- Home

- About Journals

-

Information for Authors/ReviewersEditorial Policies

Publication Fee

Publication Cycle - Process Flowchart

Online Manuscript Submission and Tracking System

Publishing Ethics and Rectitude

Authorship

Author Benefits

Reviewer Guidelines

Guest Editor Guidelines

Peer Review Workflow

Quick Track Option

Copyediting Services

Bentham Open Membership

Bentham Open Advisory Board

Archiving Policies

Fabricating and Stating False Information

Post Publication Discussions and Corrections

Editorial Management

Advertise With Us

Funding Agencies

Rate List

Kudos

General FAQs

Special Fee Waivers and Discounts

- Contact

- Help

- About Us

- Search

Open Chemistry Journal

(Discontinued)

ISSN: 1874-8422 ― Volume 8, 2021

Isolation of Phthalates and Terephthalates from Plant Material – Natural Products or Contaminants?

Thies Thiemann1, *

Abstract

Dialkyl phthalates have been used as plasticizers in polymers for decades. As mobile, small weight molecules, phthalates have entered the environment, where they have become ubiquitous. On the other hand, phthalates continue to be isolated from natural sources, plants, bacteria and fungi as bona fide natural products. Here, doubt remains as to whether the phthalates represent actual natural products or whether they should all be seen as contaminants of anthropogenic origin. The following article will review the material as presented in the literature.

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2021Volume: 8

First Page: 1

Last Page: 36

Publisher Id: CHEM-8-1

DOI: 10.2174/1874842202108010001

Article History:

Received Date: 28/07/2020Revision Received Date: 13/10/2020

Acceptance Date: 03/11/2020

Electronic publication date: 02/03/2021

Collection year: 2021

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

* Address correspondence to this author at Department of Chemistry, College of Science, United Arab Emirates University, PO Box 15551, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates; E-mails: thies@uaeu.ac.ae; thiesthiemann@yahoo.de

| Open Peer Review Details | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Manuscript submitted on 28-07-2020 |

Original Manuscript | Isolation of Phthalates and Terephthalates from Plant Material – Natural Products or Contaminants? | |

1. INTRODUCTION

Phthalates are ubiquitous compounds that have been used as plasticizers in polymers for many decades, starting in the late 1920s – early 1930s, where a number of patents showed the rising interest in these products at the time [1Denune, Y.H. (Schaack Bros. Chem. Works), Esters of hexanol. US Pat. 1702188A, 1928., 2De Witt, G.G.; Eastby, L.W. (EI Du Pont de Nemours Co.), Esters and process for producing them. US Pat. 1993736A, 1931.] and where phthalates started to replace camphor-based plasticizers. Phthalates have been especially associated with the emergence of plastics such as polyvinyl chloride [3Lorz, P.M.; Towae, F.K.; Enke, W.; Jäckh, R.; Bhargava, N.; Hillesheim, W. Phthalic Acid and Derivatives, 2007,

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14356007.a20_181.pub2] ]. At the same time, phthalates, many of which are environmentally quite mobile, have become pervasive pollutants of our biosphere, entering both water and soil. Although especially the low-MW phthalates can be readily degraded hydrolytically [4Huang, J.; Nkrumah, P.N.; Li, Y.; Appiah-Sefah, G. Chemical behavior of phthalates under abiotic conditions in landfills. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol., 2013, 224, 39-52.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5882-1_2] [PMID: 23232918] ], photochemically [5Gmurek, M.; Olak-Kucharczyk, M.; Ledakowicz, S. Photochemical decomposition of endocrine disrupting compounds - A review. Chem. Eng. J., 2017, 310, 437-456.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2016.05.014] ] and microbially [6Boll, M.; Geiger, R.; Junghare, M.; Schink, B. Microbial degradation of phthalates: biochemistry and environmental implications. Environ. Microbiol. Rep., 2020, 12(1), 3-15.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.12787] [PMID: 31364812] ], detectable amounts of phthalates can be found almost everywhere, including in our diet [7Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Kannan, K. A review of biomonitoring of phthalate exposures. Toxics, 2019, 7(2), 21.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/toxics7020021] [PMID: 30959800] ]. Low-MW phthalates are dermally absorbed relatively easily. This leads to the identification of phthalates and phthalate derivatives in humans, easily detectable in urine [8Philips, E.M.; Santos, S.; Steegers, E.A.P.; Asimakopoulos, A.G.; Kannan, K.; Trasande, L.; Jaddoe, V.W. V. Maternal bisphenol and phthalate urine concentrations and weight gain during pregnancy Environ. Intern., 2020, 105342..], breast milk [9Fan, J.C.; Ren, R.; Jin, Q.; He, H.L.; Wang, S.T. Detection of 20 phthalate esters in breast milk by GC-MS/MS using QuEChERS extraction method. Food Addit. Contam., A, 2019, 36, 1551-1558.], and blood [10Albro, P.W.; Corbett, J.T. Distribution of di- and mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in human plasma. Transfusion, 1978, 18(6), 750-755.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1537-2995.1978.18679077962.x] [PMID: 83042] ]. It has been found that the concentrations of phthalates in the air are often higher in urban than in rural areas [11Rudel, R.A.; Dodson, R.E.; Perovich, L.J.; Morello-Frosch, R.; Camann, D.E.; Zuniga, M.M.; Yau, A.Y.; Just, A.C.; Brody, J.G. Semivolatile endocrine-disrupting compounds in paired indoor and outdoor air in two northern California communities. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2010, 44(17), 6583-6590.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/es100159c] [PMID: 20681565] , 12He, M.J.; Lu, J.F.; Ma, J.Y.; Wang, H.; Du, X.F. Organophosphate esters and phthalate esters in human hair from rural and urban areas, Chongqing, China: Concentrations, composition profiles and sources in comparison to street dust. Environ. Pollut., 2018, 237, 143-153.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.02.040] [PMID: 29482020] ]. Nevertheless, phthalates have been identified in soil, for instance, as leachates from plastic mulching/plastic film greenhouses [13Shi, M.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, G.; Quan, H.; He, H. Plastic film mulching increased the accumulation and human health risks of phthalate esters in wheat grains. Environ. Pollut., 2019, 250, 1-7.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.064] [PMID: 30981178] , 14Wang, J.; Chen, G.; Christie, P.; Zhang, M.; Luo, Y.; Teng, Y. Occurrence and risk assessment of phthalate esters (PAEs) in vegetables and soils of suburban plastic film greenhouses. Sci. Total Environ., 2015, 523, 129-137.

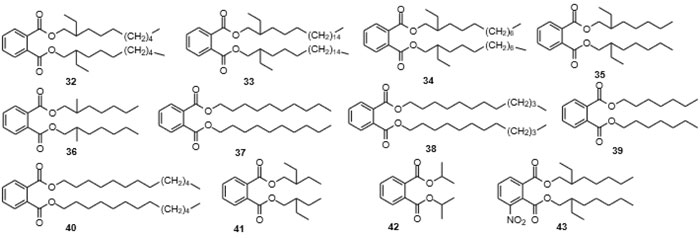

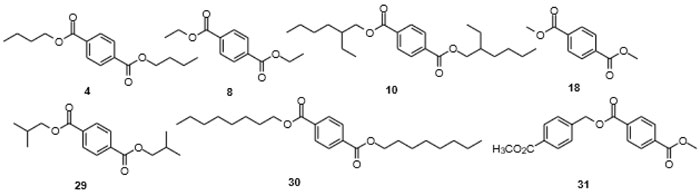

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.02.101] [PMID: 25863503] ], and also because they are used as agricultural adjuvants in pesticides [15Iida, T.; Yanagisawa, K. (Sumitomo Chem. Co., Ltd., Japan) Agrochemical solid formulation, method for preparation and use in pest control, FR 3047639, 2017.] (Fig. 1 ).

).

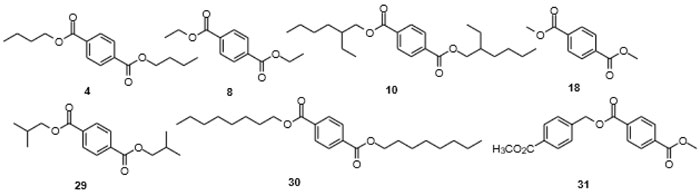

Phthalates have been isolated from many plants, from algae, bacteria and fungi. In the natural product isolations, oftentimes, the phthalates were looked upon as plant secondary metabolites. As often is the case, after isolation of the products from the plant, the bioactivity of the compounds was studied. In regard to the phthalates, multiple researchers have remarked on various biological activities of the molecules. Intriguing is the comparison of these studies and the investigations of different governmental organizations on the health effects of phthalates as components of consumer products. Sometimes, there can be a disconnect when scientists in closely related but highly specialized, clearly demarcated research areas do not cross-disseminate their fields with information flow. In the case of the study of phthalates, academically, there seem to be rather different areas of research and development that little overlap and often show little data transfer: the development of new product formulations with phthalates, the analytical detection and quantification of phthalates in our daily products and in our environment, often coupled with the assessment of health implications, the study of the degradation of phthalates by bacteria and other microorganisms and lastly the isolation of phthalates as possible natural products from plants and other organisms. In view of the ubiquity of phthalates in our environment, few research papers on the isolation of phthalates from plants have asked whether these products might not be of anthropogenic origin. Nevertheless, two prior review articles have looked at the possibility that at least some of the isolated phthalates could indeed be natural products [16Zhang, H.; Hua, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Bai, X.; Wang, H. Organism-derived phthalate derivatives as bioactive natural products J. Environ. Sci., C, 2018, 36125, 17Ortiz, A.; Sansinenea, E. Di-2-ethylhexylphthalate may be a natural product, rather than a pollutant. J. Chem. (Hindawi), 2018.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2018/6040814] ], with a further essay asking the question of whether medicinal plants are polluted with phthalates [18Saeidnia, S.; Abdollahi, M. Are medicinal plants polluted with phthalates? Daru, 2013, 21(1), 43-45.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2008-2231-21-43] [PMID: 23718122] ]. In the current contribution, the author reassesses with the aid of published research articles how far phthalates isolated from organisms are indeed natural products or whether they can be seen mostly as contaminants. (Fig. 2 )

)

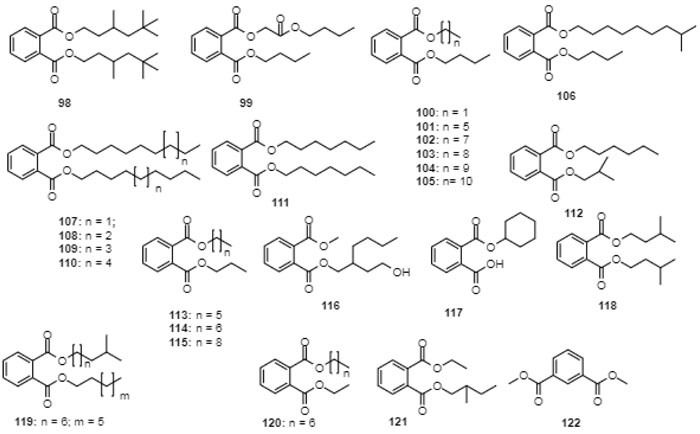

1.1. Phthalates – Trends in Production and Usage; Health Concerns

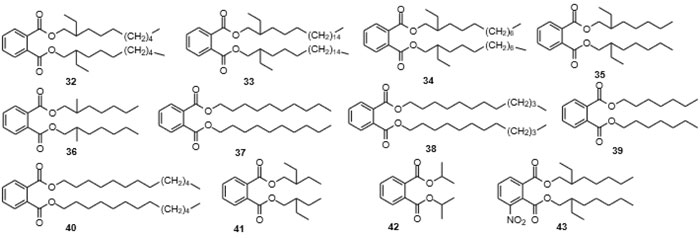

Of the roughly 60 different commercially produced phthalates, there are 26 phthalates that are relatively commonly used. The usage of the most common phthalates is shown in Table 1. In 2001, the breakdown of use of different types of phthalates in Europe was reported as follows: di(ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP, 9), 51%; diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP), 21%; diisononyl phthalate (DINP, 15), 11%; dibutyl phthalate (5), 2% and others, 17% [19Murphy, J. Additives for plastics – Handbook., (2nd ed. ), 2001,

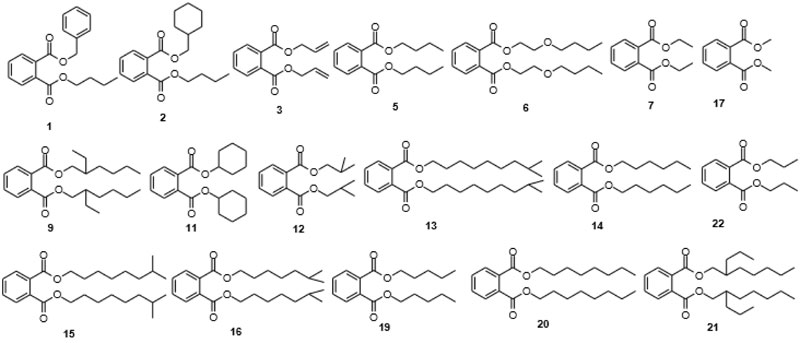

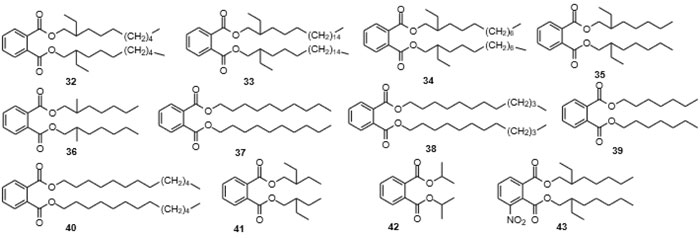

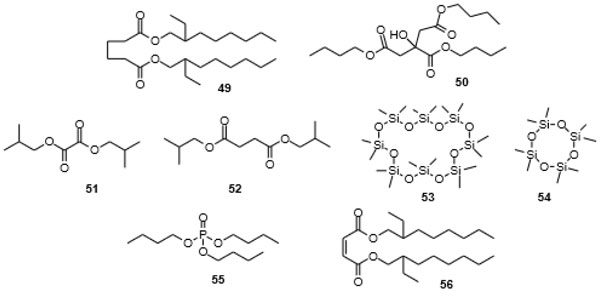

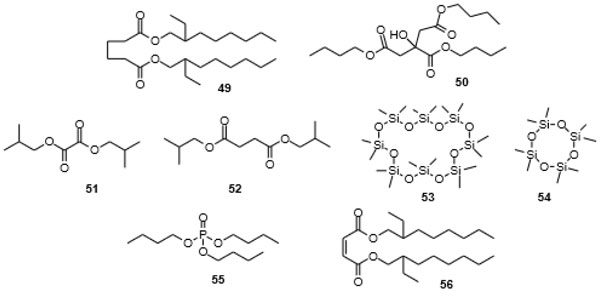

]. At that time, about 8.4 million tons of plasticizer were produced every year. Of DEHP (9), 3.0 million tons were produced in 2006 alone. In the late 2010s, many of the C3-C6 phthalates were replaced with higher MW C9-C13 phthalates [20Phthalates | Assessing and Managing Chemicals Under TSCA. www.epa.gov2012. https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/phthalates Retrieved on July 1stsup>, 2020], with DEHP (9) still abundantly being produced, but in different parts of the world, more and more being replaced by DINP (15). DINP (15) as a “high” phthalate has a longer residency time in plastics, which gives the plastics better durability. It must be noted that while oftentimes the higher branched phthalates are produced as a mixture of isomers, only one isomer for each phthalate is shown in the drawings and tables in the article. Overall, from 2010 onwards, non-phthalate plasticizers are increasingly invading the market. These include terephthalates (Fig. 3 ), epoxy, trimellitates, and some aliphatics/cycloaliphatics (mainly hydrogenated phtha- lates such as diisononyl cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylate [DINCH] which is a mixture of isomers which includes 44), alkane α,ω-dicarboxylates such as di(2-ethylhexyl) adipate (DEHA, 49), and alkane tricarboxylates such as acetyl tri-n-butyl citrate (ATBC, 50) and biomass-derived triglycerides [21Jia, P.; Xia, H.; Tang, K.; Zhou, Y. Plasticizers derived from biomass resources: a short review. Polymers (Basel), 2018, 10(12), 1303-1330.

), epoxy, trimellitates, and some aliphatics/cycloaliphatics (mainly hydrogenated phtha- lates such as diisononyl cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylate [DINCH] which is a mixture of isomers which includes 44), alkane α,ω-dicarboxylates such as di(2-ethylhexyl) adipate (DEHA, 49), and alkane tricarboxylates such as acetyl tri-n-butyl citrate (ATBC, 50) and biomass-derived triglycerides [21Jia, P.; Xia, H.; Tang, K.; Zhou, Y. Plasticizers derived from biomass resources: a short review. Polymers (Basel), 2018, 10(12), 1303-1330.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/polym10121303] [PMID: 30961228] ]). The market shares of these are forecasted to grow strongly as they continue to replace phthalates [22Plasticizers - Chemical Economics Handbook (CEH). IHS Markit, 2018.]. It is estimated that in 2005, 88% of the plasticizers produced were phthalates. The share of admittedly, a growing market declined to 65% in 2017, and it is predicted to decline even further to about 60% in 2022 [22Plasticizers - Chemical Economics Handbook (CEH). IHS Markit, 2018.].

|

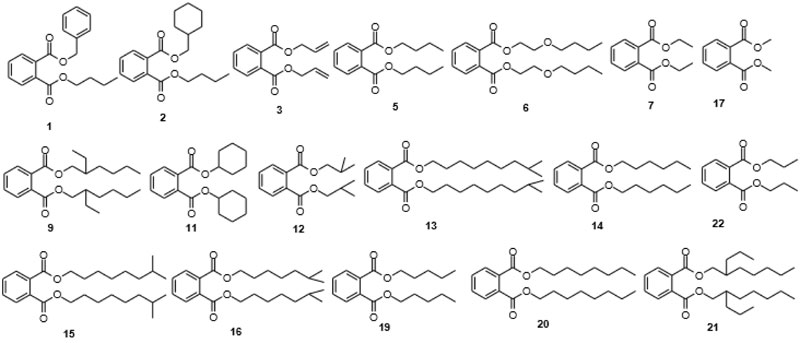

Fig. (1) Structures of some of the industrially most important phthalates. |

|

Fig. (2) Phthalates commonly isolated from natural sources. |

|

Fig. (3) Terephthalates isolated from natural sources. |

This is because of a growing disquiet that phthalates can have harmful effects. DEHP (9) has been found to be an endocrine disruptor [23Barakat, R.; Lin, P.C.; Park, C.J.; Zeineldin, M.; Zhou, S.; Rattan, S.; Brehm, E.; Flaws, J.A.; Ko, C.J. Germline-dependent transmission of male reproductive traits induced by an endocrine disruptor, di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate, in future generations. Sci. Rep., 2020, 10(1), 5705.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62584-w] [PMID: 32235866] ] and possible carcinogen [24Kim, J.H. Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate promotes lung cancer cell line A549 progression via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. J. Toxicol. Sci., 2019, 44(4), 237-244.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.2131/jts.44.237] [PMID: 30944277] ], and DINP (15) has also been put on the list of possible carcinogens [25Tas, I.; Zou, R.; Park, S.Y.; Yang, Y.; Gamage, C.D.B.; Son, Y.J.; Paik, M.J.; Kim, H. Inflammatory and tumorigenic effects of environmental pollutants found in particulate matter on lung epithelial cells. Toxicol. In Vivo, 2019, 59, 300-311.] by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) in 2013. In fact, butyl benzyl phthalate (BBzP, 1), dibutyl phthalate (DnBP, 5), diethyl phthalate (DEP, 7), diisobutyl phthalate (DiBP, 12), diisononyl phthalate (DINP, 15), di-n-octyl phthalate (DnOP, 20), dipentyl phthalate (DNPP, 9), di-isohexyl phthalate, dicyclohexyl phthalate (DcHP, 11), and di-isoheptyl phthalate have all been associated with illnesses and disorders as diverse as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder [26Hu, D.; Wang, Y.X.; Chen, W.J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.H.; Xiong, L.; Zhu, H.P.; Chen, H.Y.; Peng, S.X.; Wan, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Y.K. Associations of phthalates exposure with attention deficits hyperactivity disorder: A case-control study among Chinese children. Environ. Pollut., 2017, 229, 375-385.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.05.089] [PMID: 28614761] ], breast cancer [27Zuccarello, P.; Oliveri Conti, G.; Cavallaro, F.; Copat, C.; Cristaldi, A.; Fiore, M.; Ferrante, M. Implication of dietary phthalates in breast cancer. A systematic review. Food Chem. Toxicol., 2018, 118, 667-674.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2018.06.011] [PMID: 29886235] ], obesity [28Zhang, Y.; Dong, T.; Hu, W.; Wang, X.; Xu, B.; Lin, Z.; Hofer, T.; Stefanoff, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Xia, Y. Association between exposure to a mixture of phenols, pesticides, and phthalates and obesity: Comparison of three statistical models. Environ. Int., 2019, 123, 325-336.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.076] [PMID: 30557812] ] and type II diabetes [29Duan, Y.; Wang, L.; Han, L.; Wang, B.; Sun, H.; Chen, L.; Zhu, L.; Luo, Y. Exposure to phthalates in patients with diabetes and its association with oxidative stress, adiponectin, and inflammatory cytokines. Environ. Int., 2017, 109, 53-63.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.09.002] [PMID: 28938100] ], neurodevelopmental issues [30Lopez-Carrillo, L.; Cebrian, M.E. Cognitive function.Effects of Persistent and Bioactive Organic Pollutants on Human Health., 2013, 400-420.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781118679654.ch15] ], behavioral issues, autism spectrum disorders [31Shin, H.M.; Schmidt, R.J.; Tancredi, D.; Barkoski, J.; Ozonoff, S.; Bennett, D.H.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Prenatal exposure to phthalates and autism spectrum disorder in the MARBLES study. Environ. Health, 2018, 17(1), 85.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0428-4] [PMID: 30518373] ], altered reproductive development [32Singh, A.; Kumar, R.; Singh, J.K. Singh; Tanuja, K.S. Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate induced toxicological effects on reproductive system of female mice mus-musculus. J. Ecophysiol. Occup. Health, 2019, 19, 71-75.] and male fertility issues [33Herr, C.; zur Nieden, A.; Koch, H.M.; Schuppe, H.C.; Fieber, C.; Angerer, J.; Eikmann, T.; Stilianakis, N.I. Urinary di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP)--metabolites and male human markers of reproductive function. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health, 2009, 212(6), 648-653.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2009.08.001] [PMID: 19733116] ]. It must be said, however, that in many instances, insufficient data is available to make irrefutable statements on the health impacts of phthalates. Some of the compounds replacing phthalates fare a little better. These include the increasingly used terephthalates such as di(2-ethylhexyl) terephthalate. In addition, dimethyl terephthalate (DMT, 18) which is a starting material in the production of terephthalate based plasticizers as well as in the production of polyalkyl terephthalates [34Gu, J.D. Microbial colonization of polymeric materials for space applications and mechanisms of biodeterioration: a review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation, 2007, 59, 170-179.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.08.010] , 35Li, J.X.; Gu, J.D.; Pan, L. Transformation of dimethyl phthalate, dimethyl isophthalate and dimethyl terephthalate by Rhodococcus rubber Sa and modeling the processes using the modified Gompertz model. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation, 2005, 55, 223-232.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2004.12.003] ], especially in the synthesis of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polytrimethylene terephthalate (PTT), and polybutylene terephthalate (PBT), is looked at as a potential carcinogen and an irritant to skin, eyes and the respiratory tract. As is the case with many monomers and small-molecule starting materials for polymers, also DMT can be found in small concentrations in the respective polymers (Figs. 4 and 5

and 5 ).

).

1.2. Phthalates in Agricultural Use – Phthalate Content in Soil and Agricultural Produce

There is extensive literature on phthalate content in agricultural produce, whether it be tomatoes grown after biosolids application [36Sablayrolles, C.; Silvestre, J.; Lhoutellier, C.; Montrejaud-Vignoles, M. Phthalates uptake by tomatoes after biosolids application: worst case and operational practice in greenhouse conditions. Fresenius Environ. Bull., 2013, 22, 1061-1069.] or radishes grown with sewage sludge and compost application [37Cai, Q.Y.; Mo, C.H.; Wu, Q.T.; Zeng, Q.Y. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and phthalic acid esters in the soil-radish (Raphanus sativus) system with sewage sludge and compost application. Bioresour. Technol., 2008, 99(6), 1830-1836.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2007.03.035] [PMID: 17502135] ]. Extensive developments in analytical chemistry have led to reliable measurement methods for phthalate contents in different types of produce [38Cao, X.L.; Zhao, W.; Dabeka, R. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) adipate and 20 phthalates in composite food samples from the 2013 Canadian Total Diet Study. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess., 2015, 32(11), 1893-1901.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19440049.2015.1079742] [PMID: 26359692] ] and in processed and packaged foods [39Sannino, A. Development of a gas chromatographic/mass spectrometric method for determination of phthalates in oily foods. J. AOAC Int., 2010, 93(1), 315-322.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jaoac/93.1.315] [PMID: 20334193] , 40Cocchieri, R.A. Occurrence of phthalate esters in Italian packaged foods. J. Food Prot., 1986, 49(4), 265-266.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-49.4.265] [PMID: 30959656] ]. The occurrence of phthalates in agricultural soils around the world [41Gibson, R.; Wang, M.J.; Padgett, E.; Beck, A.J. Analysis of 4-nonylphenols, phthalates, and polychlorinated biphenyls in soils and biosolids. Chemosphere, 2005, 61(9), 1336-1344.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.03.072] [PMID: 15979687] , 42Vikelsøe, J.; Thomsen, M.; Carlsen, L. Phthalates and nonylphenols in profiles of differently dressed soils. Sci. Total Environ., 2002, 296(1-3), 105-116.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(02)00063-3] [PMID: 12398330] ], with many studies originating in China [43Kong, S.; Ji, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, L.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Bai, Z.; Sun, Z. Diversities of phthalate esters in suburban agricultural soils and wasteland soil appeared with urbanization in China. Environ. Pollut., 2012, 170, 161-168.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2012.06.017] [PMID: 22813629] -45Li, K.; Ma, D.; Wu, J.; Chai, C.; Shi, Y. Distribution of phthalate esters in agricultural soil with plastic film mulching in Shandong Peninsula, East China. Chemosphere, 2016, 164, 314-321.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.08.068] [PMID: 27596820] ], has been sufficiently established, where DEHP (9) and DnBP (5) are the most abundant phthalates found. The use of plastic mulching in agriculture is still a widespread technique to suppress weed growth and to contain water needs. While biodegradable polymeric films have been advertised, the by far most often used material is both high and low-density polyethene (LDPE and HDPE). Phthalates are mulch PE additives, where it has been shown that these phthalates are released partially into the soil [46Steinmetz, Z.; Wollmann, C.; Schaefer, M.; Buchmann, C.; David, J.; Tröger, J.; Muñoz, K.; Frör, O.; Schaumann, G.E. Plastic mulching in agriculture. Trading short-term agronomic benefits for long-term soil degradation? Sci. Total Environ., 2016, 550, 690-705.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.01.153] [PMID: 26849333] ]. The delivery of phthalates from the plastic film covers of the agricultural plants themselves has been studied in some detail [47Wang, K.; Song, N.; Cui, M.; Shi, Y. Phthalate esters migration from two kinds of plastic films and the enrichment in peanut plant. Fresenius Environ. Bull., 2017, 26, 4409-4415.]. In addition, sewage sludge [42Vikelsøe, J.; Thomsen, M.; Carlsen, L. Phthalates and nonylphenols in profiles of differently dressed soils. Sci. Total Environ., 2002, 296(1-3), 105-116.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(02)00063-3] [PMID: 12398330] ], agrochemicals [48Fernández, M.A.; Gómara, B.; González, M.J. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry, 2012, , 337-374.], wastewater irrigation [49Zhang, Y.; Liang, Q.; Gao, R.; Hou, H.; Tan, W.; He, X.; Zhang, H.; Yu, M.; Ma, L.; Xi, B.; Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Xi, B.; Wang, X. Contamination of phthalate esters (PAEs) in typical wastewater-irrigated agricultural soils in Hebei, North China. PLoS One, 2015, 10(9)e0137998

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137998] [PMID: 26360905] ] and the atmosphere [50Ligocki, M.P.; Leuenberger, C.; Pankow, J.F. Trace organic compounds in rain—II. Gas scavenging of neutral organic compounds. Atmos. Environ., 1985, 19, 1609-1617.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(85)90213-6] , 51Ligocki, M.P.; Leuenberger, C.; Pankow, J.F. Trace organic compounds in rain—III. Particle scavenging of neutral organic compounds. Atmos. Environ., 1985, 19, 1619-1626.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(85)90214-8] ] itself deliver phthalates to the soil [52Hongjun, Y.; Wenjun, X.; Qing, L.; Jingtao, L.; Hongwen, Y.; Zhaohua, L. Distribution of phthalate esters in topsoil: a case study in the Yellow River Delta. China. Environ. Monit. Assess., 2013, 185, 8489-8500.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10661-013-3190-7] [PMID: 23609921] -54He, L.; Gielen, G.; Bolan, N.S.; Zhang, X.; Qin, H.; Huang, H.; Wang, H. Contamination and remediation of phthalic acid esters in agricultural soils in China: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev., 2014, 35, 519-534.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13593-014-0270-1] ]. Especially, the phthalate uptake of plants from sludge has been a worry [55Gonzalez-Villa, F.J.; Saiz-Jimenez, C.; Martin, F. Identification of free organic chemicals found in composted municipal refuse. J. Environ. Qual., 1982, 11, 251-254.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.2134/jeq1982.00472425001100020021x] ], where Shea et al. [56Shea, P.J.; Weber, J.B.; Overcash, M.R. Uptake and phytotoxicity of di-n-butyl phthalate in corn (Zea mays). Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol., 1982, 29(2), 153-158.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01606143] [PMID: 7126902] ] reported a di-n-butyl phthalate (DnBP, 5) uptake in corn at 0.32 ppm from soil contaminated with 100 ppm DnBP (5). The removal of phthalates from agricultural crop derived extracts designated for food or pharmaceutical use is sometimes seen as a necessity and different processes have been developed to that regard [57Yi, N.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, Y. (Hunan Zhongmao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) Method for removing plasticizer from plant-derived flavonoid extract CN 109320561, 2019.].

Phthalates can be cleaved to monophthalates and to phthalic acid by UV light [58Hankett, J.M.; Collin, W.R.; Chen, Z. Molecular structural changes of plasticized PVC after UV light exposure. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2013, 117(50), 16336-16344.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jp409254y] [PMID: 24283894] ], but this is a slow process, at least in water with photochemical half-lives of over 100 days (for butyl benzyl phthalate, 1), 3 years (for dimethyl phthalate, 17) and 1000 years [for bis(ethylhexyl)phthalate, 9] [59Gledhill, W.E.; Kaley, R.G.; Adams, W.J.; Hicks, O.; Michael, P.R.; Saeger, V.W.; Leblanc, G.A. An environmental safety assessment of butyl benzyl phthalate. Environ. Sci. Technol., 1980, 14(3), 301-305.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/es60163a001] [PMID: 22276719] , 60Staples, C.A.; Peterson, D.R.; Parkerton, T.F.; Adams, W.J. The environmental fate of phthalates esters: a literature review. Chemosphere, 1997, 35, 667-749.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0045-6535(97)00195-1] ]. However, as the phthalates penetrate the soil, the degradation pathway open to them is the aerobic or anaerobic ester hydrolysis with subsequent cleavage of the aromatic ring system [61Cartwright, C.D.; Thompson, I.P.; Burns, R.G. Degradation and impact of phthalate plasticizers on soil microbial communities. Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 2000, 19, 1253-1261.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620190506] , 62Nallii, S.; Cooper, D.G.; Nicell, J.A. Biodegradation of plasticizers by Rhodococcus rhodochrous. Biodegradation, 2002, 13(5), 343-352.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1022313810852] [PMID: 12688586] ]. Short-chain phthalates such as diethyl phthalate (DEP, 7) are degraded more easily by microorganisms than longer chain phthalates such as bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP, 9), which can only be co-metabolically degraded in the presence of an additional carbon source [61Cartwright, C.D.; Thompson, I.P.; Burns, R.G. Degradation and impact of phthalate plasticizers on soil microbial communities. Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 2000, 19, 1253-1261.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620190506] , 62Nallii, S.; Cooper, D.G.; Nicell, J.A. Biodegradation of plasticizers by Rhodococcus rhodochrous. Biodegradation, 2002, 13(5), 343-352.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1022313810852] [PMID: 12688586] ]. Different microbial strains have been isolated and used to remove phthalates from different matrices, such as natural water (sea water [63Paluselli, A.; Fauvelle, V.; Galgani, F.; Sempéré, R. Phthalate release from plastic fragments and degradation in seawater. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2019, 53(1), 166-175.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b05083] [PMID: 30479129] ]:), soils [64Carrara, S.M.; Morita, D.M.; Boscov, M.E. Biodegradation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate in a typical tropical soil. J. Hazard. Mater., 2011, 197, 40-48.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.09.058] [PMID: 22014440] ], sediments [65Chang, B.V.; Liao, C.S.; Yuan, S.Y. Anaerobic degradation of diethyl phthalate, di-n-butyl phthalate, and di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate from river sediment in Taiwan. Chemosphere, 2005, 58(11), 1601-1607.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.11.031] [PMID: 15694480] ], wastewater [66Camacho-Munoz, G.A.; Llanos, C.H.; Berger, P.A.; Miosso, C.J.; da Rocha, A.F. Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds in wastewater and sludge from wastewater treatment plants: removal and ecotoxicological impact of wastewater discharges and sludge disposal. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc., 2012, •••, 6508-6513.], and landfills [67Boonyaroj, V.; Chiemchaisri, C.; Chiemchaisri, W.; Yamamoto, K. Removal of organic micro-pollutants from solid waste landfill leachate in membrane bioreactor operated without excess sludge discharge. Water Sci. Technol., 2012, 66(8), 1774-1780.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.2166/wst.2012.324] [PMID: 22907464] ]. A recent review of the microbial degradation of phthalates is available [6Boll, M.; Geiger, R.; Junghare, M.; Schink, B. Microbial degradation of phthalates: biochemistry and environmental implications. Environ. Microbiol. Rep., 2020, 12(1), 3-15.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.12787] [PMID: 31364812] ].

1.3. Phthalates in Aquatic Environments and Isolated from Marine Produce

Monitoring phthalate concentrations in aquatic environments and in marine products has been going on for a long time. A study from Japan, compares the phthalate level of fish caught in the Uji river in 1973 [68Kamata, I.; Tsutsui, G.; Takana, J.; Shirai, T. Phthalic acid esters in fish in the Uji river, Kyoto-fu. Eisei Kogai Kenkyusho Nenpo, 1977, 22, 114-116.] with fish caught there in 1946! A report from 1986 tells us that in the upper Pickwick reservoirs in north Alabama, USA, phthalates have been found to an appreciable degree in turtles, but not in fish or clams [69Dycus, D.L. Technical report series: North Alabama water quality assessment Contaminants in biota, 1986, 7(TVA/ONRED/AWR-86/33) Order No. DE87900603.].

|

Fig. (4) Isophthalates 46-48, dinonyl cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylate isomer (44), and trimellitate 45 as substi-tutes for phthalates as plasticizers. |

|

Fig. (5) Dialkyl alkanedioates and alkenedioates 49, 51, 52, and 56, trialkyl phosphates 55 and cyclosiloxanes 53 and 54, compounds that often accompany phthalates from natural sources. |

A study from Portland, Maine, of 1983 tells us the concentration of dibutyl phthalate (5) and di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (9) in clams were less than those measured in the sediment [70Ray, L.E.; Murray, H.E.; Giam, C.S. Organic pollutants in marine samples from Portland, Maine. Chemosphere, 1983, 12, 1031-1038.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0045-6535(83)90255-2] ]. A Chinese study from 2003 looked at the concentration of dibutyl phthalate (5), diethyl phthalate (7) and di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (9) in water, soil, sediments, and aquatic organisms, including shrimps, fish and clams from Shanghai, Hangzhou Bay, the Grand Canal and surrounding areas [71Zhang, Y.H.; Chen, B.H.; Zheng, L.X. Determination of phthalates in environmental samples. Huanjing Yu Jiankang Zazhi, 2003, 20, 283-286.]. The presence of phthalates in sponges has been explained to have potentially originated from bacteria on the sponges [72Wahidullah, S.; Naik, B.G.; Al-Fadhli, A.A. Chemotaxonomic study of the demosponge Cinachyrella cavernosa (Lamarck). Biochem. Syst. Ecol., 2015, 58, 91-96.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bse.2014.11.001] ].

Meanwhile, there is also beginning to be a good overview of phthalate concentrations in the aquatic environment in different parts of the world, whether it is in the German Bight [73Xie, Z.; Ebinghaus, R.; Temme, C.; Lohmann, R.; Caba, A.; Ruck, W. Atmospheric concentrations and air–sea exchanges of phthalates in the North Sea (German Bight). Atmos. Environ., 2005, 39, 3209-3219.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.02.021] ], the Bay of Marseille [74Paluselli, A.; Fauvelle, V.; Schmidt, N.; Galgani, F.; Net, S.; Sempéré, R. Distribution of phthalates in Marseille Bay (NW Mediterranean Sea). Sci. Total Environ., 2018, 621, 578-587.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.306] [PMID: 29195205] ], or the Asan lake in S.-Korea [75Lee, Y.M.; Lee, J.E.; Choe, W.; Kim, T.; Lee, J.Y.; Kho, Y.; Choi, K.; Zoh, K.D. Distribution of phthalate esters in air, water, sediments, and fish in the Asan Lake of Korea. Environ. Int., 2019, 126, 635-643.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.02.059] [PMID: 30856451] ]. In addition, the mobility of phthalates and their movement between the atmosphere and water [73Xie, Z.; Ebinghaus, R.; Temme, C.; Lohmann, R.; Caba, A.; Ruck, W. Atmospheric concentrations and air–sea exchanges of phthalates in the North Sea (German Bight). Atmos. Environ., 2005, 39, 3209-3219.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.02.021] , 76Xie, Z.; Ebinghaus, R.; Temme, C.; Lohmann, R.; Caba, A.; Ruck, W. Occurrence and air-sea exchange of phthalates in the Arctic. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2007, 41(13), 4555-4560.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/es0630240] [PMID: 17695896] ] or between sediments and water become more understood. Investigations were carried out with deuterated di-n-octylphthalate to better comprehend the uptake of phthalates by mollusks from sediments [77Foster, G.D.; Baksi, S.M.; Means, J.C. Bioaccumulation of trace organic contaminants from sediment by Baltic clams (Macoma balthica) and soft-shell clams (Mya arenaria). Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 1987, 6, 969-976.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620061209] ].

Phthalates in marine produce are watched carefully. Thus, phthalate concentrations have been assessed and monitored in commercial marine pelagic fish species such as Atlantic bluefin tuna from Sardinia [9-14.62 ng/g DEHP (9); 15.-6.3 ng/g MEHP] [78Guerranti, C.; Cau, A.; Renzi, M.; Badini, S.; Grazioli, E.; Perra, G.; Focardi, S.E. Phthalates and perfluorinated alkylated substances in Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) specimens from Mediterranean Sea (Sardinia, Italy): Levels and risks for human consumption. J. Environ. Sci. Health B, 2016, 51(10), 661-667.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03601234.2016.1191886] [PMID: 27323803] ], Atlantic herring, Atlantic mackerel [17-27 μg/g DIHP (14)] [79Musial, C.J.; Uthe, J.; Sirota, G.R.; Burns, B.G.; Gilgan, M.W.; Zitko, V.; Matheson, R.A. Di-n-hexyl phthalate (DHP), a newly identified contaminant in Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus harengus) and Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 1981, •••, 856-859.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/f81-113] ], Baltic herring [5.6 μg/g DMP (17)] and codfish [1.9 μg/g DMP (17)] [80Ostrovsky, I.; Čabala, R.; Kubinec, R.; Górová, R.; Blaško, J.; Kubincová, J.; Řimnáčová, L.; Lorenz, W. Determination of phthalate sum in fatty food by gas chromatography. Food Chem., 2011, 124, 392-395.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.06.045] ]. Phthalate concentrations have also been measured in farmed fish such as in common carp [0.26 mg/kg – 0.72 mg/kg DEHP (9), 0.31 mg/kg - 0.56 mg/kg DnBP, (5)] [81Jarašová, A.; Puškárová, L.; Di Stancová, V. -2-ethylhexyl phthalate and di-n-butyl phthalate in tissues of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) after harvest and after storage in fish storage tank. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci., 2012, 1, 277-286.]. How all this translates to exposure of humans to phthalates is an issue of major concern. Already in 1973, D. Williams noted levels of dibutyl phthalate [5, 0-78 ppm] and di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate [0-160 ppb] in 21 samples of fish available to the Canadian consumer [82Williams, D.T. Dibutyl- and di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate in fish. J. Agric. Food Chem., 1973, 21(6), 1128-1129.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf60190a028] [PMID: 4755838] ]. Since then, a number of studies have looked into the risk of human contact to phthalates through consumption of different types of produce [83Servaes, K.; Van Holderbeke, M.; Geerts, L.; Sioen, I.; Fierens, T.; Voorspels, S.; Vanermen, G. Phthalate contamination in food: occurrence on the Belgian market and possible contamination pathways. Organohalogen Compd., 2011, 73, 291-294.-86Cheng, Z.; Nie, X.P.; Wang, H.S.; Wong, M.H. Risk assessments of human exposure to bioaccessible phthalate esters through market fish consumption. Environ. Int., 2013, 57-58, 75-80.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2013.04.005] [PMID: 23688402] ], be it in Belgian, UK, Tunisian or Chinese markets. Overviews of phthalates in food have been published [87Cao, X.L. Phthalate esters in foods: sources, occurrence, and analytical methods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf., 2010, 9(1), 21-43.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-4337.2009.00093.x] [PMID: 33467808] ].

1.4. Phthalates Isolated from Organisms as Natural Products – Isolation of Phthalate Replacement Products from Organisms

Against this background, there is a large body of literature concerning the isolation of phthalates from organisms as natural products, i.e., not as or not expressly as contaminants found within the organisms (Table 2). In a number of papers listed here, though, the connection is made between phthalates and plasticizers [88Jeevitha, T.; Deepa, K.; Michael, A. In vitro study on the anti-microbial efficacy of Aloe vera against Candida albicans. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res., 2018, 12, 930-937.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.5897/AJMR2015.7631] ], although it is not precisely noted that the phthalates isolated from the organisms are true of anthropogenic nature. In certain cases, it was not relevant for the authors whether the isolated phthalates were actual plant metabolites or anthropogenic contaminants, such as in the case of identifying the volatile components that make up the bouquet of pineapples of different degrees of ripeness [89Umano, K.; Hagi, Y.; Nakahara, K.; Shoji, A.; Shibamoto, T. Volatile constituents of green and ripened pineapple (Ananas comosus [L.] Merr.). J. Agric. Food Chem., 1992, 40, 599-603.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00016a014] ], where both dibutyl phthalate (5) and diisobutyl phthalate (12) were found; or in the case of identifying the flavor components of clams and mussels such as from the Hongdao clam [90Lan, X.; Xue, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y. Aromatic components of Hongdao clam by HS-SPME and GC-MS. Adv. Mat. Res. (Durnten-Zurich), 2013, 709, 49-52.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.709.49] ], where dibutyl phthalate (5) and diethyl phthalate were isolated, or from the muscles of four other Chinese sea clams, where dibutyl phthalate (5) and butyl benzyl phthalate (1) were isolated [91Liu, J.; Lu, B.T.; Xiao, S.Y. Analysis and evaluation of flavor substances in four sea clam muscles. Huanjing Yu Jiankang Zazhi, 2008, 25, 633-634.]. In other cases, the authors were very much aware of the possibility of the isolated phthalate being a contaminant. Thus, Silva at al. [92Silva, F.A.; Liotti, R.G.; Boleti, A.P.A.; Reis, É.M.; Passos, M.B.S.; Dos Santos, E.L.; Sampaio, O.M.; Januário, A.H.; Branco, C.L.B.; Silva, G.F.D.; Mendonça, E.A.F.; Soares, M.A. Diversity of cultivable fungal endophytes in Paullinia cupana (Mart.) Ducke and bioactivity of their secondary metabolites. PLoS One, 2018, 13(4)e0195874

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195874] [PMID: 29649297] ]. were clearly aware that DEHP (9) could be a contaminant from laboratory equipment and state that DEHP (9) was only isolated from Diaporthe phaseolorum and not from other organisms that they worked with under identical conditions. S. E. McKenzie et al. isolated bis (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate from the marine fungus Corollospora lacera, but showed that the compound was indeed an artifact stemming from the culturing and extraction process [93MacKenzie, S.E.; Gurusamy, G.S.; Piórko, A.; Strongman, D.B.; Hu, T.; Wright, J.L.C. Isolation of sterols from the marine fungus Corollospora lacera. Can. J. Microbiol., 2004, 50(12), 1069-1072.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/w04-103] [PMID: 15714238] ]. Laboratory contamination with phthalates can happen facilely as the author has also experienced in his laboratory, once both in Japan and in the United Arab Emirates. Typical sources of contamination are solvent bottles made of plastic and cling films. Sources, incidents and remedies of such contaminations have been reviewed by Nguyen et al. [94Nguyen, D.H.; Nguyen, D.T.M.; Kim, E.K. Effects of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) released from laboratory equipments. Korean J. Chem. Eng., 2008, 25, 1136-1139.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11814-008-0186-z] ] and Reid et al. [95Reid, A.M.; Brougham, C.A.; Fogarty, A.M.; Roche, J.J. An investigation into possible sources of phthalate contamination in the environmental analytical laboratory. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem., 2007, 87, 125-133.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03067310601071183] ]. Nevertheless, the overwhelming number of reports on the isolation of phthalates from natural organisms originate from the exposure of these organisms to anthropogenic environmental pollution rather than from contamination of the samples in the laboratory. Oftentimes, phthalates are isolated as a bouquet of different phthalates from the organisms [96Yang, T.; Zhang, C.X.; Cai, E.B.; Bao, J.C.; Zheng, Y.L. Analysis of chemical composition of volatile oil from underground part of Astilbe chinensis (Maxim.) Franch.et Sav using GC – MS. Ziyuan Kaifa Yu Shichang, 2011, 27, 106-107.-98Qin, L.Q.; Liu, X.X.; Luo, S.Y.; Yang, D. GC-MS comparative analysis of low-polarity compounds of Amaranthus caudatus L. Anhui Nongye Kexue, 2015, 43, 81-83.], often hand-in-hand with alkanedioates such as diisobutyl oxalate (51) and diisobutyl succinate (52) in addition to siloxanes such as hexadecamethylcyclooctasiloxane (53) and octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (54) that all are known additives in polymers [96Yang, T.; Zhang, C.X.; Cai, E.B.; Bao, J.C.; Zheng, Y.L. Analysis of chemical composition of volatile oil from underground part of Astilbe chinensis (Maxim.) Franch.et Sav using GC – MS. Ziyuan Kaifa Yu Shichang, 2011, 27, 106-107.]. From the fruits of Acanthopanax sessiliflorus (Araliaceae), 13 different phthalates were isolated [99Asilbekova, D.T.; Gusakova, S.D.; Glushenkova, A.I. Lipids in fruits of Acanthopanax sessiliflorus., 1985, , 760-766.]. In 2020, N. Kumari et al. published the isolation of dibutyl phthalate (5) as secondary metabolites of an actinomycetes strain grown on actinomycete isolation agar. However, in the same study tert-butylcalix [4Huang, J.; Nkrumah, P.N.; Li, Y.; Appiah-Sefah, G. Chemical behavior of phthalates under abiotic conditions in landfills. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol., 2013, 224, 39-52.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5882-1_2] [PMID: 23232918] ] arene, clearly, a synthetic product, was also found as a purported secondary metabolite of the actinomycetes strain [100Kumari, N.; Menghani, E.; Mithal, R. GCMS analysis & assessment of antimicrobial potential of rhizospheric Actinomycetes of AIA3 isolate. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl., 2020, 19, 111-119.].

Most of the time, the structures of the phthalates were determined by GC-MS, relying on the retention time of the compounds on the specific column material used and the mass spectrometric data as analyzed by a computer-accessible database. While mostly the data analysis is expected to be correct, such an analysis is not without its danger. Furthermore, isomeric structures, especially of long-chain esters, which in the case of the phthalates are known to be produced industrially oftentimes as isomeric mixtures, are not easily distinguished and need human aided analysis, with multiple mass spectrometric analyses carried out under different conditions. In a number of cases, there is a mismatch between reported and accepted physical data of the phthalates. Thus, DEHP (9) has been isolated from Diaporthe phaseolorum as a dark yellow solid but resembles a colorless oil [92Silva, F.A.; Liotti, R.G.; Boleti, A.P.A.; Reis, É.M.; Passos, M.B.S.; Dos Santos, E.L.; Sampaio, O.M.; Januário, A.H.; Branco, C.L.B.; Silva, G.F.D.; Mendonça, E.A.F.; Soares, M.A. Diversity of cultivable fungal endophytes in Paullinia cupana (Mart.) Ducke and bioactivity of their secondary metabolites. PLoS One, 2018, 13(4)e0195874

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195874] [PMID: 29649297] ]. Similarly, di-n-butyl phthalate (5), isolated as a secondary metabolite of an endophytic fungal strain of Rumex madaio, has been reported as a solid, although again, the compound is a colorless oil at room temperature [101Bai, X.L.; Yu, R.L.; Li, M.Z.; Zhang, H.W. Antimicrobial assay of endophytic fungi from Rumex madaio and chemical study of strain R1. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol., 2019, 14, 129-135.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.3329/bjp.v14i3.41598] ]. In many cases, however, extensive NMR spectroscopic analyses bear out the structures of the compounds perfectly.

Dialkyl phthalates are initially metabolized to monoalkyl phthalates by a number of microorganisms [104Eaton, R.W.; Ribbons, D.W. Metabolism of dibutylphthalate and phthalate by Micrococcus sp. strain 12B. J. Bacteriol., 1982, 151(1), 48-57.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.151.1.48-57.1982] [PMID: 7085570] ], and it has been realized that in the digestive lumen and liver of fish, monoalkyl phthalates (MPA) may also be produced from dialkyl phthalates [105Fourgous, C.; Chevreuil, M.; Alliot, F.; Amilhat, E.; Faliex, E.; Paris-Palacios, S.; Teil, M.J.; Goutte, A. Phthalate metabolites in the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) from Mediterranean coastal lagoons. Sci. Total Environ., 2016, 569-570, 1053-1059.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.159] [PMID: 27412480] ]. This leads to 913 ± 885 ng/g MPA in European eel (Anguilla anguilla) muscles, collected in two French lagoons in the Mediterranean Sea [105Fourgous, C.; Chevreuil, M.; Alliot, F.; Amilhat, E.; Faliex, E.; Paris-Palacios, S.; Teil, M.J.; Goutte, A. Phthalate metabolites in the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) from Mediterranean coastal lagoons. Sci. Total Environ., 2016, 569-570, 1053-1059.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.159] [PMID: 27412480] ], to 0.54 ng/g for benzyl phthalate (MBzP, 24) to 82 ng/g for n-butyl phthalate (MnBP, 25) in the muscles of juvenile Shiner Perch (Cymatogaster aggregata) [106McConnell, M.L. Distribution of phthalate monoesters in an aquatic food web. Master Report No. 426. School of Resource and Environmental Management, Simon Frazer University, 2007.] and to 0.24–1.1 ng/g for ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP, 26, 6.63–60.9 ng/g for MnBP (25) in the white-spotted greenling (Hexagrammos stelleri) [107Blair, J.D.; Ikonomou, M.G.; Kelly, B.C.; Surridge, B.; Gobas, F.A. Ultra-trace determination of phthalate ester metabolites in seawater, sediments, and biota from an urbanized marine inlet by LC/ESI-MS/MS. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2009, 43(16), 6262-6268.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/es9013135] [PMID: 19746723] ]. In these cases again, the substrate phthalates will be of anthropogenic origin. Monoalkyl phthalates such as MEHP (26) and MnBP (25) have been isolated from a number of bacteria, algae and fungi, but also from terrestrial plants (Table 2 ). Monoalkyl phthalates are being used as biomarkers for the original presence of dialkyl phthalates in organisms. The question remains in how far certain occurrences of phthalates in natural organisms indicate that they are natural products of these organisms. Table 2 shows a selection of reports of phthalates found in various organisms, especially in plants, bacteria, and fungi that do not specifically mention a possible anthropogenic origin of the phthalates. Of the 26 industrially most produced phthalates, only of diisoundecyl-, diisotridecyl- and of diallyl phthalate (3), no reports could be found regarding their isolation as products from plants. Interestingly, larger phthalates such as diisotridecyl phthalate, which is used in heat-resistant cables, have not been reported from plant isolates, either, yet. On the other hand, it would have been interesting to find the isolation of dialkyl phthalates that are known not to have been synthesized industrially. This data is hard to come by. Thus, it has been mentioned that one sign that bis(2-methylheptyl) phthalate were produced by Hypericum hyssopifolium (Guttiferae) itself, was that the compound was not used in the chemical industry [102Cakir, A.; Mavi, A.; Yildirim, A.; Duru, M.E.; Harmandar, M.; Kazaz, C. Isolation and characterization of antioxidant phenolic compounds from the aerial parts of Hypericum hyssopifolium L. by activity-guided fractionation. J. Ethnopharmacol., 2003, 87(1), 73-83.

). Monoalkyl phthalates are being used as biomarkers for the original presence of dialkyl phthalates in organisms. The question remains in how far certain occurrences of phthalates in natural organisms indicate that they are natural products of these organisms. Table 2 shows a selection of reports of phthalates found in various organisms, especially in plants, bacteria, and fungi that do not specifically mention a possible anthropogenic origin of the phthalates. Of the 26 industrially most produced phthalates, only of diisoundecyl-, diisotridecyl- and of diallyl phthalate (3), no reports could be found regarding their isolation as products from plants. Interestingly, larger phthalates such as diisotridecyl phthalate, which is used in heat-resistant cables, have not been reported from plant isolates, either, yet. On the other hand, it would have been interesting to find the isolation of dialkyl phthalates that are known not to have been synthesized industrially. This data is hard to come by. Thus, it has been mentioned that one sign that bis(2-methylheptyl) phthalate were produced by Hypericum hyssopifolium (Guttiferae) itself, was that the compound was not used in the chemical industry [102Cakir, A.; Mavi, A.; Yildirim, A.; Duru, M.E.; Harmandar, M.; Kazaz, C. Isolation and characterization of antioxidant phenolic compounds from the aerial parts of Hypericum hyssopifolium L. by activity-guided fractionation. J. Ethnopharmacol., 2003, 87(1), 73-83.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00112-0] [PMID: 12787957] ]. It must be noted, however, that two patents existed for the production and use of the compounds at that time, one by BASF and one by Casio Computer Co [103JP 57063379 (Casio Computer Co.) Guest-host effect liquid crystal display devices, 1982.].

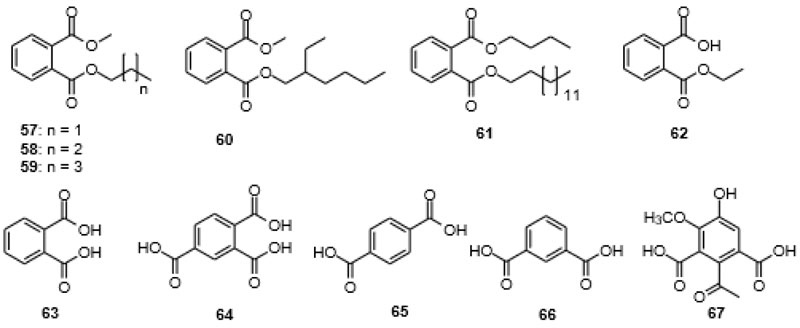

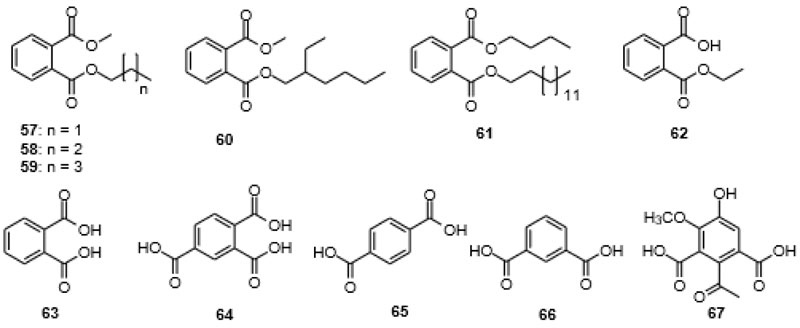

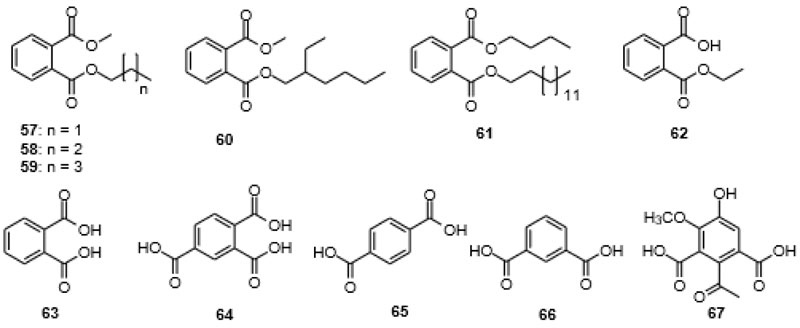

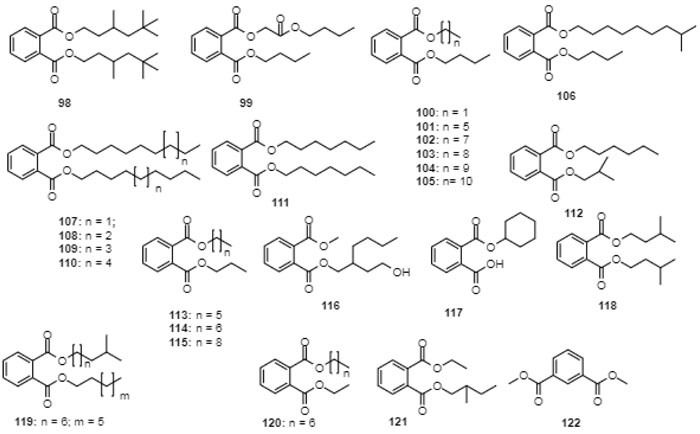

It is interesting to screen the frequency of articles reporting on the isolation of phthalates with one short and one long alkyl chain, which is not that frequently found as additives in consumer products. These would include methyl propyl phthalate (57), n-butyl methyl phthalate (58), methyl n-pentyl phthalate (59), 2-ethylhexyl methyl phthalate (60) and the corresponding alkyl ethyl phthalates (Fig. 6 ). The interesting finding is that quite a few reports of isolation of these “mis-matched”, non-symmetric, less produced phthalates from different organisms exist [108Lucas, E.M.F.; Abreu, L.M.; Marriel, I.E.; Pfenning, L.H.; Takahashi, J.A. Phthalates production from Curvularia senegalensis (Speg.) Subram, a fungal species associated to crops of commercial value. Microbiol. Res., 2008, 163(5), 495-502.

). The interesting finding is that quite a few reports of isolation of these “mis-matched”, non-symmetric, less produced phthalates from different organisms exist [108Lucas, E.M.F.; Abreu, L.M.; Marriel, I.E.; Pfenning, L.H.; Takahashi, J.A. Phthalates production from Curvularia senegalensis (Speg.) Subram, a fungal species associated to crops of commercial value. Microbiol. Res., 2008, 163(5), 495-502.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2007.02.003] [PMID: 17462873] ]. n-Butyl n-tetradecyl phthalate (61) was isolated from the leaves of Urtica dioica L [109Dar, S.A.; Yousuf, A.R.; Ganai, F.A.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, N.; Singh, R. Bioassay guided isolation and identification of anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial compounds from Urtica dioica L. (Urticaceae) leaves. Afr. J. Biotechnol., 2012, 11, 12910-12920.]. together with a number of other compounds of anthropogenic origin such as di-n-butylphthalate (DnBP, 5), di-2-ethylhexylphthalate (DEHP, 9), tributyl phosphate (55), and bis(2-ethylhexyl)maleate (56), all used as plasticizers, sealants or hydraulic fluids. Ethyl methyl phthalate (EMP, 23) was found in the stems of thorn apple [Datura stramonium L.] [110Durak, H.; Aysu, T. Structural analysis of bio-oils from subcritical and supercritical hydrothermal liquefaction of Datura stramonium L. J. Supercrit. Fluids, 2016, 108, 123-135.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2015.10.016] ], in Italian thistle [Carduus pycnocephalus L.] [111Al-Shammari, L.A.; Hassan, W.H.B.; Al-Youssef, H.M. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil and lipid content of Carduus pycnocephalus L. growing in Saudi Arabia. J. Chem. Pharm. Res., 2012, 4, 1281-1287.], and dyer’s woad [Isatis indigotica] [112Wu, J.; Sun, D.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; He, L.; Dong, W. GC-MS analysis of liposoluble constituents in Isatis indigotica. Zhongguo Yaofang, 2008, 19, 2354-2356.], among other plants. Research has shown that primary biodegradation of DEP mostly follows two paths, namely firstly the hydrolysis to monoethyl phthalate (MEP, 62) and then to phthalic acid (PA, 63) and secondly the de-methylation and trans-esterification to form ethyl methyl phthalate (EMP, 23). These pathways have been shown to operate in Pseudomonas sp. DNE-S1 [113Tao, Y.; Li, H.; Gu, J.; Shi, H.; Han, S.; Jiao, Y.; Zhong, G.; Zhang, Q.; Akindolie, M.S.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y. Metabolism of diethyl phthalate (DEP) and identification of degradation intermediates by Pseudomonas sp. DNE-S1. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf., 2019, 173, 411-418.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.02.055] [PMID: 30798184] ] and in Sphingobium yanoikuyae SHJ [114Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Peng, Y.E.; Tong, L.; Feng, L.; Ma, K. New pathways for the biodegradation of diethyl phthalate by Sphingobium yanoikuyae SHJ, Proc. Biochem., 2018, 71, 152-158.]. Enzymatic trans-esterification in natural organisms of industrial phthalates to mixed phthalates should be considered but has not been studied, to the best of the author’s knowledge. Finally, phthalic acid has been found in a number of plant extracts, such as in the ethyl acetate extract of Bridelia ovata [115Poofery, J.; Khaw-on, P.; Subhawa, S.; Sripanidkulchai, B.; Tantraworasin, A.; Saeteng, S.; Siwachat, S. Lertprasertsuke, N.; Banjerdpongchai, R. Potential of Thai herbal extracts on lung cancer treatment by inducing apoptosis and synergizing chemotherapy. Molecules, 2020, 25, 231-261.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/molecules25010231] ] and ethanolic extracts of licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) leaves [116Vijayalakshmi, U.; Shourie, A. Comparative GC-MS analysis of secondary metabolites from leaf, stem and callus of Glycyrrhiza glabra. World J. Pharm. Res., 2019, 8, 1915-1923.], sometimes in concert with phthalates [117Mohan, S.C.; Anand, T. Comparative study of identification of bioactive compounds from Barringtonia acutangula leaves and bark extracts and its biological activity. J. Appl. Sci. (Faisalabad), 2019, 19, 528-536.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.3923/jas.2019.528.536] ]. It must be noted, however, that phthalic acid (63) also can derive from the oxidation of naphthalenes as VOCs in the atmosphere. On the other hand, terephthalic acid (65) (see below) can derive from the burning of plastic, while 1,2,4-benzenetricarboxylic acid (64) can originate from the oxidation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Thus, phthalic acid, as well as terephthalic acid (65) and 1,2,4-benzenetricarboxylic acid (64), have been found residing on PM2.5 in the atmosphere (eg., at a max. of 73.2 ng/m3 collected air space over Nanhai, China; 178.5 ng/m3; and 43.4 ng/m3, respectively) [118He, X.; Huang, X.H.H.; Chow, K.S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Wu, D.; Yu, J.Z. Abundance and sources of phthalic acids, benzene-tricarboxylic acids, and phenolic acids in PM2.5 at urban and suburban sites in Southern China. ACS Earth Space Chem., 2018, 2, 147-158.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.7b00131] ].

As mentioned above, terephthalates, trimellitates and ring-hydrogenated analogs of phthalates, i.e., cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylates, have partially replaced phthalates as plasticizers in recent times, and they have started to appear in the environment in different concentrations. Thus, humans are equally exposed to terephthalates as has been shown in a recent German study on phthalate content in urine samples from 1999 to 2017, which indicated that the human exposure to para-phthalates (terephthalates) continues to grow [119Lessmann, F.; Kolossa-Gehring, M.; Apel, P.; Rüther, M.; Pälmke, C.; Harth, V.; Brüning, T.; Koch, H.M. German Environmental Specimen Bank: 24-hour urine samples from 1999 to 2017 reveal rapid increase in exposure to the para-phthalate plasticizer di(2-ethylhexyl) terephthalate (DEHTP). Environ. Int., 2019, 132105102

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105102] [PMID: 31491609] ] as these are replacing the phthalates as less regulated plasticizers. Here, the author tried to find whether this is also reflected in their isolation from natural sources. Indeed, reports on the isolation of terephthalates, especially from plant sources, could be found (Table 3), as could be on the isolation of isophthalates (dialkyl 1,3-phthalates, Table 4). Isophthalates in the form of ethylene terephthalate-isophthalate copolymers have been used in food packaging films, but have also been formulated as diluents in polymers such as polyethylene terephthalates [120Zekriardehani, S.; Joshi, A.S.; Jabarin, S.A.; Gidley, D.W.; Coleman, M.R. Effect of dimethyl terephthalate and dimethyl isophthalate on the free volume and barrier properties of poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET): amorphous PET. Macromolecules, 2018, 51, 456-467.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.7b02230] ]. Benzene-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (isophthalic acid, 66) has been isolated from a number of plants. Typical isolations have been reported from the essential oil of Dendrobium nobile [121Huang, X.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Xu, X. Constituents in essential oil of Dendrobium nobile with GC-MS. Shizhen Guoyi Guoyao, 2010, 21, 889-891.], and stems of cultivated Dendrobium officinale, and Dendrobium huoshanense [122Jin, Q.; Jiao, C.; Sun, S.; Cheng, C.; Yongping, L.; Fan, H.; Zhu, Y. Metabolic analysis of medicinal Dendrobium officinale and Dendrobium huoshanense during different growth years. PLoS One, 2016, 11, e0146607/1-e0146607/17.] (Orchidaceae), from the air-dried parts of the whole plant Swertia angustifolia (Gentianaceae) [123He, K.; Cao, T.W.; Wang, H.L.; Geng, C.A.; Zhang, X.M.; Chen, J.J. [Chemical constituents of Swertia angustifolia.]. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi, 2015, 40(18), 3603-3607.

[PMID: 26983208] ], from the leaves of Cerbera manghas (sea mango, Apocynaceae) [124Zhang, X.; Pei, Y.; Liu, M.; Kang, S.; Zhang, J. Organic acids from leaves of Cerbera manghas. Zhongcaoyao, 2010, 41, 1763-1765.], and from the culture filtrate of the yeast Candida tropicalis [125Abbasi, A.; Zaidi, Z.H. Isolation of isophthalic acid from Candida tropicalis. J. Chem. Soc. Pak., 1980, 2, 49-49.]. In addition, ring-substituted isophthalic acids have been found, such as 2-acetyl-5-hydroxy-4-methoxyisophthalic acid (67, Fig. 6 ) in the fungus Talaromyces flavus (Trichocomaceae) [126He, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Mu, Z.; Zou, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhong, G. A new isophthalic acid from Talaromyces flavus. Chem. Nat. Compd., 2017, 53, 409-411.

) in the fungus Talaromyces flavus (Trichocomaceae) [126He, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Mu, Z.; Zou, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhong, G. A new isophthalic acid from Talaromyces flavus. Chem. Nat. Compd., 2017, 53, 409-411.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10600-017-2010-7] ]. Few examples of the isolation of trimellitic acid esters as natural products could be located (Table 4), even though these also had been forwarded as additives to agrochemical powder preparations [127Hokko Chem. Ind., Ltd. Trimellitic acid esters for quality improvement of agrochemical powder preparation JP 57159702, 1982.] such as to fertilizers [128Chen, Y. (P.R.C.) Long-acting slow release fertilizer dedicated for apple CN 104892245, 2015.]. Moreover, to date, no report could be found of the isolation of diisononyl cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylate from a plant or other organism as a natural product.

|

Fig. (6) Non-symmetric phthalates 57-61, ethyl phthalate 62, benzenedicarboxylic and tricarboxylic acids 63-67. |

1.5. Uncommon Phthalates Isolated from Organisms as an Indication that These are Natural Products and not Products of Anthropogenic Origin

2-Methyl-, 2-ethyl, and 2-propylalkyl phthalates such as compounds 9, 21 36, and 43 exhibit stereocenter(s), where it must be noted that industrial phthalates are produced as stereoisomeric mixtures from the racemic alcohols. A number of papers have reported on the isolation of enantiopure or at least enantio-enriched phthalates [129Singh, N.; Mahmood, U.; Kaul, V.K.; Jirovetz, L. A new phthalic acid ester from Ajuga bracteosa. Nat. Prod. Res., 2006, 20(6), 593-597.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14786410500185550] [PMID: 16835093] , 130Afza, N.; Yasmeen, S.; Ferheen, S.; Malik, A.; Ali, M.I.; Kalhoro, M.A.; Ifzal, R. New aromatic esters from Galinsoga parviflora. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res., 2012, 14(5), 424-428.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10286020.2012.657181] [PMID: 22348678] ], indicating the natural origin of these phthalates. In the isolation of bis(2S-methylheptyl) phthalate (S-36) from the evergreen perennial plant Ajuga bracteosa, the authors did not forward any analytical result that indicated that the isolated substance was enantiopure or indeed chiral. The structure presented in the paper is that of the meso form of the compound, (R/S)-bis(2-methylheptyl) phthalate (36) [129Singh, N.; Mahmood, U.; Kaul, V.K.; Jirovetz, L. A new phthalic acid ester from Ajuga bracteosa. Nat. Prod. Res., 2006, 20(6), 593-597.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14786410500185550] [PMID: 16835093] ], but the isolation of the compound could potentially be that of a mixture of stereoisomers. Different is the case of the isolation of bis(2S-methylheptyl) phthalate from Galinsoga parviflora, a herbaceous plant of the Asteraceae family, where the isolated compound shows a specific optical rotation [α]D23 of 193.5° (c = 0.075M, MeOH). Here, the question remains as to whether selective enzymatic hydrolysis of a mixture of bis(2-methylheptyl) phthalate stereoisomers has led to (R/S)-bis(2-methylheptyl) phthalate (36) as the one remaining dialkyl phthalate or whether the phthalate as a whole has been biosynthetically created (Fig. 7 ).

).

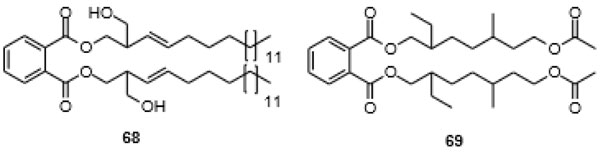

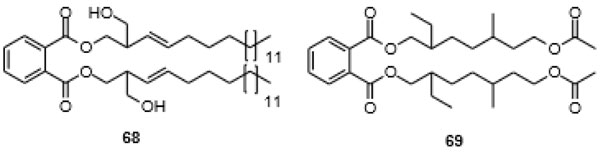

Undoubtedly, there are phthalates that have been isolated from organisms that thus far have had no place in the industry. One such is kurraminate [bis(2-hydroxymethylnonadec-3E-enyl) phthalate] (68) isolated from flowering plant Nepeta kurramensis at Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan [131Ur Rehman, N.; Ahmad, N.; Hussain, J.; Liaqit, A.; Hussain, H.; Bakht, N.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Shinwari, Z.K. One new phthalate derivative from Nepeta kurramensis. Chem. Nat. Compd., 2017, 53, 426-428.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10600-017-2014-3] ], along with known bis(2-ethyleicosyl) phthalate (33), which was also isolated from Phyllanthus muellerianus in West Africa [132Saleem, M.; Nazir, M.; Akhtar, N.; Onocha, P.A.; Riaz, N.; Jabbar, A.; Shaiq Ali, M.; Sultana, N. New phthalates from Phyllanthus muellerianus (Euphorbiaceae). J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res., 2009, 11(11), 974-977.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10286020903341388] [PMID: 20183263] ]. Also, 33 is not produced industrially. Bis(7-acetoxy-2-ethyl-5-methylheptyl) phthalate (69) has been isolated from translucent honeysuckle (Lonicera quinquelocularis). This terminally hydroxylated phthalate, which possesses four stereocenters, not discussed by the authors, again is apparently not of anthropogenic origin [133Khan, D.; Zhao, W.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, S. New antioxidant and cholinesterase inhibitory constituents from Lonicera quinquelocularis. J. Med. Plants Res., 2014, 8, 313-317.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.5897/JMPR2013.5245] , 134Khan, D.; Khan, H.U.; Khan, F.; Khan, S.; Badshah, S.; Khan, A.S.; Samad, A.; Ali, F.; Khan, I.; Muhammad, N. New cholinesterase inhibitory constituents from Lonicera quinquelocularis. PLoS One, 2014, 9(4)e94952

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094952] [PMID: 24733024] ]. The phthalate has been isolated together with the common anthropogenic phthalates DEHP (9) and di-n-octyl phthalate (20). 69 shows an acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) inhibitory activity with IC50 of 1.65 and 5.98 μM.

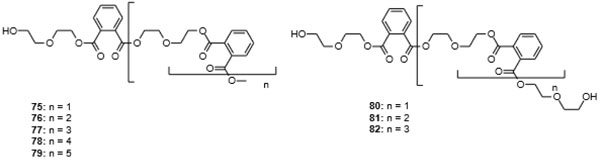

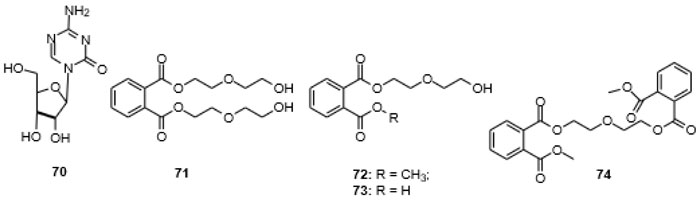

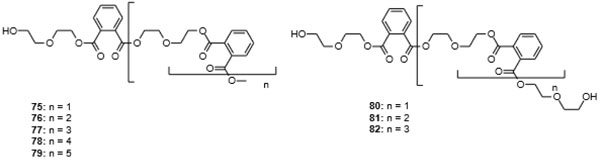

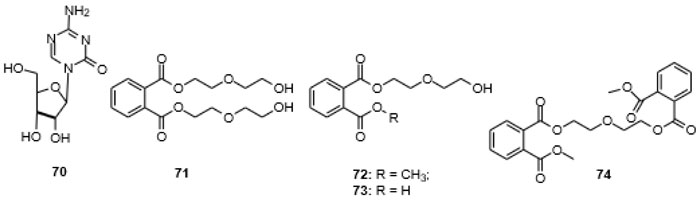

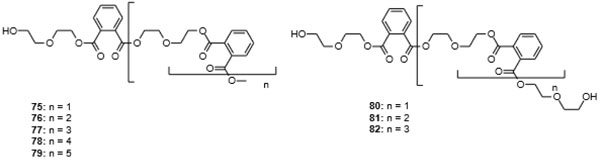

One of the most compelling examples that phthalates can indeed be of natural origin is the isolation of a row of diethylene glycol phthalate ester oligomers from the marine-derived fungus Cochliobolus lunatus [135Chen, M.; Zhang, W.; Shao, C.L.; Chi, Z.M.; Wang, C.Y. DNA methyltransferase inhibitor induced fungal biosynthetic products: Diethylene glycol phthalate ester oligomers from the marine-derived fungus Cochliobolus lunatus. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY), 2016, 18(3), 409-417.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10126-016-9703-y] [PMID: 27245469] ], which was subjected to epigenetic manipulation with the DNA transferase inhibitor 5-azacytidine (70). This led to the isolation of the seven diethylene glycol phthalate esters 72, 75-79, and 82 (Fig. 9 ), in addition to the known compounds 71, 74, 80, and 81 (Figs. 8

), in addition to the known compounds 71, 74, 80, and 81 (Figs. 8 and 9

and 9 ). The compounds have been analyzed by NMR spectroscopic methods, and there is no question as to their identity. The fungus itself was obtained from a piece of fresh tissue from the inner part of the sea anemone Palythoa haddoni, collected from the Weizhou coral reef in the South China Sea [135Chen, M.; Zhang, W.; Shao, C.L.; Chi, Z.M.; Wang, C.Y. DNA methyltransferase inhibitor induced fungal biosynthetic products: Diethylene glycol phthalate ester oligomers from the marine-derived fungus Cochliobolus lunatus. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY), 2016, 18(3), 409-417.

). The compounds have been analyzed by NMR spectroscopic methods, and there is no question as to their identity. The fungus itself was obtained from a piece of fresh tissue from the inner part of the sea anemone Palythoa haddoni, collected from the Weizhou coral reef in the South China Sea [135Chen, M.; Zhang, W.; Shao, C.L.; Chi, Z.M.; Wang, C.Y. DNA methyltransferase inhibitor induced fungal biosynthetic products: Diethylene glycol phthalate ester oligomers from the marine-derived fungus Cochliobolus lunatus. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY), 2016, 18(3), 409-417.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10126-016-9703-y] [PMID: 27245469] ]. The linear polyether motif is not common in nature. The central building block, bis[2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethyl] phthalate (71), as an additive in polyurethanes, however, has been subject to a large number of patents [136Cai, R.; Tu, S. (Suzhou Liansheng Chemistry Co., Ltd.) Nontoxic and odorless dye carrier with good promoting efficacy for polyester fiber and manufacture method CN 107541968, 2016., 137Ikejiri, Y.; Numakura, T.; Tsuchimochi, Y.; Kawakami, K. (Kawasaki Kasei Chemicals, Ltd.) Fluidity improvers, thermoplastic resin compositions, moldings comprising them with good mechanical strength, and their manufacture JP 2007191685 A, 2006.], appearing in patents as early as 1957 [138Patton, T.C.; Hall, F.M. (Baker Castor Oil Co.) Plastigels containing hydroxy fatty acid soaps US Pat. 2794791, 1953.], and of directed synthesis [139Chen, S.; Wang, Q.; Chen, X. Synthesis of phthalic anhydride diglycol ester. Gongye Cuihua, 2008, 16, 45-48.]. [2-(2-Hydroxyethoxy)ethyl] methyl phthalate (72) had not been reported previously, but [2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethyl] phthalate (73) has been covered in a number of patents and also phthalate 74 has appeared in a patent [140Fujii, K.; Ohigashi, T.; Yokoyama, N.; Komehana, N. (Daicel Chemical Industries, Ltd., Japan; Daihachi Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.) Phthalic ester dimers as plasticizers and cellulose fatty acid ester resin compositions JP 11349537 A, 1998.].

A further strong indication that certain phthalates can be of natural origin comes from studies of C.Y. Chen et al., who showed with a 14C inclusion experiment that the red algae Bangia atropurpurea can de novo synthesize DEHP (9) and DnBP (5) [141Chen, C.Y. Biosynthesis of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) and di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) from red alga--Bangia atropurpurea. Water Res., 2004, 38(4), 1014-1018.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2003.11.029] [PMID: 14769421] ]. B. atropurpurea filaments were cultured in a medium containing NaH14CO3. After two weeks, the radioactivity of DEHP (9) and DnBP (5) fractionated by HPLC from cultured filaments was analyzed, where single peak fractions of DEHP (160.00 cpm) and DnBP (4786.67 cpm) were found to have significantly higher radioactivities than the background (28.00 cpm) [141Chen, C.Y. Biosynthesis of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) and di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) from red alga--Bangia atropurpurea. Water Res., 2004, 38(4), 1014-1018.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2003.11.029] [PMID: 14769421] ]. It is not clear, though, whether carbon-14 isotope was built into the structures indiscriminately or whether, for instance, it was only built into the alkyl chain of the esters.

|

Fig. (7) Phthalates 68 and 69, two phthalates that are not produced industrially. |

|

Fig. (8) 5-Azacytidine (70), bis[2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethyl] phthalate (71), [2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethyl] methyl phthalate (72), [2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethyl] phthalate (73) and bis-phthalate 74 [135Chen, M.; Zhang, W.; Shao, C.L.; Chi, Z.M.; Wang, C.Y. DNA methyltransferase inhibitor induced fungal biosynthetic products: Diethylene glycol phthalate ester oligomers from the marine-derived fungus Cochliobolus lunatus. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY), 2016, 18(3), 409-417. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10126-016-9703-y] [PMID: 27245469] ]. |

|

Fig. (9) Diethylene glycol phthalate ester oligomers isolated from the marine-derived fungus Cochliobolus lunatus [135Chen, M.; Zhang, W.; Shao, C.L.; Chi, Z.M.; Wang, C.Y. DNA methyltransferase inhibitor induced fungal biosynthetic products: Diethylene glycol phthalate ester oligomers from the marine-derived fungus Cochliobolus lunatus. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY), 2016, 18(3), 409-417. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10126-016-9703-y] [PMID: 27245469] ]. |

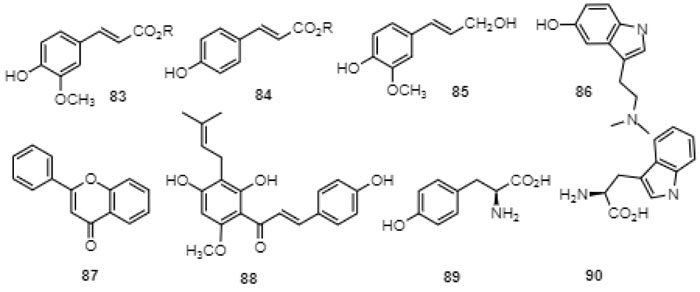

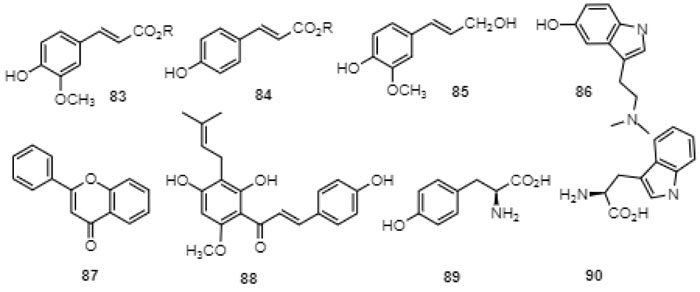

Looking at many of the known biosynthetic pathways involving aromatic structures such as the phenylpropanoid pathway, it is evident that these rarely give rise to aromatic substances with more than one carboxylic acid group substituting the arene unit. In fact, it is very uncommon to find an aromatic natural compound with two electron-withdrawing groups that is not an intermediate. More often than not, electron-donating hydroxyl, alkoxyl or amino groups are in evidence in naturally occurring aromatic compounds such as in the aromatic building blocks of plant lignins in the form of ferulates 83, hydroxycinnamates 84, with coniferyl alcohol (85) as a building block, in aromatic alkaloids such as bufotenin (86), flavonoids such as 2-phenylchromen-4-one (87), chalcones such as xanthohumol (88) and amino acids such tyrosine (89) and tryptophane (90) (Fig. 10 ).

).

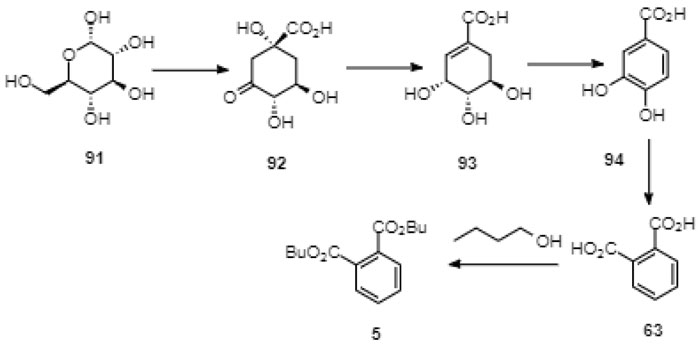

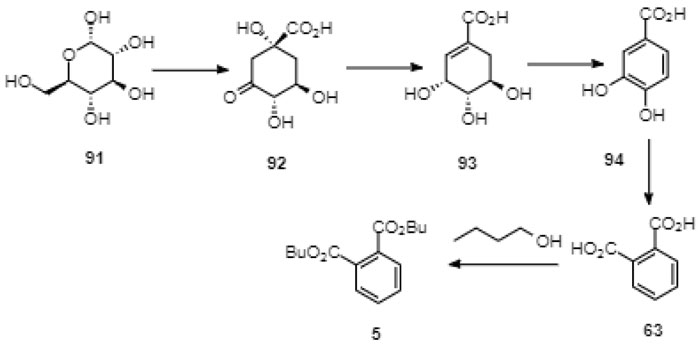

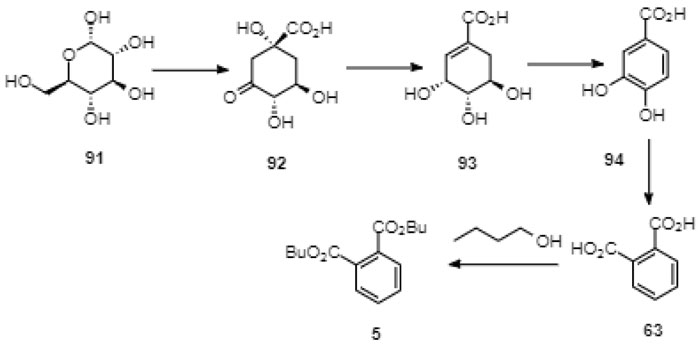

C. Tian et al. showed that DnBP (5) is produced by naturally occurring filamentous fungi Penicillium lanosum PTN121, Trichoderma asperellum PTN7 and Aspergillus niger PTN42, cultured in an artificial medium [142Tian, C.; Ni, J.; Chang, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, N.; Sun, W.; Xie, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Z.; Dang, C.; Huang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Wang, Y. Bio-Source of di-n-butyl phthalate production by filamentous fungi. Sci. Rep., 2016, 6, 19791.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep19791] [PMID: 26857605] ]. Using an enzyme excreted by the fungi, the authors were able to enzymatically produce DnBP (5) under cell-free conditions from D-glucose (91) alone, from D-glucose and 1-butanol, from protocatechuic acid (94) and 1-butanol, and from phthalic acid (63) and 1-butanol (Fig. 11 ). This result indicates that DnBP (5) could be produced by the shikimic acid pathway [142Tian, C.; Ni, J.; Chang, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, N.; Sun, W.; Xie, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Z.; Dang, C.; Huang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Wang, Y. Bio-Source of di-n-butyl phthalate production by filamentous fungi. Sci. Rep., 2016, 6, 19791.

). This result indicates that DnBP (5) could be produced by the shikimic acid pathway [142Tian, C.; Ni, J.; Chang, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, N.; Sun, W.; Xie, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Z.; Dang, C.; Huang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Wang, Y. Bio-Source of di-n-butyl phthalate production by filamentous fungi. Sci. Rep., 2016, 6, 19791.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep19791] [PMID: 26857605] ], although the mechanism of the transformation of protocatechuic acid (94) to phthalic acid (63) is not clear, yet (Figs. 11 -13

-13 ).

).

|

Fig. (10) Typical natural products with an aromatic subunit. |

|

Fig. (11) Proposed pathway from glucose (91) to dibutyl phthalate (5) [142Tian, C.; Ni, J.; Chang, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, N.; Sun, W.; Xie, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Z.; Dang, C.; Huang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Wang, Y. Bio-Source of di-n-butyl phthalate production by filamentous fungi. Sci. Rep., 2016, 6, 19791. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep19791] [PMID: 26857605] ]. |

|

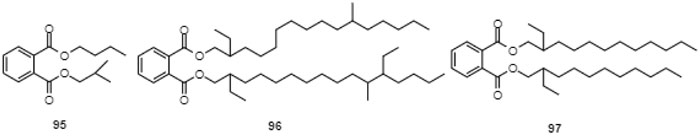

Fig. (12) Butyl isobutyl phthalate (95) and 2,12-diethyl-11-methylhexadecyl 2-ethyl-11-methylhexadecyl phthalate (96) and 2-ethyldecyl 2-ethylundecyl phthalate (97), isolated from the seahorse Hippocampus Kuda Bleeler [152Li, Y.; Qian, Z.J.; Kim, S.K. Cathepsin B inhibitory activities of three new phthalate derivatives isolated from seahorse, Hippocampus Kuda Bleeler. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 2008, 18(23), 6130-6134. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.10.016] [PMID: 18938081] ]. |

|

Fig. (13) Phthalates introduced in the tables. |

1.6. Biological Activities of Phthalates Isolated from Organisms and Comparison to Activities and Hazard Assessment Associated with Industrial Phthalates

The biological assessment carried out on phthalates isolated from plants as potential natural products is quite different from that carried out on phthalates as industrial plasticizers. In the former, phthalates have been screened for their potentially benevolent effects such as antitumour compounds, antimicrobial products and larvicidal agents. In the latter, potential health and environmental risks associated with the compounds have been assessed, also for regulative purposes, which results, for instance, in the testing of these compounds for their hormonal activity. Both of these biological assessment series are nicely complementary.

In many reports of the isolation of phthalates from natural sources, the authors have tested plant extracts containing, apart from the phthalates, a plethora of other components. In these cases, it is difficult to tie the respective biological activity of the extract to the phthalate ingredient. However, there are also a number of reports of testing the biological activity of isolated phthalates collected from natural organisms. In this regard, bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (9) isolated from the flower of Procera gigantea was found to be active against the gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Streptococcus equosemens and Sarcina lutea [143Habib, M.R.; Karim, M.R. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate and anhydrosophoradiol-3-acetate isolated from Calotropis gigantea (Linn.) flower. Mycobiology, 2009, 37(1), 31-36.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.4489/MYCO.2009.37.1.031] [PMID: 23983504] , 144Di El-Sayed, M.H. -(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, a major bioactive metabolite with antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity isolated from the culture filtrate of newly isolated soil Streptomyces (Streptomyces mirabilis strain NSQu-25). World Appl. Sci. J., 2012, 20, 1202-1212.] and against the gram-negative bacteria Closteridium perfringens, Escherchia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Shigella sonnei, Shigella shiga and Shigella dysenteriae [143Habib, M.R.; Karim, M.R. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate and anhydrosophoradiol-3-acetate isolated from Calotropis gigantea (Linn.) flower. Mycobiology, 2009, 37(1), 31-36.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.4489/MYCO.2009.37.1.031] [PMID: 23983504] , 144Di El-Sayed, M.H. -(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, a major bioactive metabolite with antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity isolated from the culture filtrate of newly isolated soil Streptomyces (Streptomyces mirabilis strain NSQu-25). World Appl. Sci. J., 2012, 20, 1202-1212.]. The compound was found to inactive against Bacillus megaterium [143Habib, M.R.; Karim, M.R. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate and anhydrosophoradiol-3-acetate isolated from Calotropis gigantea (Linn.) flower. Mycobiology, 2009, 37(1), 31-36.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.4489/MYCO.2009.37.1.031] [PMID: 23983504] ]. Bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (9) showed activity against the fungus Aspergillus flavus as well. Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium sp. were found to be resistant against the compound [143Habib, M.R.; Karim, M.R. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate and anhydrosophoradiol-3-acetate isolated from Calotropis gigantea (Linn.) flower. Mycobiology, 2009, 37(1), 31-36.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.4489/MYCO.2009.37.1.031] [PMID: 23983504] ]. Not all biological activity tests have led to unanimous results, nevertheless a more detailed compilation of the antimicrobial test results of isolated and purified phthalates from the literature can be found in Table 5.

Both di-n-hexyl phthalate (14) and bis(2-propylheptyl) phthalate (21), isolated from the rhizopheric soil of the tobacco plant, have been found to have allelochemical properties versus lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Also, they showed autotoxic effects on the flue-cured tobacco plant itself [145Ren, X.; He, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Z.; Jin, H.; Li, X.; Qin, B. Isolation, Identification, and Autotoxicity Effect of Allelochemicals from Rhizosphere Soils of Flue-Cured Tobacco. J. Agric. Food Chem., 2015, 63(41), 8975-8980.