- Home

- About Journals

-

Information for Authors/ReviewersEditorial Policies

Publication Fee

Publication Cycle - Process Flowchart

Online Manuscript Submission and Tracking System

Publishing Ethics and Rectitude

Authorship

Author Benefits

Reviewer Guidelines

Guest Editor Guidelines

Peer Review Workflow

Quick Track Option

Copyediting Services

Bentham Open Membership

Bentham Open Advisory Board

Archiving Policies

Fabricating and Stating False Information

Post Publication Discussions and Corrections

Editorial Management

Advertise With Us

Funding Agencies

Rate List

Kudos

General FAQs

Special Fee Waivers and Discounts

- Contact

- Help

- About Us

- Search

The Open Conference Proceedings Journal

(Biological Sciences, Chemical Sciences, Physical Sciences, Medicine, Engineering & Technology)

(Discontinued)

ISSN: 2210-2892 ― Volume 10, 2020

Innovations in Pain Management: Morphine Combined with Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Carlos Horacio Laino*

Abstract

The treatment of acute and chronic severe pain remains a common major challenge faced by clinicians working with the general population, and even after the application of recent advances to treatments, there may still continue to be manifestations of adverse effects.

Chronic pain affects the personal and social life of the patient, and often also their families. In some cases, after an acute pain the patient continues to experience chronic pain, which can be a result of diseases such as cancer.

Morphine is recommended as the first choice opioid in the treatment of moderate to severe acute and chronic pain. However, the development of adverse effects and tolerance to the analgesic effects of morphine often leads to treatment discontinuation.

The present work reviews the different pharmaceutical innovations reported concerning the use of morphine. First, its utilization as the first medication for the treatment of moderate to severe cancer pain and non-cancer pain in patients is evaluated, taking into account the most common complications and adverse effects. Next, strategies utilized to manage these side effects are considered, and we also summarize results using omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid) as a monotherapy or as an adjunct to morphine in the treatment of pain.

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2017Volume: 8

First Page: 52

Last Page: 65

Publisher Id: TOPROCJ-8-52

DOI: 10.2174/221028901708010052

Article History:

Received Date: 02/09/2016Revision Received Date: 05/03/2017

Acceptance Date: 23/03/2017

Electronic publication date: 28/04/2017

Collection year: 2017

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

* Address correspondence to this author the Biotechnology Institute, National University of La Rioja, Argentina Av Luis Vernet y Apostol Felipe. (5000) La Rioja. Argentina, Tel: 011-54-380-466915, Fax: 011-54-380-466915, E-mails: carloslaino25@gmail.com; carloslaino2001@yahoo.ca

| Open Peer Review Details | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Manuscript submitted on 02-09-2016 |

Original Manuscript | Innovations in Pain Management: Morphine Combined with Omega-3 Fatty Acids | |

INTRODUCTION

Pharmaceutical innovation is gradual and can develop in different ways, including through a new drug, a new indication for an existing drug, or a new pharmaceutical formulation to improve the pharmacological profile [1Wertheimer, A.I.; Levy, R.; O’Connor, T.W. Too many drugs? The clinical and economic value of incremental innovations. The clinical and economic value of incremental innovations. In: Investing in Health:, 2001, 14, 77-117. The Social and Economic Benefits of Health Care Innovation 2001

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0194-3960(01)14005-9] ]. Another option for pharmaceutical innovation is a combined treatment with two or more drugs with complementary mechanisms of action, which in fixed-dose combinations can be available in a single tablet [2Wertheimer, A.I.; Morrison, A. Combination Drugs: Innovation in Pharmacotherapy. P&T, 2002, 27, 1.].

In the area of pain, although there is no “perfect analgesic”, scientists can continue to search for compounds with qualities that can approach the “perfect analgesic” by improving the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic aspects of analgesics.

For many years, researchers have been developing new pharmaceutical strategies to help improve the effectiveness of analgesics and prevent or decrease adverse effects by combining these analgesics with a second agent, which may or may not be another analgesic [3Smith, H.S. Combination opioid analgesics. Pain Physician, 2008, 11(2), 201-214.

[PMID: 18354712] ]. This “second non-opioid agent” may be referred to as a “co-analgesic” or “adjuvant analgesic”.

Drug combinations in pain management have been developed for different therapeutic purposes, which can be classified into six categories [3Smith, H.S. Combination opioid analgesics. Pain Physician, 2008, 11(2), 201-214.

[PMID: 18354712] ]: 1) to prolong analgesic duration; 2) to enhance or optimize analgesic efficacy (e.g., analgesic synergy); 3) to prevent or reduce adverse effects; 4) to alleviate opioid effects which are not beneficial (or to enhance beneficial opioid effects); 5) to reduce or prevent opioid tolerance/opioid-induced hyperalgesia; and 6) to prevent dependency issues/addiction potential/craving sensations.

When assessing the usefulness of an adjuvant agent in a particular patient, it is necessary to consider the likelihood of benefits, the risk of adverse effects, facilities for drug administration and patient convenience. However, studies have revealed that there is a great inter-individual variability in the response to adjuvant analgesics, and that for most patients the likelihood of obtaining benefits is limited. Furthermore, many of these adjuvant analgesics have the potential to cause further side effects in addition to the opioid adverse effects, thereby further complicating treatment [4Portenoy, R.K. Adjuvant analgesic agents. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am., 1996, 10(1), 103-119.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70329-4] [PMID: 8821562] ].

1. MORPHINE THERAPY IN CANCER PAIN

The prevalence of cancer has been increasing, with a projection estimated by 2020 of 17 million new cases [5Kanavos, P. The rising burden of cancer in the developing world. Ann. Oncol., 2006, 17(Suppl. 8), i15-, i23.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdl983] [PMID: 16801335] ], which implies that there will be a corresponding increase in individuals with pain caused by the disease and by its treatments [6Paice, J.A. Chronic treatment-related pain in cancer survivors. Pain, 2011, 152(3)(Suppl.), S84-S89.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.010] [PMID: 21036475] ]. In fact, approximately, 50% of patients with cancer already suffer from pain at the time of diagnosis, with about 80% of patients having advanced cancer experiencing moderate to severe pain [7Donnelly, S.; Walsh, D. The symptoms of advanced cancer. Semin. Oncol., 1995, 22(2)(Suppl. 3), 67-72.

[PMID: 7537907] ].

Pain in the patient with cancer is a problem that involves many people, including the patient and family, doctors and nurses, as well as health authorities and medical education bodies, because to some extent we are all affected by the patient’s cancer pain if it is not properly dealt with. Related to this, it is estimated that this pain is not usually well treated with on average only about 30% of patients experiencing a decrease in pain [8Turk, D.C.; Wilson, H.D.; Cahana, A. Treatment of chronic non-cancer pain. Lancet, 2011, 377(9784), 2226-2235.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60402-9] [PMID: 21704872] ].

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of a pain ladder, which is a step-by-step approach for the management of chronic pain based on pain intensity [9Stjernswärd, J. WHO cancer pain relief programme. Cancer Surv., 1988, 7(1), 195-208.

[PMID: 2454740] , 10Bruera, E.; Palmer, J.L.; Bosnjak, S.; Rico, M.A.; Moyano, J.; Sweeney, C.; Strasser, F.; Willey, J.; Bertolino, M.; Mathias, C.; Spruyt, O.; Fisch, M.J. Methadone versus morphine as a first-line strong opioid for cancer pain: a randomized, double-blind study. J. Clin. Oncol., 2004, 22(1), 185-192.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.03.172] [PMID: 14701781] ], and indicates the use of step 3 opioids as a first-line therapy for moderate to severe pain (morphine, methadone, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydromorphone, levorphanol) [11Cancer Pain Relief, 2nd ed; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2015. ], with morphine considered to be the drug of choice for moderate to severe cancer pain sufferers [12McQuay, H. Opioids in pain management. Lancet, 1999, 353(9171), 2229-2232.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03528-X] [PMID: 10393001] ].

2. MORPHINE THERAPY IN NON-CANCER PAIN

In the recent years, some studies have demonstrated an increasing trend in the prescription of opioids for non-cancer patients [13Manchikanti, L.; Singh, A. Therapeutic opioids: a ten-year perspective on the complexities and complications of the escalating use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids. Pain Physician, 2008, 11(2)(Suppl.), S63-S88.

[PMID: 18443641] , 14Thielke, S.M.; Simoni-Wastila, L.; Edlund, M.J.; DeVries, A.; Martin, B.C.; Braden, J.B.; Fan, M.Y.; Sullivan, M.D. Age and sex trends in long-term opioid use in two large American health systems between 2000 and 2005. Pain Med., 2010, 11(2), 248-256.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00740.x] [PMID: 20002323] ]. Although opioid therapy may be appropriate for chronic non-cancer pain in cases where pain is intense, continuous and unresponsive to other analgesic standards, opioids should not be considered a first-line treatment for chronic non-cancer pain in common conditions such as low back pain [15Chou, R.; Huffman, L.H. Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med., 2007, 147(7), 505-514.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00008] [PMID: 17909211] ] and for neuropathic pain [16Eisenberg, E.; McNicol, E.D.; Carr, D.B. Efficacy and safety of opioid agonists in the treatment of neuropathic pain of nonmalignant origin: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA, 2005, 293(24), 3043-3052.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.24.3043] [PMID: 15972567] ].

Despite the benefits of opioids in non-cancer short-term pain, there is insufficient evidence of pain relief without related serious risks, including overdose, dependence, or the addiction to opioids [17Kalso, E.; Edwards, J.E.; Moore, R.A.; McQuay, H.J. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain, 2004, 112(3), 372-380.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.019] [PMID: 15561393] ].

Thus, safe and effective chronic opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain requires clinical skills and knowledge in both the principles of opioid prescribing and in the assessment and management of the risks associated with the use of drugs for non-therapeutic purposes.

3. MORPHINE COMPLICATIONS AND ADVERSE EFFECTS

The side effects of morphine often constitute significant problems in clinical practice, with most patients (up to 80%) with chronic pain having reported having at least one adverse effect resulting from their medication with morphine [18Dumas, E.O.; Pollack, G.M. Opioid tolerance development: a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic perspective. AAPS J., 2008, 10(4), 537-551.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1208/s12248-008-9056-1] [PMID: 18989788] ]. In addition, the presence of vomiting, nausea, constipation, respiratory depression and sedation often limits the dose and efficacy of morphine, potentially leading to the early discontinuation of treatment, under-dosing and inadequate analgesia. Consequently, the identification and appropriate management of these adverse effects could lead to an improvement in treatment adherence, efficacy of morphine and reduced complications.

Morphine toxicity is related to the phenomenon of tolerance and the accumulation of its toxic metabolites. One of the challenges when starting a treatment with morphine is maintaining the analgesic efficacy over time, as both acute and chronic administration of morphine may produce tolerance, which is manifested over time in a reduction in the analgesic effect at the same dose and thus the need for an increased dose to obtain the same efficacy [19Franklin, GM Opioids for chronic noncancer pain A position paper of the American Academy of Neurology, 2014.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000839] ].

The mechanisms underlying the phenomenon of tolerance are not entirely clear. However, recent evidence has suggested the involvement of spinal cord adaptations to pain, with the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), substance P and metabolites derived from arachidonic acid, such as prostaglandins (such as prostaglandin E2) and lipoxygenase (LOX) metabolites, playing a very important role [20Trang, T.; Quirion, R.; Jhamandas, K. The spinal basis of opioid tolerance and physical dependence: Involvement of calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P, and arachidonic acid-derived metabolites. Peptides, 2005, 26(8), 1346-1355.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.031] [PMID: 16042975] , 21Smith, H.S. Opioid metabolism. Mayo Clin. Proc., 2009, 84(7), 613-624.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60750-7] [PMID: 19567715] ].

CGRP is a pronociceptive transmitter at the spinal level and it is released centrally from nociceptive fibers in response to noxious stimuli [22Biella, G.; Panara, C.; Pecile, A.; Sotgiu, M.L. Facilitatory role of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) on excitation induced by substance P (SP) and noxious stimuli in rat spinal dorsal horn neurons. An iontophoretic study in vivo. Brain Res., 1991, 559(2), 352-356.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(91)90024-P] [PMID: 1724408] , 23Cridland, R.A.; Henry, J.L. Intrathecal administration of CGRP in the rat attenuates a facilitation of the tail flick reflex induced by either substance P or noxious cutaneous stimulation. Neurosci. Lett., 1989, 102(2-3), 241-246.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-3940(89)90085-2] [PMID: 2478930] ]. Chronic morphine administration produces an adaptive increase in the release of spinal CGRP, in response to a sustained opioid exposure, and finally contributes to the initiation and maintenance of morphine-induced tolerance [20Trang, T.; Quirion, R.; Jhamandas, K. The spinal basis of opioid tolerance and physical dependence: Involvement of calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P, and arachidonic acid-derived metabolites. Peptides, 2005, 26(8), 1346-1355.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.031] [PMID: 16042975] ].

The substance P (SP) plays an important role in spinal nociceptive processing and as a regulatory effector of opioid-dependent analgesic processes [24Foran, SE; Carr, DB; Lipkowski, AW; Maszczynska, I; Marchand, JE; Misicka, A; Beinborn, M; Kopin, AS; Kream, RM Inhibition of morphine tolerance development by a substance P-opioid peptide chimera. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 2000, 295 (3)(3), 1142-8. Dec], with increased spinal activity of SP together with CGRP contributing to the development of opioid tolerance-dependence [25Powell, K.J.; Ma, W.; Sutak, M.; Doods, H.; Quirion, R.; Jhamandas, K. Blockade and reversal of spinal morphine tolerance by peptide and non-peptide calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonists. Br. J. Pharmacol., 2000, 131(5), 875-884.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0703655] [PMID: 11053206] ].

Prostaglandins (PGs) (such as prostaglandin E2) are lipid products generated from arachidonic acid by the action of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2). The synthesis and release of prostaglandins from astrocytes [26Marriott, D.; Wilkin, G.P.; Coote, P.R.; Wood, J.N. Eicosanoid synthesis by spinal cord astrocytes is evoked by substance P; possible implications for nociception and pain. Adv. Prostaglandin Thromboxane Leukot. Res., 1991, 21B, 739-741.

[PMID: 1705083] , 27Marriott, D.R.; Wilkin, G.P.; Wood, J.N. Substance P-induced release of prostaglandins from astrocytes: regional specialisation and correlation with phosphoinositol metabolism. J. Neurochem., 1991, 56(1), 259-265.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02590.x] [PMID: 1702831] ] and neurons [28Hua, X.Y.; Chen, P.; Marsala, M.; Yaksh, T.L. Intrathecal substance P-induced thermal hyperalgesia and spinal release of prostaglandin E2 and amino acids. Neuroscience, 1999, 89(2), 525-534.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00488-6] [PMID: 10077333] ] in the spinal cord can be induced by the activation of NMDA receptors [29Dirig, D.M.; Yaksh, T.L. In vitro prostanoid release from spinal cord following peripheral inflammation: effects of substance P, NMDA and capsaicin. Br. J. Pharmacol., 1999, 126(6), 1333-1340.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0702427] [PMID: 10217526] , 30Malmberg, A.B.; Yaksh, T.L. Antinociceptive actions of spinal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents on the formalin test in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 1992, 263(1), 136-146.

[PMID: 1403779] ] and NK-1 receptors. Moreover, these prostaglandins act retrogradely (positive feedback) on primary afferent terminals to stimulate further the release of excitatory amino acids (l-glutamate) and neuropeptides (SP) [31Southall, M.D.; Michael, R.L.; Vasko, M.R. Intrathecal NSAIDS attenuate inflammation-induced neuropeptide release from rat spinal cord slices. Pain, 1998, 78(1), 39-48.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00113-4] [PMID: 9822210] -33Vasko, M.R.; Campbell, W.B.; Waite, K.J. Prostaglandin E2 enhances bradykinin-stimulated release of neuropeptides from rat sensory neurons in culture. J. Neurosci., 1994, 14(8), 4987-4997.

[PMID: 7519258] ]. Experimental studies have shown that the increase of the positive feedback between neuropeptides and prostaglandins in the dorsal horn, under the influence of chronic morphine, may be connected to the induction of the opioid tolerant-dependent state [20Trang, T.; Quirion, R.; Jhamandas, K. The spinal basis of opioid tolerance and physical dependence: Involvement of calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P, and arachidonic acid-derived metabolites. Peptides, 2005, 26(8), 1346-1355.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.031] [PMID: 16042975] ].

The spinal lipoxygenase (LOX) metabolites from arachidonic acid, such as leukotriene B4 (LTB4), play a role in the induction of hyperalgesia and development of opioid analgesic tolerance. Also, chronic morphine exposure probably increases activity in the LOX cascade at the spinal level [34Trang, T.; McNaull, B.; Quirion, R.; Jhamandas, K. Involvement of spinal lipoxygenase metabolites in hyperalgesia and opioid tolerance. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 2004, 491(1), 21-30.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.022] [PMID: 15102529] ].

Morphine toxicity occurs by the accumulation of its metabolites without analgesic potency but has an important neurotoxic effect [21Smith, H.S. Opioid metabolism. Mayo Clin. Proc., 2009, 84(7), 613-624.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60750-7] [PMID: 19567715] ]. In man, morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G) and morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G) are the major metabolites of morphine [35Christrup, L.L. Morphine metabolites. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand., 1997, 41(1 Pt 2), 116-122.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04625.x] [PMID: 9061094] ]. Although M6G contributes to the analgesic effect of morphine, the M3G metabolite produces neurotoxicity [21Smith, H.S. Opioid metabolism. Mayo Clin. Proc., 2009, 84(7), 613-624.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60750-7] [PMID: 19567715] , 36Smith, M.T. Neuroexcitatory effects of morphine and hydromorphone: evidence implicating the 3-glucuronide metabolites. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol., 2000, 27(7), 524-528.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03290.x] [PMID: 10874511] ]. However, toxicity can also be produced by the neurotoxic action toxicity of the high-dose opioid itself.

The adverse effects of morphine can be divided into dose-dependent and dose-independent effects, with the most common dose-dependent ones being nausea, vomiting, and drowsiness, which always appear after a certain dose and disappear within a few days or on decreasing the dosage. The most frequent dose-independent adverse effects include constipation, and hallucinations, and these appear regardless of the dose administered and do not disappear as there is no phenomenon of tolerance. Respiratory depression is certainly the most serious adverse effect. However, this side effect is very rare, and can be treated with naloxone and minimized by careful titration [37Baldini, A.; Von Korff, M.; Lin, E.H. A Review of Potential Adverse Effects of Long-Term Opioid Therapy: A Practitioners Guide. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord., 2012, 14(3), 1013.

[PMID: 23106029] ]. Common side effects include nausea and vomiting, which occur in one to two thirds of patients taking opioids [38Opioid analgesic therapy. In: Doyle, D.; Hanks, G.W.; MacDonald, N., Eds.; Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, 2nd ed; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 1998; pp. 331-335.]. These are particularly common complications at the start of treatment with opioids, but usually disappear during the first week of treatment.

Although the above side effects are still not entirely understood, multiple and complex mechanisms are likely to be involved in both the peripheral and central nervous system, including (I) stimulation of the vestibular apparatus (with symptoms often including vertigo and worsening with motion), (II) direct effects on the chemoreceptor trigger zone, and (III) delayed gastric emptying (with symptoms of early satiety and bloating, and also worsening postprandially) [39Smith, H.S.; Laufer, A. Opioid induced nausea and vomiting. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 2014, 722(5), 67-78.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.09.074] [PMID: 24157979] ]. Antiemetic drugs used to suppress emesis or the vomiting associated with the clinical use of morphine include the following: haloperidol (Dopamine 2 receptor antagonist), promethazine (Histamine 1 receptor antagonist), naloxone (mu/delta opioid receptors antagonist), ondansetron (5-HT3 receptor antagonist), scopolamine (Muscarinic1 receptor antagonist), aprepitant (Tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist) and dronabinol (cannabinoid CB1 agonist) [39Smith, H.S.; Laufer, A. Opioid induced nausea and vomiting. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 2014, 722(5), 67-78.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.09.074] [PMID: 24157979] ].

The sedative effects of opioids are well known in patients not previously treated with opioids [40Byas-Smith, M.G.; Chapman, S.L.; Reed, B.; Cotsonis, G. The effect of opioids on driving and psychomotor performance in patients with chronic pain. Clin. J. Pain, 2005, 21(4), 345-352.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.ajp.0000125244.29279.c1] [PMID: 15951653] ].

Sedation and cognitive impairment occur early in treatment, with tolerance to these effects taking place when a stable dose is reached [41Jovey, R.D.; Ennis, J.; Gardner-Nix, J.; Goldman, B.; Hays, H.; Lynch, M.; Moulin, D. Use of opioid analgesics for the treatment of chronic noncancer paina consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society, 2002. Pain Res. Manag., 2003, 8(Suppl. A), 3A-28A.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2003/436716] [PMID: 14685304] ]. Morphine causes sedation and somnolence, possibly due to the anticholinergic activity of opioids, with drowsiness also being common at the beginning of treatment and consequently being a risk for patients who drive [42Coupe, M.H.; Stannard, C. Opioids in persistent non-cancer pain. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia. Critical Care and Pain, 2007, 7(3), 100-103.]. These adverse effects can be alleviated by reducing the dose through opioid rotation, and also by the use of psychostimulants such as methylphenidate [43Bruera, E.; Miller, M.J.; Macmillan, K.; Kuehn, N. Neuropsychological effects of methylphenidate in patients receiving a continuous infusion of narcotics for cancer pain. Pain, 1992, 48(2), 163-166.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(92)90053-E] [PMID: 1589233] -46Reissig, J.E.; Rybarczyk, A.M. Pharmacologic treatment of opioid-induced sedation in chronic pain. Ann. Pharmacother., 2005, 39(4), 727-731.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1345/aph.1E309] [PMID: 15755795] ] to improve subjective drowsiness and psychomotor performance scores [47Ahmedzai, S. New approaches to pain control in patients with cancer. Eur. J. Cancer, 1997, 33(Suppl. 6), S8-S14.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00205-0] [PMID: 9404234] ]. Constipation occurs in 40-95% of opioid-treated patients, and can even happen after a single dose of morphine [48Swegle, J.M.; Logemann, C. Management of common opioid-induced adverse effects. Am. Fam. Physician, 2006, 74(8), 1347-1354.

[PMID: 17087429] ]. As this can decrease the quality of life and work productivity of patients, in cases of severe constipation patients should reduce the opioid dose, resulting in decreased analgesia. However, constipation is unlikely to improve over time, and therefore it should be monitored during treatment with morphine [49Schug, S.A.; Garrett, W.R.; Gillespie, G. Opioid and non-opioid analgesics. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol., 2003, 17(1), 91-110.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/bean.2003.0267] [PMID: 12751551] ]. This persistent effect often requires a simultaneous additional treatment [41Jovey, R.D.; Ennis, J.; Gardner-Nix, J.; Goldman, B.; Hays, H.; Lynch, M.; Moulin, D. Use of opioid analgesics for the treatment of chronic noncancer paina consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society, 2002. Pain Res. Manag., 2003, 8(Suppl. A), 3A-28A.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2003/436716] [PMID: 14685304] , 42Coupe, M.H.; Stannard, C. Opioids in persistent non-cancer pain. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia. Critical Care and Pain, 2007, 7(3), 100-103.], with several studies having suggested that mu-opioid receptors play a key role in opioid-induced constipation [50Mori, T.; Shibasaki, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Shibasaki, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Wang, E.; Masukawa, D.; Yoshizawa, K.; Horie, S.; Suzuki, T. Mechanisms that underlie μ-opioid receptor agonist-induced constipation: differential involvement of μ-opioid receptor sites and responsible regions. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 2013, 347(1), 91-99.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/jpet.113.204313] [PMID: 23902939] ]. Related to this, in the treatment of opioid-induced constipation, recent positive clinical efficacy data have been obtained with two peripherally acting antagonists, methylnaltrexone and alvimopan, of the mu-opioid receptor [51Camilleri, M. Opioid-induced constipation: challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 2011, 106(5), 835-842.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2011.30] [PMID: 21343919] ]. Finally, pruritus or severe itching of the skin occurs frequently with opioid use and is difficult to treat. Although antihistamines have been found to be useful for counteracting this itching, this adverse effect of opioids can often lead to treatment discontinuation [52Recommendations for the appropriate use of opioids for persistent non-cancer pain. A consensus statement prepared on behalf of the Pain Society, the Royal College of Anaesthetists, the Royal College of General Practitioners and the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Ed. The Pain Society. March 2004. Available from:

http://www.anaesthesiauk.com/documents/opioids_doc_2004.pdf, 2004.].

4. STRATEGIES TO MANAGE THE ADVERSE EFFECTS OF MORPHINE

Effective pain management with opioids, such as morphine remains a major clinical challenge and can fail due to: (1) inadequate analgesia, (2) excessive adverse effects, or (3) a combination of both these factors [53Coupe, M.H.; Stannard, C. Opioids in persistent non-cancer pain. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia. Critical Care and Pain, 2007, 7(3), 100-103., 54Cherny, N.J.; Chang, V.; Frager, G.; Ingham, J.M.; Tiseo, P.J.; Popp, B.; Portenoy, R.K.; Foley, K.M.; Foley, K.M. Opioid pharmacotherapy in the management of cancer pain: a survey of strategies used by pain physicians for the selection of analgesic drugs and routes of administration. Cancer, 1995, 76(7), 1283-1293.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19951001)76:7<1283::AID-CNCR2820760728>3.0.CO;2-0] [PMID: 8630910] ], with multiple approaches having been attempted to address this problem using different pharmacological options.

For several years, researchers have been developing new pharmaceutical strategies to improve the effectiveness of analgesics and to prevent or at least reduce the severity of adverse effects by combining an analgesic with a second agent, which may or may not be an analgesic [3Smith, H.S. Combination opioid analgesics. Pain Physician, 2008, 11(2), 201-214.

[PMID: 18354712] ]. Related to this, a second “non-opioid agent” may be referred to as a “coanalgesic” or “adjuvant analgesic”. This incorporation of adjuncts in opioid therapy can help to reduce pain and improve the quality of life in sufferers.

Adjuncts to opioid therapy include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., ibuprofen) [55Plummer, J.L.; Owen, H.; Ilsley, A.H.; Tordoff, K. Sustained-release ibuprofen as an adjunct to morphine patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth. Analg., 1996, 83(1), 92-96.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199607000-00016] [PMID: 8659772] ], acetaminophen [56Schug, S.A.; Sidebotham, D.A.; McGuinnety, M.; Thomas, J.; Fox, L. Acetaminophen as an adjunct to morphine by patient-controlled analgesia in the management of acute postoperative pain. Anesth. Analg., 1998, 87(2), 368-372.

[PMID: 9706932] ], antiarrhythmics, anticonvulsants [57Tesfaye, S.; Selvarajah, D. Morphine, gabapentin, or their combination for neuropathic pain. N. Engl. J. Med., 2005, 352(25), 2650-2651.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200506233522520] [PMID: 15981312] ], antidepressants (such as desipramine) [58Ossipov, M.H.; Malseed, R.T.; Goldstein, F.J. Augmentation of central and peripheral morphine analgesia by desipramine. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther., 1982, 259(2), 222-229.

[PMID: 7181579] ], antipsychotics, baclofen, benzodiazepines, capsaicin, calcium channel blockers, clonidine hydrochloride [59De Kock, M.F.; Pichon, G.; Scholtes, J.L. Intraoperative clonidine enhances postoperative morphine patient-controlled analgesia. Can. J. Anaesth., 1992, 39(6), 537-544.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03008314] [PMID: 1643675] ], central nervous system stimulants, corticosteroids, local anesthetics, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists and scopolamine [60Goldstein, F.J. Adjuncts to opioid therapy. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc., 2002, 102(9)(Suppl. 3), S15-S21.

[PMID: 12356036] , 61Laguerre, P.J. Alternatives and adjuncts to opioids for the treatment of chronic pain. N. C. Med. J., 2013, 74(3), 209-214.

[PMID: 23940888] ]. Of these, some (e.g., acetaminophen) are currently routinely used, whereas others (e.g., nifedipine [calcium channel blocker]) are only administered on a limited basis. However, one problem with the use of many adjuvant analgesics is that they have the potential to cause side effects which may be additive to the opioid adverse effects, thus further complicating treatment [4Portenoy, R.K. Adjuvant analgesic agents. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am., 1996, 10(1), 103-119.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70329-4] [PMID: 8821562] ].

Omega-3 Fatty Acids Combined With Morphine

Pain in physiological and pathological conditions can be treated with medication, as well as by nutritional strategies or using dietary supplements [62Sulindro-Ma, M. Audette , JF; Bailey, A. Nutrition and supplements for pain management, Integrative pain medicine; Humana Press: USA, 2008, pp. 417-445.]. It is well known that certain food components (administered in foods or in their pure forms) have been shown to play a role as medicaments. Thus, dietary modulation of an inflammatory reaction may be a therapeutic option for treating a variety of diseases [63Visioli, F.; Poli, A.; Richard, D.; Paoletti, R. Modulation of inflammation by nutritional interventions. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep., 2008, 10(6), 451-453.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11883-008-0069-0] [PMID: 18937889] ]. In fact, the omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (omega-3 PUFAs) in the form of fish oil are probably the best known examples of how diet can reduce inflammation [64Minton, K. Inflammasome: fishing for anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Immunol., 2013, 13(8), 545.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nri3498] [PMID: 23846115] ].

The human body can synthesize numerous fatty acids referred to as non essential, while other fatty acids called essential fatty acids (EFAs) should be incorporated into the diet because they cannot be synthesized by humans [65Simopoulos, A.P. Evolutionary aspects of diet and essential fatty acids. In: Fatty Acids and Lipids-New Findings; Hamazaki, T.; Okuyama, H., Eds.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2001; Vol. 88, pp. 18-27.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000059742] ]. These include Linoleic acid (LA), an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid (omega-6 PUFA) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), an omega-3 PUFA.

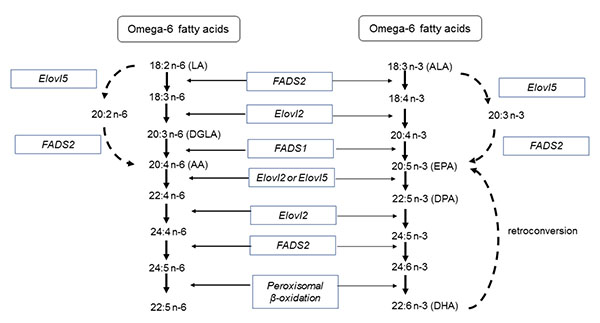

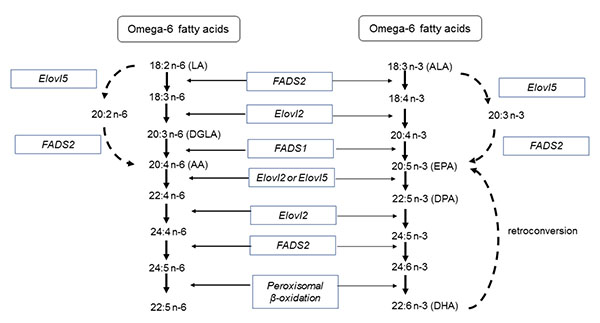

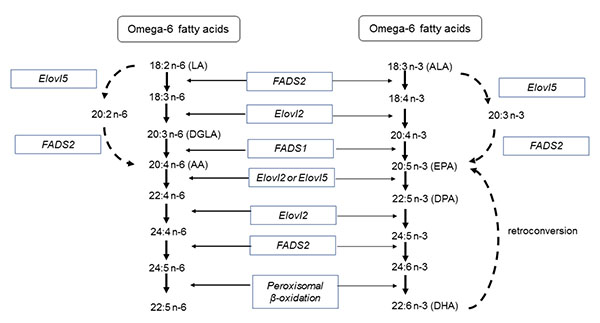

The parent 18-carbon fatty acid, alpha--linolenic acid (ALA; 18:3n−3) is present in various vegetable oils, such as flaxseed, linseed, canola and soy oils, and ALA can be metabolized to other more unsaturated long-chain members of the omega-3 PUFAs by the insertion of additional double bonds during consecutive elongation and desaturation. In this way, it can be metabolically converted to various omega-3 PUFAs, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5n−3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6n−3). This metabolic conversion of ALA occurs primarily in the endoplasmic reticulum in the liver, and involves a series of elongation enzymes that sequentially add 2-carbon units to the fatty acid backbone and desaturation enzymes that insert double bonds into the molecules [66Arterburn, L.M.; Hall, E.B.; Oken, H. Distribution, interconversion, and dose response of n-3 fatty acids in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2006, 83(6)(Suppl.), 1467S-1476S.

[PMID: 16841856] ].

The final conversion of ALA to DHA requires a translocation to the peroxisome for a β-oxidation reaction, with the capacity to generate DHA from ALA being higher in women than men [67Vermunt, S.H.; Mensink, R.P.; Simonis, M.M.; Hornstra, G. Effects of dietary alpha-linolenic acid on the conversion and oxidation of 13C-alpha-linolenic acid. Lipids, 2000, 35(2), 137-142.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02664762] [PMID: 10757543] ]. Moreover, several studies have shown that ≥15–35% of dietary ALA is rapidly catabolized to carbon dioxide for energy [67Vermunt, S.H.; Mensink, R.P.; Simonis, M.M.; Hornstra, G. Effects of dietary alpha-linolenic acid on the conversion and oxidation of 13C-alpha-linolenic acid. Lipids, 2000, 35(2), 137-142.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02664762] [PMID: 10757543] -71Gerster, H. Can adults adequately convert alpha-linolenic acid (18:3n-3) to eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n-3)? Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res., 1998, 68(3), 159-173.

[PMID: 9637947] ]. In healthy young men, approximately 8% of dietary ALA is converted to EPA and 0-4% is converted to DHA [72Burdge, G. Alpha-linolenic acid metabolism in men and women: nutritional and biological implications. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care, 2004, 7(2), 137-144.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00075197-200403000-00006] [PMID: 15075703] ], whereas in healthy young women, approximately 21% of dietary ALA is converted to EPA and 9% is converted to DHA [68Burdge, G.C.; Wootton, S.A. Conversion of alpha-linolenic acid to eicosapentaenoic, docosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids in young women. Br. J. Nutr., 2002, 88(4), 411-420.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/BJN2002689] [PMID: 12323090] ]. Finally, DHA can be retroconverted to EPA at a low basal rate and following supplementation [72Burdge, G. Alpha-linolenic acid metabolism in men and women: nutritional and biological implications. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care, 2004, 7(2), 137-144.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00075197-200403000-00006] [PMID: 15075703] -75Das, U.N. Biological significance of essential fatty acids. J. Assoc. Physicians India, 2006, 54, 309-319.

[PMID: 16944615] ] (Fig. 1 ).

).

The two most important omega-3 PUFAs involved with human physiology and pharmacology effects are DHA and EPA, but due to the low conversion efficiency from ALA it is recommended that EPA and DHA are obtained from additional sources, such as fish oil supplements.

Linoleic acid (LA, C18:2n-6) can be metabolized to other more unsaturated long-chain members of the n-6 family by the insertion of additional double bonds during consecutive elongation and desaturation mechanisms. In this way, LA is converted to Arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6) via γ-linolenic acid (GLA, 18:3n-6) and dihomo-γ-linolenic acid (DGLA, 20:3n-6) (Fig. 1 ).

).

As the same enzymes involved in omega-3 PUFA synthesis are responsible for the conversion of omega-6 PUFA LA to AA, background diet can influence the conversion of these fatty acids. Nevertheless, the regulation of desaturation and the elongation of omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs are still poorly understood, although they are known to involve competitive substrates, enzyme regulation, and nutritional, hormonal, physiological and pathological factors [76Simopoulos, A.P. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed. Pharmacother., 2002, 56(8), 365-379.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0753-3322(02)00253-6] [PMID: 12442909] ].

Since ALA and LA are metabolized by the same set of enzymes, a natural competition exists between these two fatty acids, whereby delta-5-desaturase and delta-6-desaturase will exhibit an affinity to metabolize omega-3 PUFAs over omega-6 PUFAs, provided that they exist at a ratio of 1: 1–4. However, the higher consumption of LA in the typical western diet causes an increase in the preference of these enzymes to metabolize omega-6 PUFAs, leading to AA synthesis, despite the fact that these enzymes show a higher affinity for n-3 PUFAs [77Simopoulos, A.P. Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune diseases. J. Am. Coll. Nutr., 2002, 21(6), 495-505.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2002.10719248] [PMID: 12480795] ] for ratios of 15:1 to 16.7:1 [78Kang, J.X. The importance of omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cell function. The gene transfer of omega-3 fatty acid desaturase. In: Omega-6/Omega-3 Essential Fatty Acid Ratio: The Scientific Evidence; Simopoulos, A.P.; Cleland, L.G., Eds.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2003; Vol. 92, pp. 23-36.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000073790] ].

Excessive amounts of omega-6 PUFAs promote the pathogenesis of many diseases, including cardiovascular disease, chronic inflammatory diseases such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer's disease, cancer and autoimmune diseases [79Calder, P.C. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: nutrition or pharmacology? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol., 2013, 75(3), 645-662.

[PMID: 22765297] , 80Patterson, E; Wall, R; Fitzgerald, GF; Ross, RP; Stanton, C Health Implications of High Dietary Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. J. Nutr. Metab., 2012, 75(3), 539-426.]. However, supplementation of the diet with fish oil (EPA and DHA) has been shown to correct this imbalance by partially replacing AA in the cell membranes of platelets, erythrocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, and hepatocytes, where AA is usually found at high proportions [79Calder, P.C. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: nutrition or pharmacology? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol., 2013, 75(3), 645-662.

[PMID: 22765297] , 80Patterson, E; Wall, R; Fitzgerald, GF; Ross, RP; Stanton, C Health Implications of High Dietary Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. J. Nutr. Metab., 2012, 75(3), 539-426.].

Omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs have opposite effects, and the balance between them is critical as diet plays an important role in determining the body’s inflammation status. Whereas omega-6 PUFAs derived signaling molecules are inflammatory, the omega-3 PUFA derived signaling molecules are anti-inflammatory [81Goldberg, R.J.; Katz, J. A meta-analysis of the analgesic effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for inflammatory joint pain. Pain, 2007, 129(1-2), 210-223.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.020] [PMID: 17335973] ], with EPA and DHA, for example, being precursors of potent anti-inflammatory lipid mediators such as resolvins and protectins [82Pérez, J.; Ware, M.A.; Chevalier, S.; Gougeon, R.; Shir, Y. Dietary omega-3 fatty acids may be associated with increased neuropathic pain in nerve-injured rats. Anesth. Analg., 2005, 101(2), 444-448.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000158469.11775.52] [PMID: 16037160] ].

In both preclinical and clinical studies, omega-3 PUFAs have been shown to contribute to the reduction of inflammatory pain in different situations, such as inflammatory bowel disease [83Stenson, W.F.; Cort, D.; Rodgers, J.; Burakoff, R.; DeSchryver-Kecskemeti, K.; Gramlich, T.L.; Beeken, W. Dietary supplementation with fish oil in ulcerative colitis. Ann. Intern. Med., 1992, 116(8), 609-614.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-116-8-609] [PMID: 1312317] ], chronic headaches [84Ramsden, C.E.; Faurot, K.R.; Zamora, D.; Palsson, O.S.; Maclntosh, B.A.; Gaylord, S.; Taha, A.Y.; Rapport, S.I.; Hibbeln, J.R.; Davis, J.M.; Mann, J.D. Targeted alteration of dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids for the treatment of chronic headaches: a randomized trial. Pain, 2015, 156(4), 587-596.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460348.84965.47] [PMID: 25790451] ], knee osteoarthritis [85Hill, C.L.; March, L.M.; Aitken, D.; Lester, S.E.; Battersby, R.; Hynes, K.; Fedorova, T.; Proudman, S.M.; James, M.; Cleland, L.G.; Jones, G. Fish oil in knee osteoarthritis: a randomised clinical trial of low dose versus high dose. Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2016, 75(1), 23-29.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207169] [PMID: 26353789] , 86Torres-Guzman, A.M.; Morado-Urbina, C.E.; Alvarado-Vazquez, P.A.; Acosta-Gonzalez, R.I.; Chávez-Piña, A.E.; Montiel-Ruiz, R.M.; Jimenez-Andrade, J.M. Chronic oral or intraarticular administration of docosahexaenoic acid reduces nociception and knee edema and improves functional outcomes in a mouse model of Complete Freunds Adjuvant-induced knee arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther., 2014, 16(2), R64.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/ar4502] [PMID: 24612981] ], inflammatory joint pain [81Goldberg, R.J.; Katz, J. A meta-analysis of the analgesic effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for inflammatory joint pain. Pain, 2007, 129(1-2), 210-223.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.020] [PMID: 17335973] ], neck or back pain (discogenic pain) [87Maroon, J.C.; Bost, J.W. Omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil) as an anti-inflammatory: an alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for discogenic pain. Surg. Neurol., 2006, 65(4), 326-331.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surneu.2005.10.023] [PMID: 16531187] ], rheumatoid arthritis [88Berbert, A.A.; Kondo, C.R.; Almendra, C.L.; Matsuo, T.; Dichi, I. Supplementation of fish oil and olive oil in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition, 2005, 21(2), 131-136.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2004.03.023] [PMID: 15723739] -96Nielsen, G.L.; Faarvang, K.L.; Thomsen, B.S.; Teglbjaerg, K.L.; Jensen, L.T.; Hansen, T.M.; Lervang, H.H.; Schmidt, E.B.; Dyerberg, J.; Ernst, E. The effects of dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, double blind trial. Eur. J. Clin. Invest., 1992, 22(10), 687-691.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.1992.tb01431.x] [PMID: 1459173] ] neuropathic pain [82Pérez, J.; Ware, M.A.; Chevalier, S.; Gougeon, R.; Shir, Y. Dietary omega-3 fatty acids may be associated with increased neuropathic pain in nerve-injured rats. Anesth. Analg., 2005, 101(2), 444-448.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000158469.11775.52] [PMID: 16037160] , 97Ko, G.D.; Nowacki, N.B.; Arseneau, L.; Eitel, M.; Hum, A. Omega-3 fatty acids for neuropathic pain: case series. Clin. J. Pain, 2010, 26(2), 168-172.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181bb8533] [PMID: 20090445] ], musculoskeletal injury [98Eriksen, W.; Sandvik, L.; Bruusgaard, D. Does dietary supplementation of cod liver oil mitigate musculoskeletal pain? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr., 1996, 50(10), 689-693.

[PMID: 8909937] ] and dysmenorrhea [99Harel, Z.; Biro, F.M.; Kottenhahn, R.K.; Rosenthal, S.L. Supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the management of dysmenorrhea in adolescents. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 1996, 174(4), 1335-1338.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70681-6] [PMID: 8623866] ]. In these clinical studies, different effective doses of fish oils (DHA and EPA) and treatment times were utilized Table (1), with other preclinical studies also having revealed the antinociceptive effect of different types of omega-3 PUFAs [100Yehuda, S.; Leprohon-Greenwood, C.E.; Dixon, L.M.; Coscina, D.V. Effects of dietary fat on pain threshold, thermoregulation and motor activity in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav., 1986, 24(6), 1775-1777.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0091-3057(86)90519-8] [PMID: 3737642] -102Veigas, J.M.; Williams, P.J.; Halade, G.; Rahman, M.M.; Yoneda, T.; Fernandes, G. Fish oil concentrate delays sensitivity to thermal nociception in mice. Pharmacol. Res., 2011, 63(5), 377-382.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2011.02.004] [PMID: 21345372] ].

Recent pre-clinical studies in our laboratory have demonstrated that acute treatment with morphine following 16 days of omega-3 PUFAs (DHA and EPA) had a greater antinociceptive effect than morphine alone at the same dose, thus revealing an additive effect. However, omega-3 PUFA chronic treatment with morphine attenuated or blocked the development of tolerance to morphine after 16 or 30 days of treatment, respectively [76Simopoulos, A.P. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed. Pharmacother., 2002, 56(8), 365-379.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0753-3322(02)00253-6] [PMID: 12442909] ].

Morphine is known to produce a decrease in body weight in rats [103Tejwani, G.A.; Rattan, A.K.; Sribanditmongkol, P.; Sheu, M.J.; Zuniga, J.; McDonald, J.S. Inhibition of morphine-induced tolerance and dependence by a benzodiazepine receptor agonist midazolam in the rat. Anesth. Analg., 1993, 76(5), 1052-1060.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199305000-00025] [PMID: 8484507] ], but omega-3 PUFA chronic treatment with morphine can reduce this effect. Moreover, morphine reduces the gastrointestinal transit, whereas co-administration of omega-3 PUFAs with morphine blocks this morphine effect [104Escudero, G.E.; Romañuk, C.B.; Toledo, M.E.; Olivera, M.E.; Manzo, R.H.; Laino, C.H. Analgesia enhancement and prevention of tolerance to morphine: beneficial effects of combined therapy with omega-3 fatty acids. J. Pharm. Pharmacol., 2015, 67(9), 1251-1262.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jphp.12416] [PMID: 26011306] ].

We recently demonstrated that naloxone, a pure opioid antagonist, blocks the analgesia produced by omega-3 PUFAs alone or in co-administration of omega-3 PUFAs with morphine, suggesting that the analgesic activity of both might be exerted via a mechanism related to the opioid system [104Escudero, G.E.; Romañuk, C.B.; Toledo, M.E.; Olivera, M.E.; Manzo, R.H.; Laino, C.H. Analgesia enhancement and prevention of tolerance to morphine: beneficial effects of combined therapy with omega-3 fatty acids. J. Pharm. Pharmacol., 2015, 67(9), 1251-1262.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jphp.12416] [PMID: 26011306] ].

Furthermore, a new pharmaceutical mixture (omega-3 PUFA/morphine) obtained by dissolving morphine in salmon oil allowed the concomitant oral administration of both components, which showed analgesic activity with a subtherapeutic dose of morphine, lower side-effects associated with morphine treatment, and also prevented or least reduced the possibility of developing tolerance to the analgesic effect of morphine [104Escudero, G.E.; Romañuk, C.B.; Toledo, M.E.; Olivera, M.E.; Manzo, R.H.; Laino, C.H. Analgesia enhancement and prevention of tolerance to morphine: beneficial effects of combined therapy with omega-3 fatty acids. J. Pharm. Pharmacol., 2015, 67(9), 1251-1262.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jphp.12416] [PMID: 26011306] , 105Laino, C; Manzo, RH; Olivera, ME; Romañuk, CB inventors; Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Universidad Nacional de la Rioja and CONICET, assignee. March 15th, 2012 Composición farmacéutica para el tratamiento del dolor, procedimiento de obtención y métodos de tratamiento. Argentina Patent Application pending P-20120100854, 2012. March 15th].

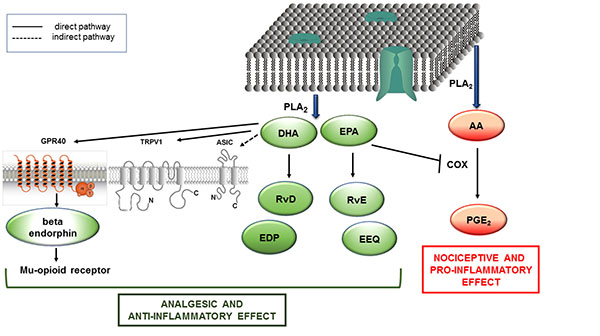

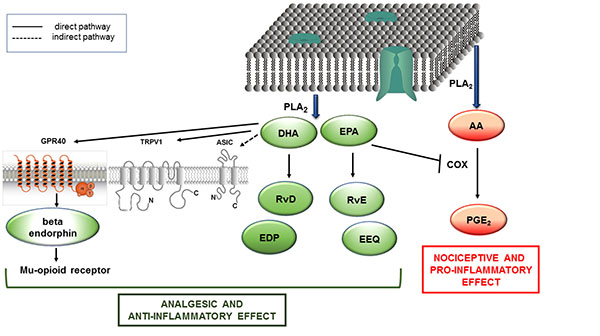

The exact mechanism by which omega-3 PUFAs reduce pain is not fully understood, but some reports about the mechanisms underlying the antinociceptive effect of omega-3 PUFAs have suggested that this pain reduction occurs through:

-

Inhibition of the production of proinflammatory eicosanoids and cytokines via the suppression of the arachidonic acid cascade [106Zaloga, G.P.; Marik, P. Lipid modulation and systemic inflammation. Crit. Care Clin., 2001, 17(1), 201-217.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-0704(05)70160-3] [PMID: 11219230] -109Gaudette, D.C.; Holub, B.J. Albumin-bound docosahexaenoic acid and collagen-induced human platelet reactivity. Lipids, 1990, 25(3), 166-169.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02544332] [PMID: 2139712] ]. -

Analgesic action of the omega-3 PUFA -derived mediators, with recent studies having demonstrated that EPA and DHA act/serve as precursors for the E-series (RvE1, RvE2) and D-series (RvD1, RvD2) resolvins, respectively, which are potent analgesics [110Serhan, C.N. Novel eicosanoid and docosanoid mediators: resolvins, docosatrienes, and neuroprotectins. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care, 2005, 8(2), 115-121.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00075197-200503000-00003] [PMID: 15716788] -114Huang, L.; Wang, C.F.; Serhan, C.N.; Strichartz, G. Enduring prevention and transient reduction of postoperative pain by intrathecal resolvin D1. Pain, 2011, 152(3), 557-565.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.021] [PMID: 21255928] ]. -

Regulatory action on both the peripheral and central transient receptor potential of vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) and acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) for omega-3 PUFAs [102Veigas, J.M.; Williams, P.J.; Halade, G.; Rahman, M.M.; Yoneda, T.; Fernandes, G. Fish oil concentrate delays sensitivity to thermal nociception in mice. Pharmacol. Res., 2011, 63(5), 377-382.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2011.02.004] [PMID: 21345372] , 115Matta, J.A.; Miyares, R.L.; Ahern, G.P. TRPV1 is a novel target for omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Physiol., 2007, 578(Pt 2), 397-411.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2006.121988] [PMID: 17038422] ].

The modulation of the TRPV1 receptor function produces pain relief at the level of the primary sensory neuron. While TRPV1 receptor activation by prolonged application of an agonist results in the release of central transmitters (glutamate and substance P) from nociceptive afferents and consequently a desensitization to generate action potentials, a TRPV1 receptor antagonist blocks the ion channel pore [116Trevisani, M.; Szallas, A. Targeting TRPV1: Challenges and Issues in Pain Management. Open Drug Discov. J., 2010, 2, 37-49.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1877381801002030037] ]. Interestingly, whereas DHA is a potent TRPV1 agonist, EPA inhibits the activation of this cation channel by various agonists [115Matta, J.A.; Miyares, R.L.; Ahern, G.P. TRPV1 is a novel target for omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Physiol., 2007, 578(Pt 2), 397-411.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2006.121988] [PMID: 17038422] ].

The acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs), such as ASIC1a, ASIC1b and ASIC3, have been implicated in pain perception. ASICs are excitatory cation channels directly gated by extracellular protons of many painful conditions [117Julius, D.; Basbaum, A.I. Molecular mechanisms of nociception. Nature, 2001, 413(6852), 203-210.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/35093019] [PMID: 11557989] , 118Cadiou, H.; Studer, M.; Jones, N.G.; Smith, E.S.; Ballard, A.; McMahon, S.B.; McNaughton, P.A. Modulation of acid-sensing ion channel activity by nitric oxide. J. Neurosci., 2007, 27(48), 13251-13260.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2135-07.2007] [PMID: 18045919] ]. However, recent studies have demonstrated that omega-3 PUFAs decrease the mRNA expression of ASIC1a, ASIC3 and TRPV1, suggesting a reduced inflammatory status, which may be the reason for the increased pain threshold [102Veigas, J.M.; Williams, P.J.; Halade, G.; Rahman, M.M.; Yoneda, T.; Fernandes, G. Fish oil concentrate delays sensitivity to thermal nociception in mice. Pharmacol. Res., 2011, 63(5), 377-382.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2011.02.004] [PMID: 21345372] ].

-

Increasing the release of β-endorphin. Nakamoto et al. [119Nakamoto, K.; Nishinaka, T.; Ambo, A.; Mankura, M.; Kasuya, F.; Tokuyama, S. Possible involvement of β-endorphin in docosahexaenoic acid-induced antinociception. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 2011, 666(1-3), 100-104.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.05.047] [PMID: 21658380] ] demonstrated that the DHA facilitated the release of β-endorphin, mediated (at least in part) through GPR40 signaling, and finally the stimulation of μ- and δ-opioid receptors induced antinociception [120Nakamoto, K.; Nishinaka, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Kasuya, F.; Mankura, M.; Koyama, Y.; Tokuyama, S. Involvement of the long-chain fatty acid receptor GPR40 as a novel pain regulatory system. Brain Res., 2012, 1432, 74-83.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.012] [PMID: 22137657] ]. -

Analgesic action of the epoxidized metabolites derived from omega-3 PUFAs DHA (epoxydocosapentaenoic acid, EDP) and EPA (epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid, EEQ), which are metabolized by cytochrome P450. The metabolites produce epoxy docosapentaenoic acid and epoxy eicosatetraenoic acid, and have a direct antinociceptive role [121Wagner, K.; Vito, S.; Inceoglu, B.; Hammock, B.D. The role of long chain fatty acids and their epoxide metabolites in nociceptive signaling. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat., 2014, 113-115, 2-12.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2014.09.001] [PMID: 25240260] , 122Morisseau, C.; Inceoglu, B.; Schmelzer, K.; Tsai, H.J.; Jinks, S.L.; Hegedus, C.M.; Hammock, B.D. Naturally occurring monoepoxides of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are bioactive antihyperalgesic lipids. J. Lipid Res., 2010, 51(12), 3481-3490.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M006007] [PMID: 20664072] ] (Fig. 2 ).

).

LIST OF ABREVIATIONS

| AA | = Arachidonic acid |

| ALA | = Alpha-linolenic acid |

| ASICs | = Acid-Sensing Ion Channels |

| ASIC1a | = Acid-Sensing Ion Channels (ASICs) subtype 1a |

| ASIC1b | = Acid-Sensing Ion Channels subtype 1b |

| ASIC3 | = Acid-Sensing Ion Channels type 3 |

| CB | = Cannabinoid |

| CGRP | = Calcitonin gene-related peptide |

| DGLA | = Dihomo-γ-linolenic acid |

| DHA | = Docosahexaenoic acid |

| EFAs | = Essential fatty acids |

| EPA | = Eicosapentaenoic acid |

| EDP | = Epoxydocosapentaenoic acid |

| EEQ | = Epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid |

| GLA | = γ-linolenic acid |

| GPR40 | = G-protein-coupled receptor 40 |

| LA | = linoleic acid |

| LOX | = Lipoxygenase |

| M3G | = Morphine-3-glucuronide |

| M6G | = Morphine-6-glucuronide |

| PLA2 | = Phospholipase A2 |

| omega-3 PUFAs | = Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| omega-6 PUFAs | = Omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RvE1 | = Resolvin E-series 1 |

| RvE2) | = Resolvin E-series 2 |

| RvD1 | = Resolvin D-series 1 |

| RvD2 | = Resolvin D-series 2 |

| TRPV1 | = Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid type 1 |

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author confirms that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from Universidad Nacional de La Rioja, Argentina. I thank Dr. Paul Hobson, native speaker, for revision of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

| [1] | Wertheimer, A.I.; Levy, R.; O’Connor, T.W. Too many drugs? The clinical and economic value of incremental innovations. The clinical and economic value of incremental innovations. In: Investing in Health:, 2001, 14, 77-117. The Social and Economic Benefits of Health Care Innovation 2001 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0194-3960(01)14005-9] |

| [2] | Wertheimer, A.I.; Morrison, A. Combination Drugs: Innovation in Pharmacotherapy. P&T, 2002, 27, 1. |

| [3] | Smith, H.S. Combination opioid analgesics. Pain Physician, 2008, 11(2), 201-214. [PMID: 18354712] |

| [4] | Portenoy, R.K. Adjuvant analgesic agents. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am., 1996, 10(1), 103-119. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70329-4] [PMID: 8821562] |

| [5] | Kanavos, P. The rising burden of cancer in the developing world. Ann. Oncol., 2006, 17(Suppl. 8), i15-, i23. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdl983] [PMID: 16801335] |

| [6] | Paice, J.A. Chronic treatment-related pain in cancer survivors. Pain, 2011, 152(3)(Suppl.), S84-S89. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.010] [PMID: 21036475] |

| [7] | Donnelly, S.; Walsh, D. The symptoms of advanced cancer. Semin. Oncol., 1995, 22(2)(Suppl. 3), 67-72. [PMID: 7537907] |

| [8] | Turk, D.C.; Wilson, H.D.; Cahana, A. Treatment of chronic non-cancer pain. Lancet, 2011, 377(9784), 2226-2235. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60402-9] [PMID: 21704872] |

| [9] | Stjernswärd, J. WHO cancer pain relief programme. Cancer Surv., 1988, 7(1), 195-208. [PMID: 2454740] |

| [10] | Bruera, E.; Palmer, J.L.; Bosnjak, S.; Rico, M.A.; Moyano, J.; Sweeney, C.; Strasser, F.; Willey, J.; Bertolino, M.; Mathias, C.; Spruyt, O.; Fisch, M.J. Methadone versus morphine as a first-line strong opioid for cancer pain: a randomized, double-blind study. J. Clin. Oncol., 2004, 22(1), 185-192. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.03.172] [PMID: 14701781] |

| [11] | Cancer Pain Relief, 2nd ed; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2015. |

| [12] | McQuay, H. Opioids in pain management. Lancet, 1999, 353(9171), 2229-2232. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03528-X] [PMID: 10393001] |

| [13] | Manchikanti, L.; Singh, A. Therapeutic opioids: a ten-year perspective on the complexities and complications of the escalating use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids. Pain Physician, 2008, 11(2)(Suppl.), S63-S88. [PMID: 18443641] |

| [14] | Thielke, S.M.; Simoni-Wastila, L.; Edlund, M.J.; DeVries, A.; Martin, B.C.; Braden, J.B.; Fan, M.Y.; Sullivan, M.D. Age and sex trends in long-term opioid use in two large American health systems between 2000 and 2005. Pain Med., 2010, 11(2), 248-256. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00740.x] [PMID: 20002323] |

| [15] | Chou, R.; Huffman, L.H. Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med., 2007, 147(7), 505-514. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00008] [PMID: 17909211] |

| [16] | Eisenberg, E.; McNicol, E.D.; Carr, D.B. Efficacy and safety of opioid agonists in the treatment of neuropathic pain of nonmalignant origin: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA, 2005, 293(24), 3043-3052. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.24.3043] [PMID: 15972567] |

| [17] | Kalso, E.; Edwards, J.E.; Moore, R.A.; McQuay, H.J. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain, 2004, 112(3), 372-380. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.019] [PMID: 15561393] |

| [18] | Dumas, E.O.; Pollack, G.M. Opioid tolerance development: a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic perspective. AAPS J., 2008, 10(4), 537-551. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1208/s12248-008-9056-1] [PMID: 18989788] |

| [19] | Franklin, GM Opioids for chronic noncancer pain A position paper of the American Academy of Neurology, 2014. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000839] |

| [20] | Trang, T.; Quirion, R.; Jhamandas, K. The spinal basis of opioid tolerance and physical dependence: Involvement of calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P, and arachidonic acid-derived metabolites. Peptides, 2005, 26(8), 1346-1355. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.031] [PMID: 16042975] |

| [21] | Smith, H.S. Opioid metabolism. Mayo Clin. Proc., 2009, 84(7), 613-624. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60750-7] [PMID: 19567715] |

| [22] | Biella, G.; Panara, C.; Pecile, A.; Sotgiu, M.L. Facilitatory role of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) on excitation induced by substance P (SP) and noxious stimuli in rat spinal dorsal horn neurons. An iontophoretic study in vivo. Brain Res., 1991, 559(2), 352-356. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(91)90024-P] [PMID: 1724408] |

| [23] | Cridland, R.A.; Henry, J.L. Intrathecal administration of CGRP in the rat attenuates a facilitation of the tail flick reflex induced by either substance P or noxious cutaneous stimulation. Neurosci. Lett., 1989, 102(2-3), 241-246. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-3940(89)90085-2] [PMID: 2478930] |

| [24] | Foran, SE; Carr, DB; Lipkowski, AW; Maszczynska, I; Marchand, JE; Misicka, A; Beinborn, M; Kopin, AS; Kream, RM Inhibition of morphine tolerance development by a substance P-opioid peptide chimera. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 2000, 295 (3)(3), 1142-8. Dec |

| [25] | Powell, K.J.; Ma, W.; Sutak, M.; Doods, H.; Quirion, R.; Jhamandas, K. Blockade and reversal of spinal morphine tolerance by peptide and non-peptide calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonists. Br. J. Pharmacol., 2000, 131(5), 875-884. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0703655] [PMID: 11053206] |

| [26] | Marriott, D.; Wilkin, G.P.; Coote, P.R.; Wood, J.N. Eicosanoid synthesis by spinal cord astrocytes is evoked by substance P; possible implications for nociception and pain. Adv. Prostaglandin Thromboxane Leukot. Res., 1991, 21B, 739-741. [PMID: 1705083] |

| [27] | Marriott, D.R.; Wilkin, G.P.; Wood, J.N. Substance P-induced release of prostaglandins from astrocytes: regional specialisation and correlation with phosphoinositol metabolism. J. Neurochem., 1991, 56(1), 259-265. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02590.x] [PMID: 1702831] |

| [28] | Hua, X.Y.; Chen, P.; Marsala, M.; Yaksh, T.L. Intrathecal substance P-induced thermal hyperalgesia and spinal release of prostaglandin E2 and amino acids. Neuroscience, 1999, 89(2), 525-534. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00488-6] [PMID: 10077333] |

| [29] | Dirig, D.M.; Yaksh, T.L. In vitro prostanoid release from spinal cord following peripheral inflammation: effects of substance P, NMDA and capsaicin. Br. J. Pharmacol., 1999, 126(6), 1333-1340. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0702427] [PMID: 10217526] |

| [30] | Malmberg, A.B.; Yaksh, T.L. Antinociceptive actions of spinal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents on the formalin test in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 1992, 263(1), 136-146. [PMID: 1403779] |

| [31] | Southall, M.D.; Michael, R.L.; Vasko, M.R. Intrathecal NSAIDS attenuate inflammation-induced neuropeptide release from rat spinal cord slices. Pain, 1998, 78(1), 39-48. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00113-4] [PMID: 9822210] |

| [32] | Vasko, M.R. Prostaglandin-induced neuropeptide release from spinal cord. Prog. Brain Res., 1995, 104, 367-380. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(08)61801-4] [PMID: 8552780] |

| [33] | Vasko, M.R.; Campbell, W.B.; Waite, K.J. Prostaglandin E2 enhances bradykinin-stimulated release of neuropeptides from rat sensory neurons in culture. J. Neurosci., 1994, 14(8), 4987-4997. [PMID: 7519258] |

| [34] | Trang, T.; McNaull, B.; Quirion, R.; Jhamandas, K. Involvement of spinal lipoxygenase metabolites in hyperalgesia and opioid tolerance. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 2004, 491(1), 21-30. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.022] [PMID: 15102529] |

| [35] | Christrup, L.L. Morphine metabolites. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand., 1997, 41(1 Pt 2), 116-122. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04625.x] [PMID: 9061094] |

| [36] | Smith, M.T. Neuroexcitatory effects of morphine and hydromorphone: evidence implicating the 3-glucuronide metabolites. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol., 2000, 27(7), 524-528. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03290.x] [PMID: 10874511] |

| [37] | Baldini, A.; Von Korff, M.; Lin, E.H. A Review of Potential Adverse Effects of Long-Term Opioid Therapy: A Practitioners Guide. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord., 2012, 14(3), 1013. [PMID: 23106029] |

| [38] | Opioid analgesic therapy. In: Doyle, D.; Hanks, G.W.; MacDonald, N., Eds.; Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, 2nd ed; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 1998; pp. 331-335. |

| [39] | Smith, H.S.; Laufer, A. Opioid induced nausea and vomiting. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 2014, 722(5), 67-78. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.09.074] [PMID: 24157979] |

| [40] | Byas-Smith, M.G.; Chapman, S.L.; Reed, B.; Cotsonis, G. The effect of opioids on driving and psychomotor performance in patients with chronic pain. Clin. J. Pain, 2005, 21(4), 345-352. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.ajp.0000125244.29279.c1] [PMID: 15951653] |

| [41] | Jovey, R.D.; Ennis, J.; Gardner-Nix, J.; Goldman, B.; Hays, H.; Lynch, M.; Moulin, D. Use of opioid analgesics for the treatment of chronic noncancer paina consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society, 2002. Pain Res. Manag., 2003, 8(Suppl. A), 3A-28A. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2003/436716] [PMID: 14685304] |

| [42] | Coupe, M.H.; Stannard, C. Opioids in persistent non-cancer pain. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia. Critical Care and Pain, 2007, 7(3), 100-103. |

| [43] | Bruera, E.; Miller, M.J.; Macmillan, K.; Kuehn, N. Neuropsychological effects of methylphenidate in patients receiving a continuous infusion of narcotics for cancer pain. Pain, 1992, 48(2), 163-166. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(92)90053-E] [PMID: 1589233] |

| [44] | Wilwerding, M.B.; Loprinzi, C.L.; Mailliard, J.A.; OFallon, J.R.; Miser, A.W.; van Haelst, C.; Barton, D.L.; Foley, J.F.; Athmann, L.M. A randomized, crossover evaluation of methylphenidate in cancer patients receiving strong narcotics. Support. Care Cancer, 1995, 3(2), 135-138. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00365854] [PMID: 7539701] |

| [45] | Bruera, E.; Chadwick, S.; Brenneis, C.; Hanson, J.; MacDonald, R.N. Methylphenidate associated with narcotics for the treatment of cancer pain. Cancer Treat. Rep., 1987, 71(1), 67-70. [PMID: 3791269] |

| [46] | Reissig, J.E.; Rybarczyk, A.M. Pharmacologic treatment of opioid-induced sedation in chronic pain. Ann. Pharmacother., 2005, 39(4), 727-731. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1345/aph.1E309] [PMID: 15755795] |

| [47] | Ahmedzai, S. New approaches to pain control in patients with cancer. Eur. J. Cancer, 1997, 33(Suppl. 6), S8-S14. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00205-0] [PMID: 9404234] |

| [48] | Swegle, J.M.; Logemann, C. Management of common opioid-induced adverse effects. Am. Fam. Physician, 2006, 74(8), 1347-1354. [PMID: 17087429] |

| [49] | Schug, S.A.; Garrett, W.R.; Gillespie, G. Opioid and non-opioid analgesics. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol., 2003, 17(1), 91-110. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/bean.2003.0267] [PMID: 12751551] |

| [50] | Mori, T.; Shibasaki, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Shibasaki, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Wang, E.; Masukawa, D.; Yoshizawa, K.; Horie, S.; Suzuki, T. Mechanisms that underlie μ-opioid receptor agonist-induced constipation: differential involvement of μ-opioid receptor sites and responsible regions. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 2013, 347(1), 91-99. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/jpet.113.204313] [PMID: 23902939] |

| [51] | Camilleri, M. Opioid-induced constipation: challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 2011, 106(5), 835-842. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2011.30] [PMID: 21343919] |

| [52] | Recommendations for the appropriate use of opioids for persistent non-cancer pain. A consensus statement prepared on behalf of the Pain Society, the Royal College of Anaesthetists, the Royal College of General Practitioners and the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Ed. The Pain Society. March 2004. Available from: http://www.anaesthesiauk.com/documents/opioids_doc_2004.pdf, 2004. |

| [53] | Coupe, M.H.; Stannard, C. Opioids in persistent non-cancer pain. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia. Critical Care and Pain, 2007, 7(3), 100-103. |

| [54] | Cherny, N.J.; Chang, V.; Frager, G.; Ingham, J.M.; Tiseo, P.J.; Popp, B.; Portenoy, R.K.; Foley, K.M.; Foley, K.M. Opioid pharmacotherapy in the management of cancer pain: a survey of strategies used by pain physicians for the selection of analgesic drugs and routes of administration. Cancer, 1995, 76(7), 1283-1293. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19951001)76:7<1283::AID-CNCR2820760728>3.0.CO;2-0] [PMID: 8630910] |

| [55] | Plummer, J.L.; Owen, H.; Ilsley, A.H.; Tordoff, K. Sustained-release ibuprofen as an adjunct to morphine patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth. Analg., 1996, 83(1), 92-96. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199607000-00016] [PMID: 8659772] |

| [56] | Schug, S.A.; Sidebotham, D.A.; McGuinnety, M.; Thomas, J.; Fox, L. Acetaminophen as an adjunct to morphine by patient-controlled analgesia in the management of acute postoperative pain. Anesth. Analg., 1998, 87(2), 368-372. [PMID: 9706932] |

| [57] | Tesfaye, S.; Selvarajah, D. Morphine, gabapentin, or their combination for neuropathic pain. N. Engl. J. Med., 2005, 352(25), 2650-2651. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200506233522520] [PMID: 15981312] |

| [58] | Ossipov, M.H.; Malseed, R.T.; Goldstein, F.J. Augmentation of central and peripheral morphine analgesia by desipramine. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther., 1982, 259(2), 222-229. [PMID: 7181579] |

| [59] | De Kock, M.F.; Pichon, G.; Scholtes, J.L. Intraoperative clonidine enhances postoperative morphine patient-controlled analgesia. Can. J. Anaesth., 1992, 39(6), 537-544. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03008314] [PMID: 1643675] |

| [60] | Goldstein, F.J. Adjuncts to opioid therapy. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc., 2002, 102(9)(Suppl. 3), S15-S21. [PMID: 12356036] |

| [61] | Laguerre, P.J. Alternatives and adjuncts to opioids for the treatment of chronic pain. N. C. Med. J., 2013, 74(3), 209-214. [PMID: 23940888] |

| [62] | Sulindro-Ma, M. Audette , JF; Bailey, A. Nutrition and supplements for pain management, Integrative pain medicine; Humana Press: USA, 2008, pp. 417-445. |

| [63] | Visioli, F.; Poli, A.; Richard, D.; Paoletti, R. Modulation of inflammation by nutritional interventions. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep., 2008, 10(6), 451-453. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11883-008-0069-0] [PMID: 18937889] |

| [64] | Minton, K. Inflammasome: fishing for anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Immunol., 2013, 13(8), 545. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nri3498] [PMID: 23846115] |

| [65] | Simopoulos, A.P. Evolutionary aspects of diet and essential fatty acids. In: Fatty Acids and Lipids-New Findings; Hamazaki, T.; Okuyama, H., Eds.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2001; Vol. 88, pp. 18-27. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000059742] |

| [66] | Arterburn, L.M.; Hall, E.B.; Oken, H. Distribution, interconversion, and dose response of n-3 fatty acids in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2006, 83(6)(Suppl.), 1467S-1476S. [PMID: 16841856] |

| [67] | Vermunt, S.H.; Mensink, R.P.; Simonis, M.M.; Hornstra, G. Effects of dietary alpha-linolenic acid on the conversion and oxidation of 13C-alpha-linolenic acid. Lipids, 2000, 35(2), 137-142. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02664762] [PMID: 10757543] |

| [68] | Burdge, G.C.; Wootton, S.A. Conversion of alpha-linolenic acid to eicosapentaenoic, docosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids in young women. Br. J. Nutr., 2002, 88(4), 411-420. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/BJN2002689] [PMID: 12323090] |

| [69] | Burdge, G.C.; Finnegan, Y.E.; Minihane, A.M.; Williams, C.M.; Wootton, S.A. Effect of altered dietary n-3 fatty acid intake upon plasma lipid fatty acid composition, conversion of [13C]alpha-linolenic acid to longer-chain fatty acids and partitioning towards beta-oxidation in older men. Br. J. Nutr., 2003, 90(2), 311-321. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/BJN2003901] [PMID: 12908891] |

| [70] | Burdge, G.C.; Jones, A.E.; Wootton, S.A. Eicosapentaenoic and docosapentaenoic acids are the principal products of alpha-linolenic acid metabolism in young men. Br. J. Nutr., 2002, 88(4), 355-363. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/BJN2002662] [PMID: 12323085] |

| [71] | Gerster, H. Can adults adequately convert alpha-linolenic acid (18:3n-3) to eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n-3)? Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res., 1998, 68(3), 159-173. [PMID: 9637947] |

| [72] | Burdge, G. Alpha-linolenic acid metabolism in men and women: nutritional and biological implications. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care, 2004, 7(2), 137-144. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00075197-200403000-00006] [PMID: 15075703] |

| [73] | Pawlosky, R.J.; Hibbeln, J.R.; Lin, Y.; Goodson, S.; Riggs, P.; Sebring, N.; Brown, G.L.; Salem, N., Jr Effects of beef- and fish-based diets on the kinetics of n-3 fatty acid metabolism in human subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2003, 77(3), 565-572. [PMID: 12600844] |

| [74] | Goyens, P.L.; Spilker, M.E.; Zock, P.L.; Katan, M.B.; Mensink, R.P. Compartmental modeling to quantify alpha-linolenic acid conversion after longer term intake of multiple tracer boluses. J. Lipid Res., 2005, 46(7), 1474-1483. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M400514-JLR200] [PMID: 15834128] |

| [75] | Das, U.N. Biological significance of essential fatty acids. J. Assoc. Physicians India, 2006, 54, 309-319. [PMID: 16944615] |

| [76] | Simopoulos, A.P. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed. Pharmacother., 2002, 56(8), 365-379. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0753-3322(02)00253-6] [PMID: 12442909] |

| [77] | Simopoulos, A.P. Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune diseases. J. Am. Coll. Nutr., 2002, 21(6), 495-505. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2002.10719248] [PMID: 12480795] |

| [78] | Kang, J.X. The importance of omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cell function. The gene transfer of omega-3 fatty acid desaturase. In: Omega-6/Omega-3 Essential Fatty Acid Ratio: The Scientific Evidence; Simopoulos, A.P.; Cleland, L.G., Eds.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2003; Vol. 92, pp. 23-36. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000073790] |

| [79] | Calder, P.C. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: nutrition or pharmacology? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol., 2013, 75(3), 645-662. [PMID: 22765297] |

| [80] | Patterson, E; Wall, R; Fitzgerald, GF; Ross, RP; Stanton, C Health Implications of High Dietary Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. J. Nutr. Metab., 2012, 75(3), 539-426. |

| [81] | Goldberg, R.J.; Katz, J. A meta-analysis of the analgesic effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for inflammatory joint pain. Pain, 2007, 129(1-2), 210-223. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.020] [PMID: 17335973] |

| [82] | Pérez, J.; Ware, M.A.; Chevalier, S.; Gougeon, R.; Shir, Y. Dietary omega-3 fatty acids may be associated with increased neuropathic pain in nerve-injured rats. Anesth. Analg., 2005, 101(2), 444-448. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000158469.11775.52] [PMID: 16037160] |

| [83] | Stenson, W.F.; Cort, D.; Rodgers, J.; Burakoff, R.; DeSchryver-Kecskemeti, K.; Gramlich, T.L.; Beeken, W. Dietary supplementation with fish oil in ulcerative colitis. Ann. Intern. Med., 1992, 116(8), 609-614. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-116-8-609] [PMID: 1312317] |

| [84] | Ramsden, C.E.; Faurot, K.R.; Zamora, D.; Palsson, O.S.; Maclntosh, B.A.; Gaylord, S.; Taha, A.Y.; Rapport, S.I.; Hibbeln, J.R.; Davis, J.M.; Mann, J.D. Targeted alteration of dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids for the treatment of chronic headaches: a randomized trial. Pain, 2015, 156(4), 587-596. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460348.84965.47] [PMID: 25790451] |

| [85] | Hill, C.L.; March, L.M.; Aitken, D.; Lester, S.E.; Battersby, R.; Hynes, K.; Fedorova, T.; Proudman, S.M.; James, M.; Cleland, L.G.; Jones, G. Fish oil in knee osteoarthritis: a randomised clinical trial of low dose versus high dose. Ann. Rheum. Dis., 2016, 75(1), 23-29. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207169] [PMID: 26353789] |

| [86] | Torres-Guzman, A.M.; Morado-Urbina, C.E.; Alvarado-Vazquez, P.A.; Acosta-Gonzalez, R.I.; Chávez-Piña, A.E.; Montiel-Ruiz, R.M.; Jimenez-Andrade, J.M. Chronic oral or intraarticular administration of docosahexaenoic acid reduces nociception and knee edema and improves functional outcomes in a mouse model of Complete Freunds Adjuvant-induced knee arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther., 2014, 16(2), R64. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/ar4502] [PMID: 24612981] |

| [87] | Maroon, J.C.; Bost, J.W. Omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil) as an anti-inflammatory: an alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for discogenic pain. Surg. Neurol., 2006, 65(4), 326-331. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surneu.2005.10.023] [PMID: 16531187] |

| [88] | Berbert, A.A.; Kondo, C.R.; Almendra, C.L.; Matsuo, T.; Dichi, I. Supplementation of fish oil and olive oil in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition, 2005, 21(2), 131-136. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2004.03.023] [PMID: 15723739] |