from the amplification of human DNA contained in the urine. The number of human cells in the urine varies with the individual, and obtained spiddos were different from those of plasmid DNA samples. That might be due to the fact that most of the materials for amplification were used to amplify the human DNA. However, we could obtain the virus specific spiddos. In the JCPyV negative urine sample (Fig. 6b ), there were no JCPyV specific spiddos obtained. Neither could we obtain many spiddos in this sample, indicating that the urine contain little DNA of human or of microorganisms. The amount of human DNA in the urine may be also affected by the urinary virus infection. With this result, we consider that we may be able to utilize the GP method to detect polyomavirus in urine samples. Of course, for this purpose it is necessary to validate this method with a large number of cases.

), there were no JCPyV specific spiddos obtained. Neither could we obtain many spiddos in this sample, indicating that the urine contain little DNA of human or of microorganisms. The amount of human DNA in the urine may be also affected by the urinary virus infection. With this result, we consider that we may be able to utilize the GP method to detect polyomavirus in urine samples. Of course, for this purpose it is necessary to validate this method with a large number of cases.

CONCLUSION

In this study we showed that the GP method can be used to discriminate among different human polyoma-virus species. In addition, it may be used for other virus species. The GP method is a very simple and inexpensive tool to analyze virus genomes. It does not require virus-specific primers, so although it cannot distinguish virus genotypes, it may be used for virus screening. We demonstrated the possibility to utilize this method to detect urinary viruses using test clinical test cases. We plan to analyze various viruses in clinical samples in the near future.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article contents have no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Nukuzuma for providing plasmid samples, and Prof. Nishigaki and Mr. Takasaka for helpful discussions.

This study was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for scientific research (C) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

| [1] | Nishigaki K, Naimuddin M, Hamano K. Genome profiling: a realistic solution for genotype-based identification of species J Biochem 2000; 128(1): 107-12. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022719] [PMID: 10876164] |

| [2] | Suwa N, Ikegaya H, Takasaka T, Nishigaki K, Sakurada K. Human blood identification using the genome profiling method Leg Med (Tokyo) 2012; 14(3): 121-5. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2012.01.001] [PMID: 22285643] |

| [3] | Hirata R, Takasaka T, Miyamori D, et al. Use of the profiling method for the identification of saliva and sweat samples Jap J Forensic Sci Tech 2013; 18(1): 79-83. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3408/jafst.18.79] |

| [4] | Takasaka T, Sakurada K, Akutsu T, Nishigaki K, Ikegaya H. Trials of the detection of semen and vaginal fluid RNA using the genome profiling method Leg Med (Tokyo) 2011; 13(5): 265-7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2011.05.001] [PMID: 21684187] |

| [5] | Raj GV, Khalili K. Transcriptional regulation: lessons from the human neurotropic polyomavirus, JCV Virology 1995; 213(2): 283-91. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/viro.1995.0001] [PMID: 7491753] |

| [6] | Seif I, Khoury G, Dhar R. The genome of human papovavirus BKV Cell 1979; 18(4): 963-77. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(79)90209-5] [PMID: 229976] |

| [7] | Padgett BL, Walker DL. New human papovaviruses Prog Med Virol 1976; 22: 1-35. [PMID: 62371] |

| [8] | Khalili K, Gordon J, White MK. The polyomavirus, JCV and its involvement in human disease Adv Exp Med Biol 2006; 577: 274-87. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/0-387-32957-9_20] [PMID: 16626043] |

| [9] | Taguchi F, Kajioka J, Miyamura T. Prevalence rate and age of acquisition of antibodies against JC virus and BK virus in human sera Microbiol Immunol 1982; 26(11): 1057-64. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1348-0421.1982.tb00254.x] [PMID: 6300615] |

| [10] | Kitamura T, Aso Y, Kuniyoshi N, Hara K, Yogo Y. High incidence of urinary JC virus excretion in nonimmunosuppressed older patients J Infect Dis 1990; 161(6): 1128-33. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/infdis/161.6.1128] [PMID: 2161040] |

| [11] | Kunitake T, Kitamura T, Guo J, Taguchi F, Kawabe K, Yogo Y. Parent-to-child transmission is relatively common in the spread of the human polyomavirus JC virus J Clin Microbiol 1995; 33(6): 1448-51. [PMID: 7650165] |

| [12] | Kato A, Kitamura T, Sugimoto C, et al. Lack of evidence for the transmission of JC polyomavirus between human populations Arch Virol 1997; 142(5): 875-82. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s007050050125] [PMID: 9191854] |

| [13] | Suzuki M, Zheng HY, Takasaka T, et al. Asian genotypes of JC virus in Japanese-Americans suggest familial transmission J Virol 2002; 76(19): 10074-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.76.19.10074-10078.2002] [PMID: 12208989] |

| [14] | Gardner SD, Field AM, Coleman DV, Hulme B. New human papovavirus (B.K.) isolated from urine after renal transplantation Lancet 1971; 1(7712): 1253-7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(71)91776-4] [PMID: 4104714] |

| [15] | Giraud G, Bogdanovic G, Priftakis P, et al. The incidence of hemorrhagic cystitis and BK-viruria in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell recipients according to intensity of the conditioning regimen Haematologica 2006; 91(3): 401-4. [PMID: 16531266] |

| [16] | Polo C, Pérez JL, Mielnichuck A, Fedele CG, Niubò J, Tenorio A. Prevalence and patterns of polyomavirus urinary excretion in immunocompetent adults and children Clin Microbiol Infect 2004; 10(7): 640-4. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00882.x] [PMID: 15214877] |

| [17] | Ikegaya H, Iwase H, Saukko PJ, Akutsu T, Sakurada K, Yoshino M. JC viral DNA chip allows geographical localization of unidentified cadavers for rapid identification Forensic Sci Int Genet 2008; 2(1): 54-60. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2007.08.009] [PMID: 19083790] |

| [18] | Nukuzuma S, Takasaka T, Zheng HY, et al. Subtype I BK polyomavirus strains grow more efficiently in human renal epithelial cells than subtype IV strains J Gen Virol 2006; 87(Pt 7): 1893-901. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.81698-0] [PMID: 16760391] |

| [19] | Biyani M, Nishigaki K. Sequence-specific and nonspecific mobilities of single-stranded oligonucleotides observed by changing the borate buffer concentration Electrophoresis 2003; 24(4): 628-33. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/elps.200390073] [PMID: 12601730] |

| [20] | Nishigaki K, Saito A, Takashi H, Naimuddin M. Whole genome sequence-enabled prediction of sequences performed for random PCR products of Escherichia coli Nucleic Acids Res 2000; 28(9): 1879-84. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.9.1879] [PMID: 10756186] |

| [21] | Nishigaki K, Tsubota M, Miura T, Chonan Y, Husimi Y. Structural analysis of nucleic acids by precise denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis: I. Methodology J Biochem 1992; 111(2): 144-50. [PMID: 1569038] |

| [22] | Biyani M, Nishigaki K. Sequence-specific and nonspecific mobilities of single-stranded oligonucleotides observed by changing the borate buffer concentration Electrophoresis 2003; 24(4): 628-33. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/elps.200390073] [PMID: 12601730] |

| [23] | Nishigaki K, Husimi Y, Masuda M, Kaneko K, Tanaka T. Strand dissociation and cooperative melting of double-stranded DNAs detected by denaturant gradient gel electrophoresis J Biochem 1984; 95(3): 627-35. [PMID: 6202679] |

| [24] | Naimuddin M, Kurazono T, Nishigaki K. Commonly conserved genetic fragments revealed by genome profiling can serve as tracers of evolution Nucleic Acids Res 2002; 30(10): e42. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/30.10.e42] [PMID: 12000847] |

| [25] | Biyani M, Nishigaki K. Structural characterization of ultra-stable higher-ordered aggregates generated by novel guanine-rich DNA sequences Gene 2005; 364: 130-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2005.05.041] [PMID: 16146675] |

| [26] | Naimuddin M, Kurazono T, Zhang Y, Watanabe T, Yamaguchi M, Nishigaki K. Species-identification dots: a potent tool for developing genome microbiology Gene 2000; 261(2): 243-50. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00502-3] [PMID: 11167011] |

| [27] | Kouduka M, Matuoka A, Nishigaki K. Acquisition of genome information from single-celled unculturable organisms (radiolaria) by exploiting genome profiling (GP) BMC Genomics 2006; 7: 135. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-7-135] [PMID: 16740170] |

| [28] | Kouduka M, Sato D, Komori M, et al. A solution for universal classification of species based on genomic DNA Int J Plant Genomics 2007; 2007: 27894. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2007/27894] [PMID: 18253463] |

| [29] | Ward JH Jr. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function J Am Stat Assoc 1963; 58(301): 236-44. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1963.10500845] |

| [30] | Ikegaya H, Motani H, Saukko P, Sato K, Akutsu T, Sakurada K. BK virus genotype distribution offers information of tracing the geographical origins of unidentified cadaver Forensic Sci Int 2007; 173(1): 41-6. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.01.022] [PMID: 17324543] |

| [31] | Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0 Mol Biol Evol 2007; 24(8): 1596-9. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm092] [PMID: 17488738] |

| [32] | Sugimoto C, Hasegawa M, Kato A, et al. Evolution of human Polyomavirus JC: implications for the population history of humans J Mol Evol 2002; 54(3): 285-97. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00239-001-0009-x] [PMID: 11847555] |

| [33] | Kato A, Sugimoto C, Zheng HY, Kitamura T, Yogo Y. Lack of disease-specific amino acid changes in the viral proteins of JC virus isolates from the brain with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy Arch Virol 2000; 145(10): 2173-82. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s007050070047] [PMID: 11087099] |

| [34] | Takasaka T, Sugimoto C, Zheng H, Kitamura T, Yogo Y. African origin of a genotype (Af2) of JC virus spread in not only Africa but also western and southern Asia Am J Phys Anthropol 2006; 129(3): 465-72. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20208] [PMID: 16331656] |

| [35] | Takasaka T, Miranda JJ, Sugimoto C, et al. Genotypes of JC virus in Southeast Asia and the western Pacific: implications for human migrations from Asia to the Pacific Anthropol Sci 2006; 112: 53-9. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1537/ase.00086] |

| [36] | Zheng HY, Sugimoto C, Hasegawa M, et al. Phylogenetic relationships among JC virus strains in Japanese/Koreans and Native Americans speaking Amerind or Na-Dene J Mol Evol 2003; 56(1): 18-27. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00239-002-2376-3] [PMID: 12569419] |

| [37] | Nishimoto Y, Takasaka T, Hasegawa M, et al. Evolution of BK virus based on complete genome data J Mol Evol 2006; 63(3): 341-52. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00239-005-0092-5] [PMID: 16897259] |

| [38] | Kamgang B, Brengues C, Fontenille D, Njiokou F, Simard F, Paupy C. Genetic structure of the tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, in Cameroon (Central Africa) PLoS One 2011; 6(5): e20257. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020257] [PMID: 21629655] |

| [39] | Underhill PA, Kivisild T. Use of y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA population structure in tracing human migrations Annu Rev Genet 2007; 41: 539-64. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130407] [PMID: 18076332] |

| [40] | Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap Evolution 1985; 39: 783-91. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2408678] |