- Home

- About Journals

-

Information for Authors/ReviewersEditorial Policies

Publication Fee

Publication Cycle - Process Flowchart

Online Manuscript Submission and Tracking System

Publishing Ethics and Rectitude

Authorship

Author Benefits

Reviewer Guidelines

Guest Editor Guidelines

Peer Review Workflow

Quick Track Option

Copyediting Services

Bentham Open Membership

Bentham Open Advisory Board

Archiving Policies

Fabricating and Stating False Information

Post Publication Discussions and Corrections

Editorial Management

Advertise With Us

Funding Agencies

Rate List

Kudos

General FAQs

Special Fee Waivers and Discounts

- Contact

- Help

- About Us

- Search

The Open Bioactive Compounds Journal

(Discontinued)

ISSN: 1874-8473 ― Volume 9, 2020

Multifunctional Antioxidant Activities of Alkyl Gallates

Isao Kubo*, Noriyoshi Masuoka, Tae Joung Ha, Kuniyoshi Shimizu, Ken-ichi Nihei

Abstract

A series (C1 to C16) of alkyl gallates was tested for their antioxidant activity for food protection and human health. One molecule of alkyl gallate, regardless of alkyl chain length, scavenges six molecules of 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH). Alkyl gallates inhibited the linoleic acid peroxidation catalyzed by soybean lipoxygenase-1 (EC 1.13.11.12, Type 1) without being oxidized. The progress curves for enzyme reactions were recorded by both spectrophotometric and polarographic methods and the inhibitory activity was a parabolic function of their lipophilicity (log P) and maximized with alkyl chain length between C12 and C16. Tetradecanyl (C14) gallate exhibited the most potent inhibition with an IC50 of 0.06 µM. The inhibition kinetics of dodecyl gallate (C12) revealed competitive and slow-binding inhibition. Alkyl gallates chelate transition metal ions and this chelation ability should be of considerable advantage as antioxidants. Additionally, gallic acid was found to inhibit superoxide anion generated by xanthine oxidase (EC 1.1.3.22) but did not inhibit enzymatically catalyzed uric acid formation.

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2010Volume: 3

First Page: 1

Last Page: 11

Publisher Id: TOBCJ-3-1

DOI: 10.2174/1874847301003010001

Article History:

Received Date: 14/4/2009Revision Received Date: 13/5/2009

Acceptance Date: 20/5/2009

Electronic publication date: 27/1/2010

Collection year: 2010

open-access license: This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted, non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the work is properly cited.

* Address correspondence to this author at the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-3114, USA; Tel: +1-510-643-6303; Fax: +1-510-643-0215; E-mail: ikubo@berkeley.edu

| Open Peer Review Details | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Manuscript submitted on 14-4-2009 |

Original Manuscript | Multifunctional Antioxidant Activities of Alkyl Gallates | |

1. INTRODUCTION

Antioxidants in foods normally refer to substances that can inhibit fatty acid autoxidation. The major antioxidants are metal chelators (preventive) and chain-breaking antioxidants (sacrificial) acting as hydrogen atom donors [1Serrano A, Palacios C, Roy G, et al. Derivatives of gallic acid induce apoptosis in tumoral cell lines and inhibit lymphocyte proliferation Arch Biochem Biophys 1998; 350: 49-54., 2Huang D, Ou B, Prior R. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays J Agric Food Chem 2005; 53: 1841-56.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf030723c] [PMID: 15769103] ]. Propyl, octyl and dodecyl (lauryl) gallates are currently permitted for use as antioxidant additives in food [3Aruoma OI, Murcia A, Butler J, Halliwell B. Evaluation of the antioxidant and prooxidant actions of gallic acid and its derivatives J Agric Food Chem 1993; 41: 1880-5.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00035a014] ]. Hence, the previous studies usually emphasized their scavenging activity to use them as antioxidant additives in food. In addition to use them as antioxidant activities, we recently proposed that various multifunctional food additives such as a series of alkyl gallates, can be designed by selection of appropriate head and tail portions [4Kubo I, Xiao P, Nihei K, Fujita K, Yamagiwa Y, Kamikawa T. Molecular design of antifungal agents J Agric Food Chem 2002; 50: 3992-8.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf020088v] [PMID: 12083872] ] since the balance of these two is related to many biological activities. However, the rationale for this observation, especially the role of the hydrophobic portion, is still poorly understood. The head and tail structures are synthetically easily accessible as an ester and therefore the construction of a wide range of structurally diverse multifunctional mimics are available for evaluation. However, selection of head and tail building blocks need to be concerned not only for food protection but also for their benefits to human health after their consumption. This prompted us to design antioxidative antimicrobial agents as an example [5Kubo I, Chen Q X, Nihei K. Molecular design of antibrowning agents: Antioxidative tyrosinase inhibitors Food Chem 2003; 81: 241-7.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00418-1] ]. For food protection, antioxidant additives acting in variety of ways including direct quenching of reactive oxygen species, inhibition of enzymes involved in the production of the reactive oxygen species, and chelation of low valent metals are needed in addition to antimicrobial activity. Lipid peroxidation is one of the major factors in deterioration during the storage and processing of foods. For example, the oxidation of membrane lipids is implicated in the development of off-flavors [6Gray JI, Pearson AM. Rancidity and warmed-over flavor Avd Meat Res 1987; 3: 221-69.], loss of fresh meat color [7Faustman C, Cassens RG, Schaefer DM, Buege DR, Williams SN, Scheller KK. Improvement of pigment and lipid stability in Holstein steer beef by dietary supplementation with

vitamin E J Food Sci 1989; 54: 858-62.], and the formation of harmful lipid peroxidation products [8Monahan FJ, Gray JI, Booren AM, et al. Influence of dietary treatment on cholesterol oxidation in pork JAgric Food Chem 1992; 40: 1310-5.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00020a003] ] in muscle foods. Addition of antioxidants has become popular as a means of increasing the shelf life of food products and of improving the stability of lipid-containing foods by preventing loss of sensory and nutritional quality [9Tsuda T, Ohshima K, Kawakishi S, Osawa T. Antioxidative pigments isolated from the seeds of Phaseolus vulgaris LJ Agric Food Chem 1994; 42: 248-51.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00038a004] ]. In living systems, the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids in biological membranes leads to a decrease in the membrane fluidity and disruption of membrane structure and function [10Machlin L, Bendich A. Free radical tissue damage: protective role of antioxidant nutrients FASEB J 1987; 1: 441-5.

[PMID: 3315807] , 11Slater TF, Cheeseman KH. Free radical mechanisms in relation to tissue injury Proc Natr Soc 1987; 46: 1-12.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/PNS19870003] [PMID: 3033678] ]. Cellular damage due to lipid peroxidation causes serious derangements, such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, coronary arteriosclerosis, and diabetes mellitus [12Sugawara H, Tobise K, Minami H, Uekita K, Yoshie H, Onodera S. Diabetes mellitus and reperfusion injury increase the level of active oxygen-induced lipid peroxidation in rat cardiac membranes J Clin Exp Med 1992; 163: 237-8., 13Kok FJ, Van Poppel G, Melse J, et al. Do antioxidants and polyunsaturated fatty acids have a combined association with coronary

arteriosclerosis? Arteriosclerosis 1991; 86: 85-90.], and it is also associated with aging and carcinogenesis [14Yagi K. Lipid peroxides and human disease Chem Phys Lipid 1987; 45: 337-41.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0009-3084(87)90071-5] ]. Hence, antioxidant development/use/selection needs to be concerned about all the processes mentioned previously. This prompted us to further examine various antioxidative activities of a series of alkyl gallates as an example.

2. RESULTS

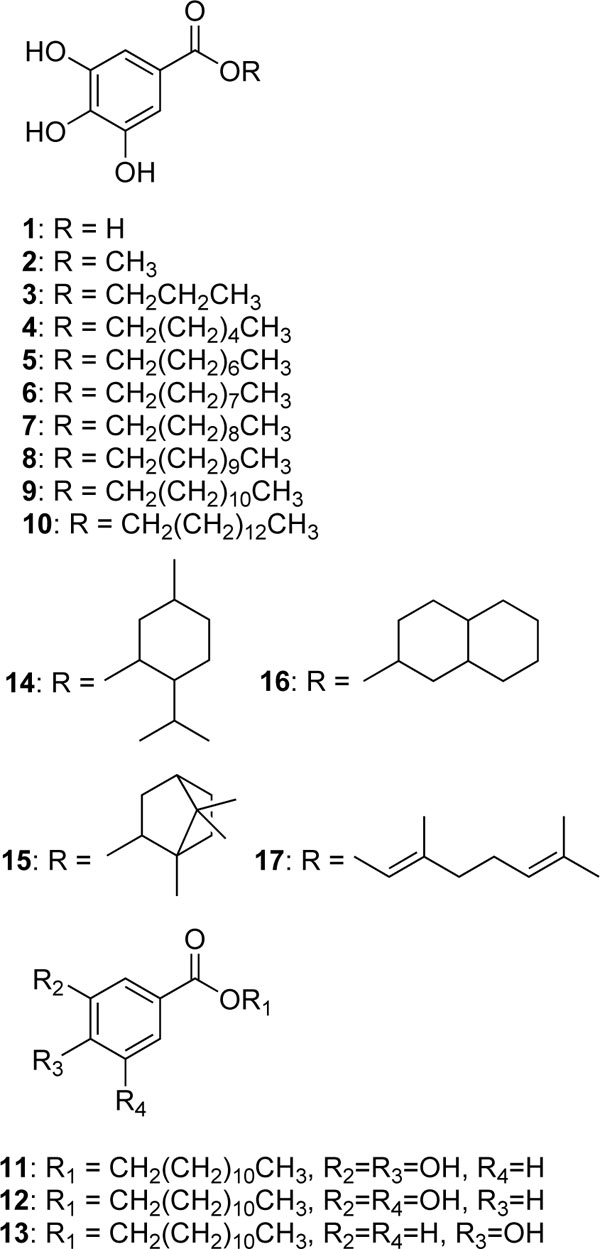

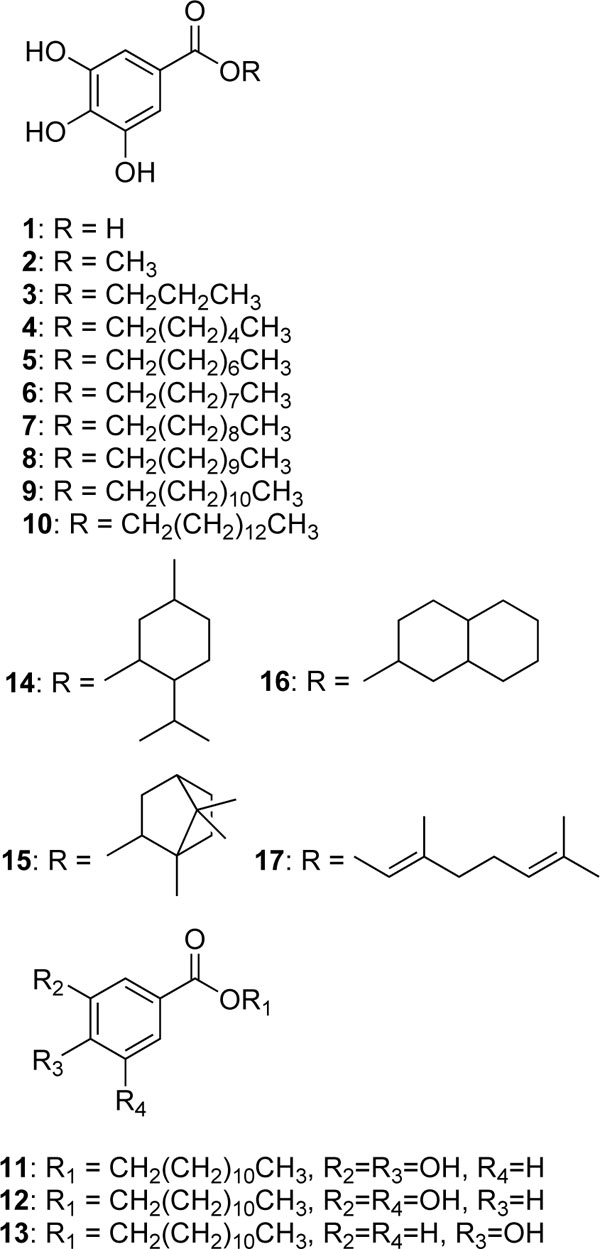

Alkyl gallates (1-17) (see Fig.1 for structures) act as antioxidants in a variety ways that include quenching reactive oxygen species, inhibiting various prooxidant enzymes involved in the production of the reactive oxygen species, and chelating divalent metal ions such as Fe2+ and Cu2+. Hence, alkyl gallates can be defined as multifunctional antioxidants. Their diverse antioxidant activities are directly or indirectly explained by their head and tail structural function, indicating that the alkenyl side chain is largely associated with the activity. The available data have been reported as the result of sporadic research, so it is time to review and summarize in one paper all what is currently known.

for structures) act as antioxidants in a variety ways that include quenching reactive oxygen species, inhibiting various prooxidant enzymes involved in the production of the reactive oxygen species, and chelating divalent metal ions such as Fe2+ and Cu2+. Hence, alkyl gallates can be defined as multifunctional antioxidants. Their diverse antioxidant activities are directly or indirectly explained by their head and tail structural function, indicating that the alkenyl side chain is largely associated with the activity. The available data have been reported as the result of sporadic research, so it is time to review and summarize in one paper all what is currently known.

|

Fig. (1) Chemical structures of gallic acids and related compounds |

2.1. Scavenging Activity

For food protection, alkyl gallates are useful as antioxidative antimicrobial agents. Gallic acid and its methyl, ethyl, propyl and n-butyl esters were previously reported to scavenge the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical [15Yoshida T, Mori K, Hatano T, et al. Studies on inhibition mechanism

of autoxidation by tannins and flavonoids V. Radical-scavenging effects of tannins and related polyphenols on 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical Chem Pharm Bull 1989; 37: 1919-21.

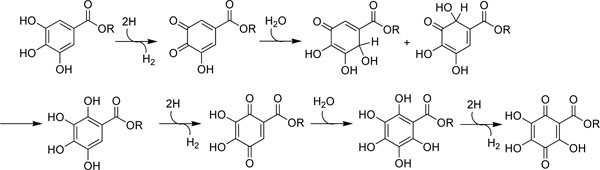

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1248/cpb.37.1919] , 16Savi LA, Leal PC, Vieira TO, et al. Evaluation of anti-herpetic and antioxidant activities, and cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of synthetic alkyl-esters of gallic acid Arztl Forsch 2005; 55: 66-75.] but these studies were not comprehensive. Hence, the radical scavenging activity on the DPPH radical, which can be measured as decolorizing activity following the trapping of the unpaired electron of DPPH, was examined first. The reaction progress absorbance of the mixture is monitored at 517 nm for 20 min and the results are listed in Table 1. Gallic acid and its series (C1-C12) of alkyl esters showed almost equally potent radical scavenging activity on DPPH radical. One molecule of alkyl gallates scavenges six DPPH molecules. Thus, alkyl gallates are oxidized three times by DPPH within 20 min as illustrated (Fig. 2 ). The scavenging activity does not correlate with the hydrophobic alkyl chain length. This is consistent with the previous report

). The scavenging activity does not correlate with the hydrophobic alkyl chain length. This is consistent with the previous report

|

Fig. (2) One molecule of alkyl gallate, regardless of its alkyl chain length, can be oxidized three times by DPPH radical into the corresponding quinone. |

[17Gunckel S, Santander P, Cordano G, et al. Antioxidant activity of gallates an electrochemical study in aqueous media Chem Biol Inter 1998; 114: 45-59.]. Hence, all the alkyl gallates can be used as scavenging antioxidants and selection of the tail portion seems to be flexible. On the other hand, their antimicrobial activity is dependent on the chain length and a broad antimicrobial spectrum should be preferred for food protection. Nonyl gallate (C9) (6) showed the most potent and broad spectrum [18Kubo I, Xiao P, Fujita K. Antifungal activity of octyl gallate: Structural criteria and mode of action Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2001; 11: 347-50.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-894X(00)00656-9] , 19Fujita K, Kubo I. Plasma membrane injury by nonyl gallate

in Saccharomyces cerevisiae J Appl Microbiol 2002; 92: 1035-42.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01614.x] [PMID: 12010543] ] followed by octyl gallate (C8) (5) [20Fujita K, Kubo I. Antifungal activity of octyl gallate Int J Food Microbiol 2002; 193-201.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00108-3] ]. Dodecyl (lauryl) gallate (C12) (9) was found to be effective on Gram-positive bacteria [21Kubo I, Fujita K, Nihei K, Masuoka N. Non-antibiotic antibacterial activity of dodecyl gallate Bioorg Med Chem 2003; 11: 573-80.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0968-0896(02)00436-4] ]. Since both octyl gallate and dodecyl gallate are currently permitted for use as antioxidant additives in food [3Aruoma OI, Murcia A, Butler J, Halliwell B. Evaluation of the antioxidant and prooxidant actions of gallic acid and its derivatives J Agric Food Chem 1993; 41: 1880-5.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00035a014] ], the next experiment was centered on these two gallates.

The trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) assay is based on the scavenging of the 2,2’-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical (ABTS·) converting it into a colorless product. The degree of decolorization induced by a compound is related to that induced by trolox, giving the TEAC value. The TEAC value for gallic acid was 3.0 mM which is appropriately the same antioxidant activity as myricitin (3.1 mM), although esterification of the carboxylate decreases the effectiveness [22Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Paganga G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acid Free Radic Biol Med 1996; 20: 933-56.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0891-5849(95)02227-9] ]. This activity of gallic acid is much weaker compared with its scavenging activity on DPPH radical by several orders of magnitude.

Lipid peroxidation is well known to be one of the major factors in deterioration of foods during storage and processing, because it can lead to the development of unpleasant rancid or off flavors as well as potentially toxic end products [23Grechkin A. Recent developments in biochemistry of the plant lipoxygenase pathway Prog Lipid Res 1998; 37: 317-52.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0163-7827(98)00014-9] , 24Min B, Ahn DU. Mechanism of lipid peroxidation in meat

and meat products - A review Food Sci Biotechnol 2005; 14: 152-63.]. Lipid peroxidation is a typical free radical oxidation and proceeds via a cyclic chain reaction [25Witting LA, Pryor W A, Eds. Vitamin E and lipid antioxidants in free-radical-initiated reactions In Free Radicals in Bilogy 1980; 4: 295-319.] and linoleic acid is specifically the target of lipid peroxidation. Effect of alkyl gallates on autoxidation of linoleic acid was tested by the ferric thiocyanate method as previously described [26Haraguchi H, Hashimoto K, Yagi A. Antioxidative substances in leaves of Polygonum hydropiper J Agric Food Chem 1992; 40: 1349-51.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00020a011] ]. In a control reaction, the production of lipid peroxide increased almost linearly during 5 days of incubation. a-Tocopherol, also known as vitamin E, inhibited the linoleic acid peroxidation almost 50% at 30 µg/mL. Both octyl gallate and dodecyl gallate almost completely inhibited this

oxidation at the same concentration, indicating that both gallates are more potent linoleic acid peroxidation inhibitors than a-tocopherol.

2.2. Inhibition of Prooxidant Enzymes

2.2.1. Lipoxygenase

Lipoxygenases (EC 1.13.11.12) are suggested to be involved in the lipid peroxidation [27Shibata D, Axelrod B. Plant lipoxygenases J Lipid Mediat Cell Signal 1995; 12: 213-28.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0929-7855(95)00020-Q] ]. Hence, lipoxygenase inhibitors should have broad applications [28Richard-Forget F, Gauillard F, Hugues M, Jean-Marc T, Boivin P, Nicolas J. Inhibition of horse bean and germinated

barley lipoxygenases by some phenolic compounds J Food Sci 1995; 60: 1325-9.]. Soybean lipoxygenase-1 is known to catalyze the oxygenation of polyenoic fatty acids containing a (1Z,4Z)-pentadiene system such as linoleic acid and linolenic acid to their 1-hydro- peroxy-(2E,4Z)-pentadiene products. In plants, the primary dioxygenation product is 13(S)-hydroperoxy-9Z,11E-octadienoic acid (13-HPOD) [29Grechkin A. Recent developments in biochemistry of the plant lipoxygenase pathway Prog Lipid Res 1998; 37: 317-52.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0163-7827(98)00014-9] ]. Hence, the enzyme assay was usually performed using a UV spectrophotometer to detect the increase at 234 nm associated with the (2E,4Z)-conjugated double bonds newly formed in the product but not the substrate. In many previous reports, the data were obtained at pH 9 since soybean lipoxygenase-1 had its optimum pH at 9.0 [30Axelrod B, Cheesbrough TM, Laakso S. Lipoxygenase from soybeans Methods Enzymol 1981; 71: 441-57.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0076-6879(81)71055-3] ], but the absorption at 234 nm suffered from unstable baseline activity of unknown origin attributable to the presence of alkyl gallates at pH 9.0. This pseudoactivity of the blank control had to be subtracted from activity of the enzyme assay, making precise measurements difficult. Hence, lipoxygenase activity was measured as described previously [31Ha TJ, Nihei K, Kubo I. Lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of octyl gallate J Agric Food Chem 2004; 52: 3177-81.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf034925k] [PMID: 15137872] ] in Tris-HCl buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.0) by the increase in absorbance at 234 nm from 30 to 90 sec after addition of the enzyme, using linoleic acid (18 µM) as a substrate. The results are listed in Table 2.

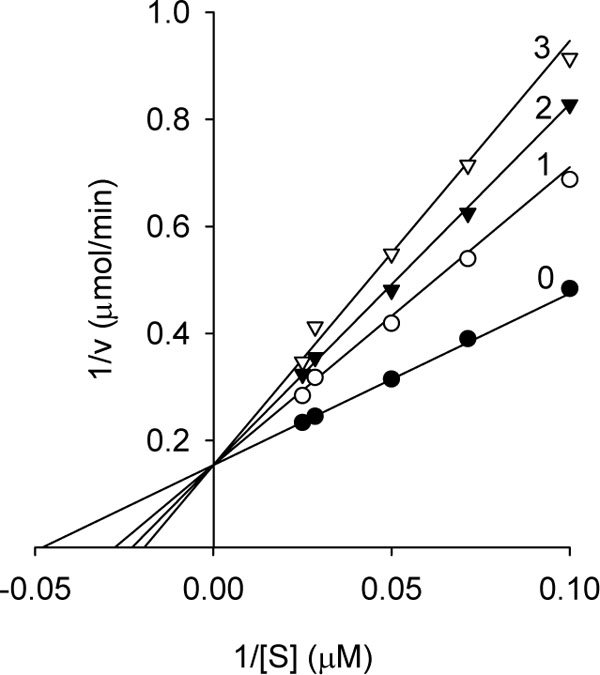

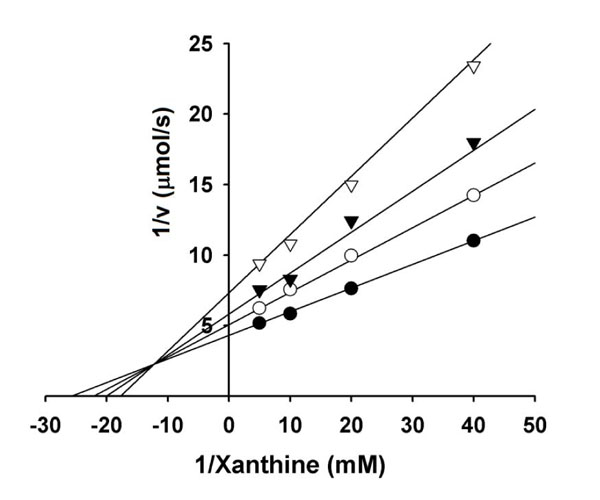

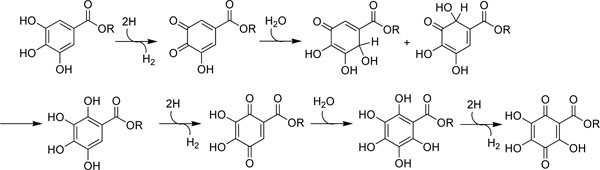

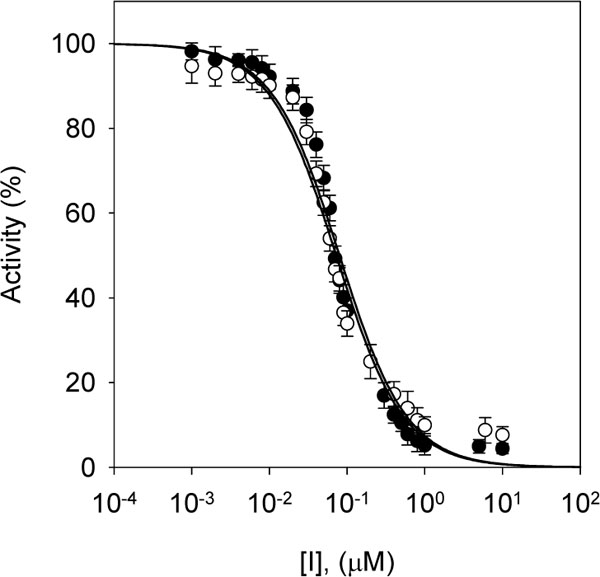

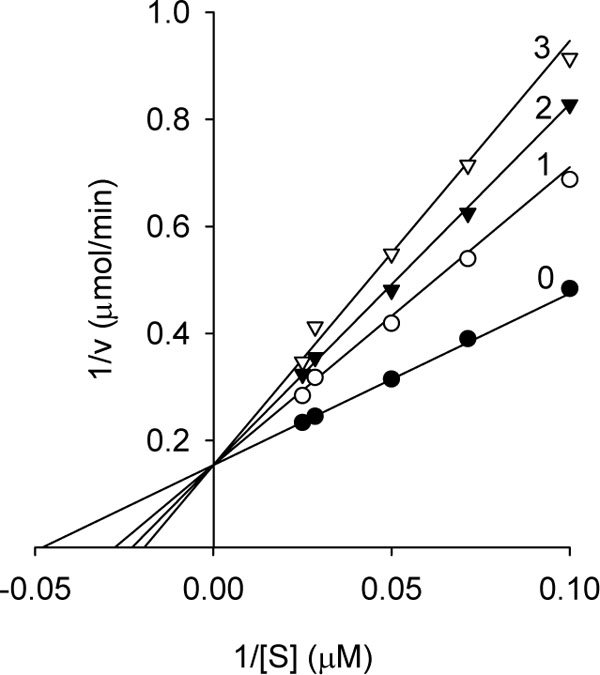

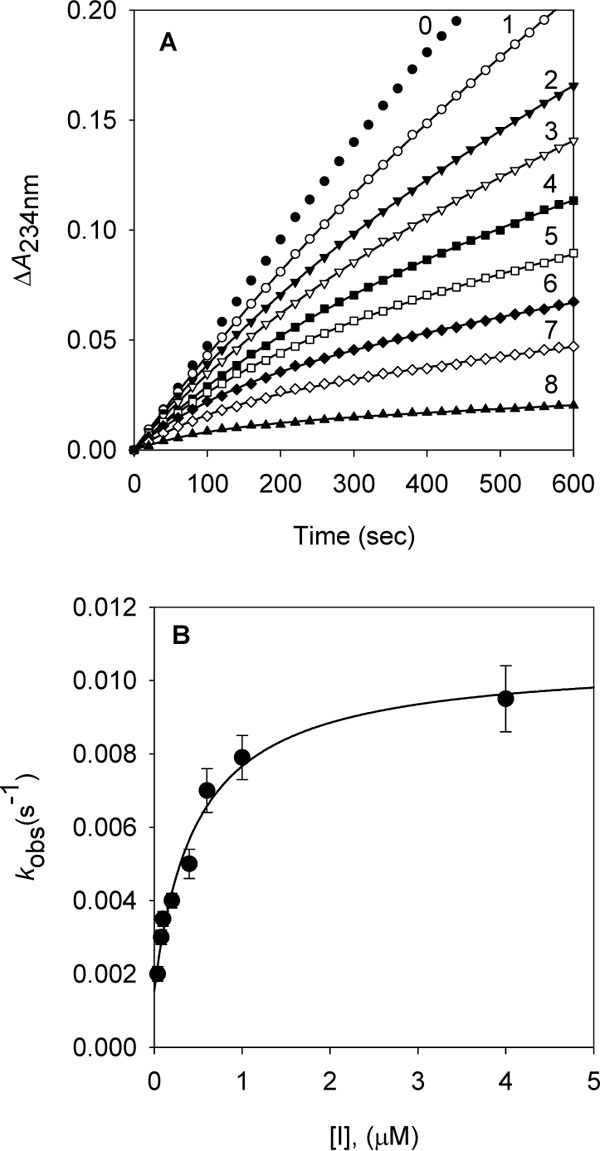

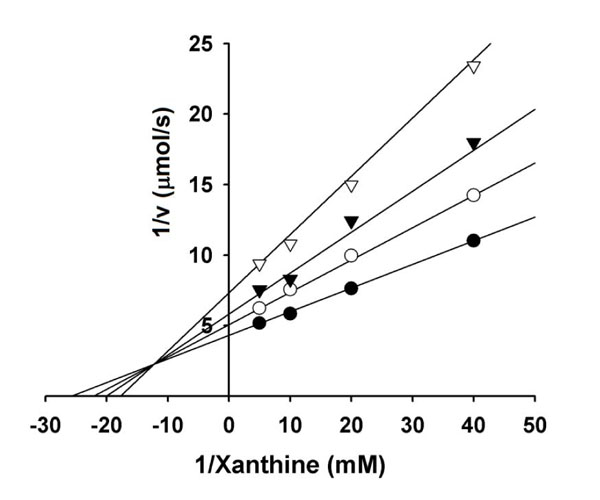

The same series of alkyl gallates (2-9) were found to inhibit the linoleic acid peroxidation catalyzed by soybean lipoxygenase-1 without being oxidized. The inhibitory activity was a parabolic function of their lipophilicity and maximized with alkyl chain length between C12 and C16. Tetradecanyl (C14) gallate exhibited the most potent inhibition with an IC50 of 0.06 µM, followed by dodecyl (C12) gallate with an IC50 of 0.07 µM (Fig. 3 ). Octyl gallate (C8) was previously described to inhibit this enzymatically catalyzed oxidation with an IC50 of 1.3 µM. The inhibition kinetics analyzed by Lineweaver-Burk plots indicates that octyl gallate is a competitive inhibitor and the inhibition constant (KI) was obtained as 0.54 µM (Fig. 4

). Octyl gallate (C8) was previously described to inhibit this enzymatically catalyzed oxidation with an IC50 of 1.3 µM. The inhibition kinetics analyzed by Lineweaver-Burk plots indicates that octyl gallate is a competitive inhibitor and the inhibition constant (KI) was obtained as 0.54 µM (Fig. 4 ) [31Ha TJ, Nihei K, Kubo I. Lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of octyl gallate J Agric Food Chem 2004; 52: 3177-81.

) [31Ha TJ, Nihei K, Kubo I. Lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of octyl gallate J Agric Food Chem 2004; 52: 3177-81.

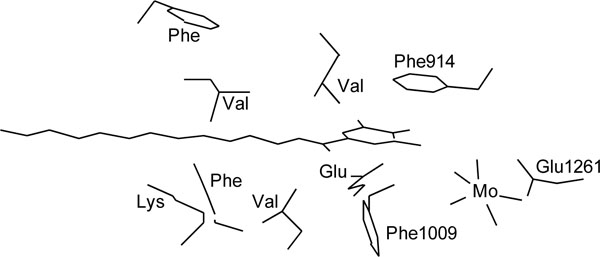

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf034925k] [PMID: 15137872] ]. The inhibition of soybean lipoxygenase-1 of longer alkyl gallates is reversible but in combination with their ability to disrupt the active site competitively and to interact with the hydrophobic portion surrounding near the active site. In the case of tetradecanyl gallate, the enzyme quickly and reversibly binds this gallate and then its tetradecanyl group undergoes a slow interaction with the hydrophobic domain (Fig. 5 , panel A). Apparently, the alkyl chain length is significantly related to the soybean lipoxygenase-1 inhibitory activity.

, panel A). Apparently, the alkyl chain length is significantly related to the soybean lipoxygenase-1 inhibitory activity.

|

Fig. (3) Effects of dodecyl gallate (closed circle: 9) and tetradecyl gallate (open triangle: 10) on the activity of soybean lipoxygenase-1 for the catalysis of linoleic acid at 25 °C. |

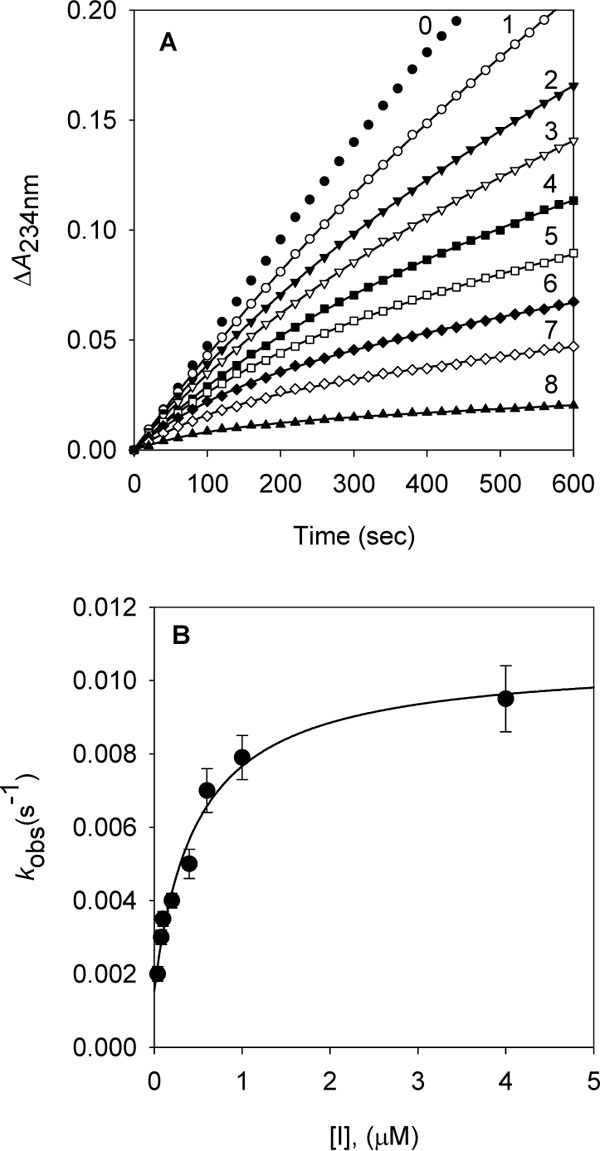

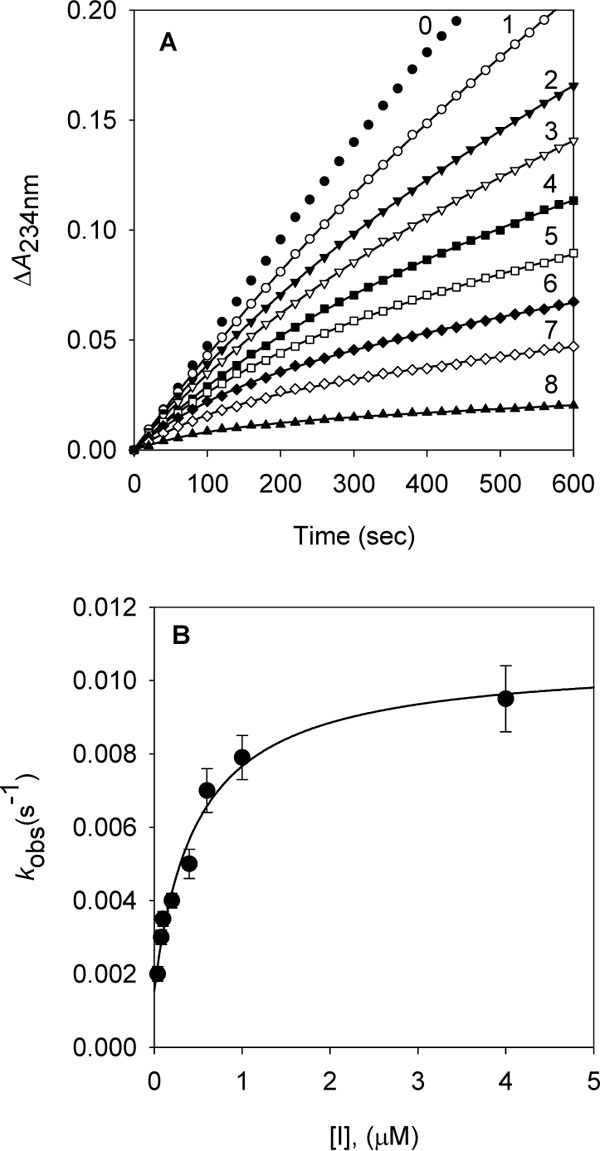

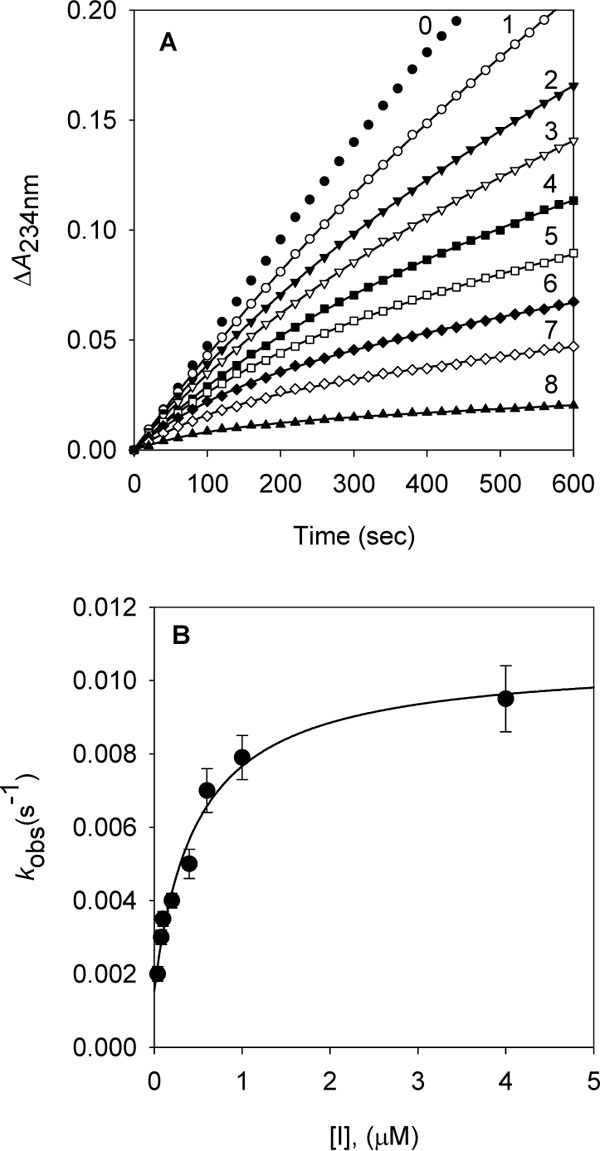

To further investigate the inhibitory effect of tetradecyl gallate (10) on dioxygenase enzyme, we assayed soybean lipoxygenase-1 activity with the inhibitor. Soybean lipoxygenase-1 showed time-dependent inhibition in the presence of dodecyl gallate (Fig.5 , panel A). Increasing tetradecyl gallate concentrations led to the decrease in both the initial velocity (vi) and the steady-state rate (vs) in the progress curve. The progress curves obtained using various concentrations of the inhibitors were fitted to eq 1 to determine vi, vs, and kobs. The plot for kobs versus [I] are shown in panel B in Fig. (5

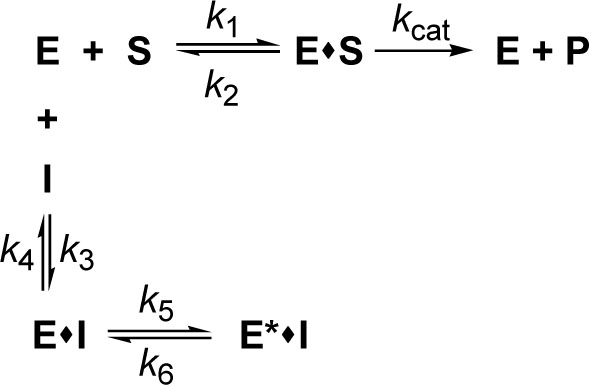

, panel A). Increasing tetradecyl gallate concentrations led to the decrease in both the initial velocity (vi) and the steady-state rate (vs) in the progress curve. The progress curves obtained using various concentrations of the inhibitors were fitted to eq 1 to determine vi, vs, and kobs. The plot for kobs versus [I] are shown in panel B in Fig. (5 ). That plot showed a hyperbolic dependence on the concentration of the tetradecyl gallate, so the inhibition of lipoxygenase-1 by tetradecyl gallate followed a mechanism as the one illustrated below. The kinetic parameters, k5, k6, and Kiapp were derived from the plots by fitting the results to eq 2. Thus, analysis of data according to eq 2 yielded the following values: k5 = 9.1(10-3 s-1, k6 = 1.5(10-3 s-1, Kiapp = 0.48 µM. The kinetic model can be written as:

). That plot showed a hyperbolic dependence on the concentration of the tetradecyl gallate, so the inhibition of lipoxygenase-1 by tetradecyl gallate followed a mechanism as the one illustrated below. The kinetic parameters, k5, k6, and Kiapp were derived from the plots by fitting the results to eq 2. Thus, analysis of data according to eq 2 yielded the following values: k5 = 9.1(10-3 s-1, k6 = 1.5(10-3 s-1, Kiapp = 0.48 µM. The kinetic model can be written as:

where E, S, I, and P denote enzyme, substrate, inhibitor (alkyl gallate) and product (13-HPOD), respectively. ES, EI and E*I are respective complexes. Because k5 is greater than k6 the enzyme first quickly and reversibly binds with tetradecyl gallate and then undergoes a slow interaction of tetradecyl group with the hydrophobic portion near the active site.

Dodecyl 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate (11) inhibited linoleic acid peroxidation catalyzed by soybean lipoxygenase-1, whereas both dodecyl 3,5-dihydroxybenzoate (12) and dodecyl 4-hydroxybenzoate (13) showed little inhibitory activity, indicating that certain head portions are needed to elicit the inhibitory activity. Thus, catechol moiety seems to be important to elicit potent soybean lipoxygenase-1 inhibitory activity as a hydrophilic head portion [28Richard-Forget F, Gauillard F, Hugues M, Jean-Marc T, Boivin P, Nicolas J. Inhibition of horse bean and germinated

barley lipoxygenases by some phenolic compounds J Food Sci 1995; 60: 1325-9., 32Whitman S, Gezginci M, Timmermann B, Holman TR. Structure-activity relationship studies of nordihydroguaiaretic acid

inhibitors toward soybean, 12-human, and 15-human lipoxygenase J Med Chem 2002; 45: 2659-61.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jm0201262] [PMID: 12036375] ]. In addition, menthyl gallate (14), bornyl gallate (15) and decahydro-2-naphthyl gallate (16) also inhibited linoleic acid peroxidation catalyzed by soybean lipoxygenase-1, indicating that the hydrophobic tail portion seems to be flexible. As mentioned above, alkyl gallates were found to possess equally potent radical scavenging activity on DPPH radical. Apparently, intermediate free radicals are formed during the catalytic cycle of lipoxygenases [33Ruddat VC, Whitman S, Holman TR, Bernasconi CF. Stopped-flow kinetics investigations of the activation of soybean lipoxygenase-1 and the influence of inhibitors on the allosteric site Biochemistry 2003; 42: 4172-8.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bi020698o] [PMID: 12680771] ], but they remain tightly bound at the active site, thus not being accessible for free radical scavengers. In summary, alkyl gallates appear to combine both lipoxygenase inhibitory activity and free radical scavenging property in one agent and thus constitute effective antioxidants.

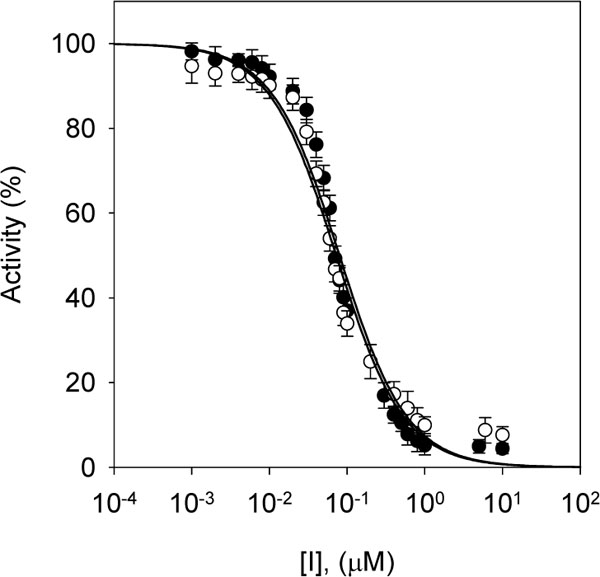

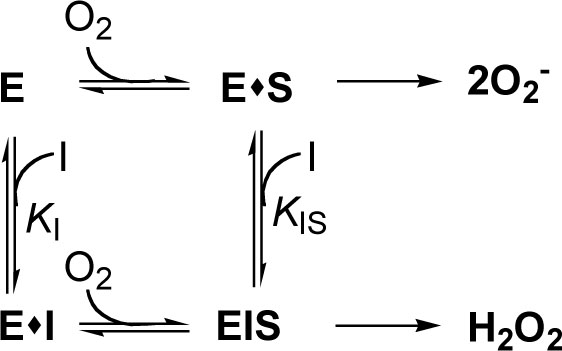

2.2.2. Xanthine Oxidase

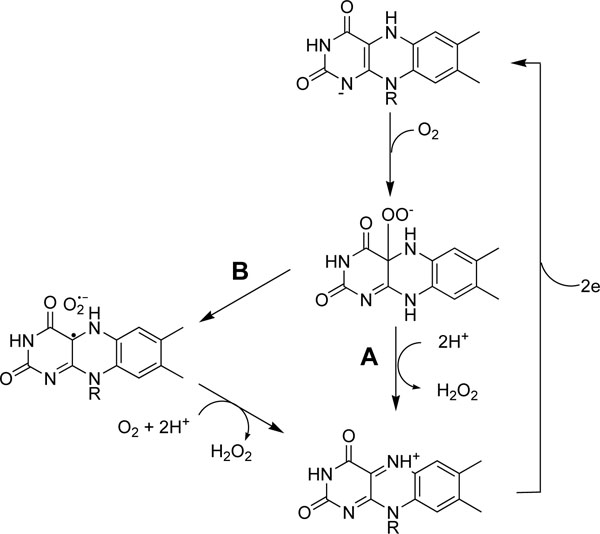

The one-electron reduction products of O2, superoxide anion (O2·-), and subsequently hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radical (HO·) derived from H2O2 and O2·-, actively participate in the initiation of lipid peroxidation. Several oxidative enzymes in the human body produce free radicals. For example, xanthine oxidase produces the O2·- radical as a normal product [34Grunfeld S, Hamilton CA, Mesaros S, et al. Rple of superoxide in the depressed nitric oxide production by the endothelium of genetically hypertensive rats Hepertesion 1995; 26: 854-7.]. In the control, superoxide anion reduces yellow nitroblue tetrazolium to blue formazan, so the generation of superoxide anion by the enzyme can be detected by measuring of the absorbance at 560 nm of formazan produced. Among the alkyl gallates tested, gallic acid was the most effective in scavenging superoxide anion generated by xanthine oxidase with an IC50 of 2.6 µM. The inhibition kinetics analyzed by Lineweaver-Burk plots shows that gallic acid is a mixed type inhibitor (Fig. 6 ) and the inhibition constants, KI and KIS were obtained as 1.5±0.2 and 2.9±0.3 µM. Xanthine oxidase is a molybdenum-containing enzyme and converts xanthine to uric acid. This enzyme-catalyzed reaction is known to proceed via transfer of an oxygen atom to xanthine from the molybdenum center. Hence, formation of uric acid was also measured. As a result, gallic acid did not inhibit xanthine oxidase up to 200 µM, indicating that its potent antioxidant activity comes from scavenging superoxide radicals or modification of xanthine oxidase. Xanthine oxidase catalyzed formation of superoxide anion or hydrogen peroxide and uric acid but the reduced oxidase only catalyzed formation of hydrogen peroxide and uric acid [35Hille R, Massey V. Studies on the oxidative half-reaction of xanthine oxidase J Biol Chem 1981; 256: 9090-5.

) and the inhibition constants, KI and KIS were obtained as 1.5±0.2 and 2.9±0.3 µM. Xanthine oxidase is a molybdenum-containing enzyme and converts xanthine to uric acid. This enzyme-catalyzed reaction is known to proceed via transfer of an oxygen atom to xanthine from the molybdenum center. Hence, formation of uric acid was also measured. As a result, gallic acid did not inhibit xanthine oxidase up to 200 µM, indicating that its potent antioxidant activity comes from scavenging superoxide radicals or modification of xanthine oxidase. Xanthine oxidase catalyzed formation of superoxide anion or hydrogen peroxide and uric acid but the reduced oxidase only catalyzed formation of hydrogen peroxide and uric acid [35Hille R, Massey V. Studies on the oxidative half-reaction of xanthine oxidase J Biol Chem 1981; 256: 9090-5.

[PMID: 6894924] ]. As the inhibition activity of superoxide anion by gallic acid was stronger than the scavenging activity of superoxide anion generated by PMS-NADH, the inhibition activity by gallic acid should comes from excursively reductive (oxidative) modification of xanthine oxidase bound by gallic acid as following scheme [36Masuoka N, Nihei K, Kubo I. Xanthine oxidase inhibitory activity of alkyl gallates Mol Nutr Food Sci 2006; 50: 725-31.]. The kinetic model can be written as:

where E, S and I denote enzyme, substrate and inhibitor (alkyl gallate), respectively. ES, EI and EIS are respective complexes.

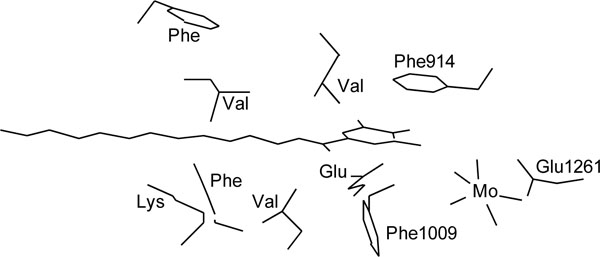

Reaction of uric acid formation by xanthine oxidase is known to proceed via transfer of an oxygen atom to xanthine from the molybdenum center. X-ray crystallographic analysis of bovine milk xanthine oxidase indicated that one can model the binding of bicyclic substrates, e.g. with Phe 1009 perpendicular to the six-membered ring of xanthine and Phe 914 stacking flat on top of the substrate’s five-membered ring, which would then be able to form a covalent bond with one of the molybdenum ligands [37Enroth C, Eger BT, Okamoto K, Nishino T, Pai EF. Crystal structures of bovine milk xanthine dehydrogenase and xanthine oxidase: Structure-based mechanism of conversion Proc Nat Acad Sci 2000; 97: 10723-8.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.20.10723] [PMID: 11005854] [PMCID: PMC27090] ]. As the present study indicated that alkyl gallates having long chains were predominantly competitive inhibitors for xanthine, we deduced that dodecyl gallate binds with Phe 1009 perpendicular to the pyrogallol moiety and Phe 914 stacking flat on top of the dodecyl group and the dodecyl chain tightly interacts with hydrophobic protein pocket to act as an anchor, which is necessary to inhibit uric acid formation, as illustrated in Fig.(7 ). To confirm this postulation, the effect of menthyl gallate (14) and bornyl gallate (15) on xanthine oxidase was examined. Neither compound inhibited uric acid formation, indicating that both can not bind to the xanthine binding site since the bulky cyclic monoterpene moieties, which are exposed on the other side of the molecules, cannot be well embraced by the hydrophobic protein pocket in xanthine binding site.

). To confirm this postulation, the effect of menthyl gallate (14) and bornyl gallate (15) on xanthine oxidase was examined. Neither compound inhibited uric acid formation, indicating that both can not bind to the xanthine binding site since the bulky cyclic monoterpene moieties, which are exposed on the other side of the molecules, cannot be well embraced by the hydrophobic protein pocket in xanthine binding site.

The inhibition of uric acid formation by alkyl gallates was further examined at different concentration of oxygen. Octyl gallate, decyl gallate and dodecyl gallate were also predominantly competitive inhibitors of oxygen. As these gallates bound to xanthine binding site of xanthine oxidase, it indicated that alkyl gallates could bind to another site, which may be oxygen binding site (or superoxide anion generation site), in xanthine oxidase.

To study the effect of gallic acid and alkyl gallates on superoxide anion generation, we examined the scavenging activity of superoxide anion by alkyl gallates since the activity was well known. Superoxide anion was non-enzymatically generated in a PMS-NADH system. The scavenging activity of alkyl gallates for superoxide anion decreased as the alkyl side chain length increased. Differences in superoxide anion scavenging activity among alkyl gallates may be explained by the fact that an alkyl gallate with a shorter alkyl chain is a smaller molecule and more water soluble which allows it to easily react with the superoxide anion. However an alkyl gallate with a long alkyl chain hardly reacts with superoxide anion at low concentration but rapidly reacts at concentrations higher than 100 µM. It may explain that at low concentration alkyl gallate with a longer chain is less water soluble to hardly react with superoxide anion but at high concentration the amphipathic gallate aggregates to form a micelle which dissolves the components of the PMS-NADH system and the gallate in the micelles easily scavenges superoxide anion generated from the system [38McGovern SL, Caselli E, Grigorieff N, Shoichet BK. A common mechanism underlying promiscuous inhibitors from

virtual and high-throughput screening J Med Chem 2002; 45: 1712-22.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jm010533y] [PMID: 11931626] ].

Effects of gallic acid and alkyl gallates on superoxide anion generation were examined under limited concentration of gallates to exclude influence of their scavenging activities. All gallates inhibited superoxide anion generation (Table 3), and the inhibition did not depend on alkyl chain length of gallates. It suggested that inhibition of superoxide anion generation with gallic acid and alkyl gallates having a short alkyl chain did not correspond to that of xanthine oxidase reaction itself. To confirm stoichiometry of xanthine oxidase reaction, oxygen consumption and hydrogen peroxide formation of the reaction were examined. No inhibition of oxygen consumption with gallic acid was observed, and the inhibition with alkyl gallates having a long chain was consistent with that of uric acid formation. No inhibition of hydrogen peroxide formation with gallic acid was also indicated. These results confirmed that gallic acid and alkyl gallates having short alkyl chain inhibited superoxide anion generation without inhibition of xanthine oxidase reaction.

Kinetic Parameters of Gallic Acid and Its Alkyl Esters for Superoxide Anion Generation by Xanthine Oxidasea)

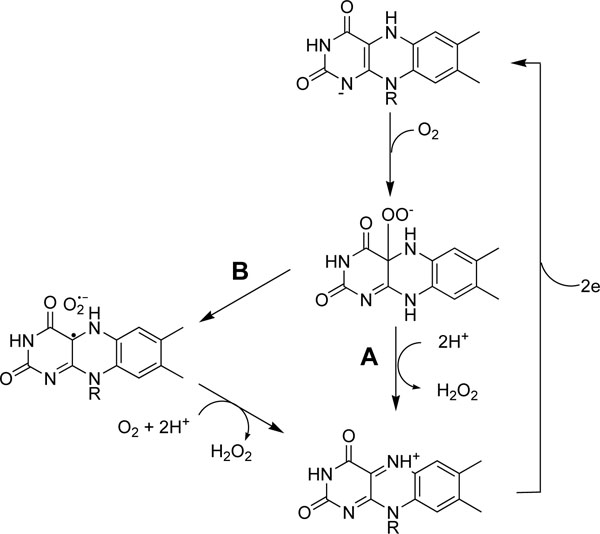

Xanthine oxidase-catalyzed reaction of oxygen to superoxide anion is known to proceed at the FAD-binding domain [37Enroth C, Eger BT, Okamoto K, Nishino T, Pai EF. Crystal structures of bovine milk xanthine dehydrogenase and xanthine oxidase: Structure-based mechanism of conversion Proc Nat Acad Sci 2000; 97: 10723-8.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.20.10723] [PMID: 11005854] [PMCID: PMC27090] ]. The binding site in the FAD-binding domain is considerably hydrophilic, and structure of the site is similar to that of vanillyl alcohol oxidase [39Fraaiji MW, van den Heuvel RHH, van Berkel WJH, Mattevi A. Structural analysis of flavinylation in vanillyl-alcohol oxidase J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 38654-8.], of which the isoalloxazine ring binds to a wide range of phenolic substrates. Compounds with a galloyl moiety bound to the isoalloxazine ring of FADH2 in squalene epoxidase [40Abe I, Seki T, Noguchi H. Potent and selective inhibition of squalene epoxidase by synthetic galloyl esters Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000; 270: 137-40.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.2000.2399] [PMID: 10733917] ]. As octyl, decyl and dodecyl gallates were predominantly competitive inhibitors of oxygen for uric acid formation and gallic acid and alkyl gallates equally inhibited superoxide anion generation, we deduced that galloyl moiety of gallic acid and alkyl gallates bound superoxide generation site in FAD-binding domain of xanthine oxidase. Binding of gallic acid and alkyl gallates to FADH2 in the enzyme can easily reduce the enzyme, xanthine oxidase, and cannot prevent the binding of the first oxygen molecule to the site since oxygen is so small and reactive. We propose that FADH2 in the reduced oxidase smoothly reduces first oxygen molecule to hydrogen peroxide (A pathway) rather than reducing the second oxygen molecule to superoxide anion (B pathway) as shown in Fig. (8 ).

).

2.3. Chelation of Transition Metal Ions

Alkyl gallates are known to chelate transition metal ions which are powerful promoters of free radical damage in foods [41Aruoma OI, Halliwell B. DNA damage and free radicals Chem Brit 1991; 27: 149-50.]. Alkyl gallates may suppress the superoxide-derived Fenton reaction, which is currently believed to be the most important route to active oxygen species [42Afanas’ev I, Dorozhko AI, Brodskii AV, Kostyul VA, Potapovitch AI. Chelating and free radical scavenging mechanisms

of inhibitory action of rutin and quercetin in lipid peroxidation Biochem Pharmacol 1989; 38: 1763-9.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(89)90410-3] ]. Thus, metal chelation may play a large role in determining the antioxidant activity [43Arora A, Nair MG, Strasburg GM. Structure-activity relationships for antioxidant activities of a series of flavonoids a liposomal system Free Rad Biol Med 1998; 24: 1355-63.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00458-9] ]. The chelation ability, rendering the metal ions inactive to participate in free radical generating reactions, demonstrates the considerable advantage of alkyl gallates as antioxidants.

After the alkyl gallates are consumed together with the foods to which they are added as additives, these alkyl gallates are hydrolyzed to the original gallic acid and the corresponding alcohols. Hence, benefits to human health after consumption of alkyl gallates needs to be concerned mainly with gallic acid. Lipid peroxidation is known to be one of the reactions set into motion as a consequence of the formation of free radicals in cells and tissues. Membrane lipids are abundant in unsaturated fatty acids. The free gallic acid still acts as a potent antioxidant in a living system. Lipoxygenases are suggested to be involved in the early event of atherosclerosis by inducing plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation [44Cornicelli JA, Trivedi BK. 15-Lipoxygenase and its inhibition: a novel therapeutic target for vascular disease Curr Pharm Des 1999; 5: 11-20.

[PMID: 10066881] , 45Kris-Etherton PM, Keen CL. Evidence that the antioxidant flavonoids in tea and cocoa are beneficial for cardiovascular health Curr Opin Lipidol 2002; 13: 41-9.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00041433-200202000-00007] [PMID: 11790962] ]. However, gallic acid did not inhibit the linoleic acid peroxidation catalyzed by soybean lipoxygenase-1, indicating that alkyl side chain is essential to elicit the activity. On the other hand, gallic acid was found as the most effective in scavenging superoxide anion generated by xanthine oxidase.

3. DISCUSSION

The major antioxidants are metal chelators and chain-breaking agents acting as hydrogen atom donors [46Huang D, Ou B, Prior R. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays J Agric Food Chem 2005; 53: 1841-56.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf030723c] [PMID: 15769103] ]. By selecting gallic acid as a head portion, both potent scavenging activity and chelation of metals can be added in general regardless of the hydrophobic tail portion. Alkyl gallates such as octyl- and dodecyl-gallates are powerful antioxidative and antimicrobial agents [4Kubo I, Xiao P, Nihei K, Fujita K, Yamagiwa Y, Kamikawa T. Molecular design of antifungal agents J Agric Food Chem 2002; 50: 3992-8.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf020088v] [PMID: 12083872] , 18Kubo I, Xiao P, Fujita K. Antifungal activity of octyl gallate: Structural criteria and mode of action Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2001; 11: 347-50.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-894X(00)00656-9] , 20Fujita K, Kubo I. Antifungal activity of octyl gallate Int J Food Microbiol 2002; 193-201.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00108-3] , 21Kubo I, Fujita K, Nihei K, Masuoka N. Non-antibiotic antibacterial activity of dodecyl gallate Bioorg Med Chem 2003; 11: 573-80.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0968-0896(02)00436-4] , 47Kubo I, Xiao P, Fujita K. Anti-MRSA activity of akyl gallates Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2002; 12: 113-6.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00663-1] -49Kubo I, Fujita K, Nihei K, Nihei A. Antibacterial activity of alkyl gallates against Bacillus subtilis J Agric Food Chem 2004; 52: 1072-6.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf034774l] [PMID: 14995100] ]. This concept was further extended to geranyl gallate (17) since geraniol is reported to increase glutathione S-transferase activity, which is believed to be a major mechanism for chemical carcinogen detoxification [50Zheng GQ, Kenney PM, Lam LK. Potential anticarcinogenic natural products isolated from lemongrass oil and galanga root oil J Agric Food Chem 1993; 41: 153-6.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00026a001] ]. As expected, geranyl gallate exhibited activity against S. choleraesuis, with a maximum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of 50 µg/mL. In this connection, geraniol is found in a large number (>160) of essential oils - such as lemon grass, coriander, lavender and carrot - and is used as food flavoring for baked goods, soft and hard candy, gelatin and pudding, and chewing gum. The antioxidant gallic acid and the glutathion S-transferase inducer geraniol may contribute to reduce cancer risk as well as oxidative damage-related diseases. Antioxidant activity of alkyl gallates was emphasized for food protection but they are equally potent antioxidants in other applications such as cosmeceutical applications. For example, antioxidative antimicrobial agents, octyl- and dodecyl-gallates, were previously reported to inhibit steroid 5α-reductase [51Hiipakka RA, Zhang HZ, Dai W, Dai Q, Liao S. Structure-activity relationship for inhibition of human 5?-reductase by polyphenols Biochem Pharmacol 2002; 63: 1165-76.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-2952(02)00848-1] ]. This inhibitory activity is not related to food protection but they also have the potent lipoxygenase inhibitory activity and the antibacterial activity against Propionibacterium acnes. These gallates can be considered for external use as acne control agents [52Zouboulis CC, Piquero-Martin J. Update and future of systemic treatment Dermatology 2003; 206: 37-53.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000067821] [PMID: 12566804] ]. As an ideal multifunctional agent, both lipoxygenase-1 inhibitory and antimicrobial activities need to be elicited at the same concentration. However, the antimicrobial activity of octyl gallate requires higher concentrations compared to its soybean lipoxygenase-1 inhibitory activity. For example, the maximum fungicidal concentrations (MFCs) against three food related fungi, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Zygosaccharomyces bailii and Aspergillus niger are 89, 177 and 355 µM, respectively [20Fujita K, Kubo I. Antifungal activity of octyl gallate Int J Food Microbiol 2002; 193-201.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00108-3] ].

Gallic acid is known to chelate transition metal ions which are powerful promoters of free radical damage in the human body [53Henle ES, Linn S. Formation, prevention, and repair of

DNA damage by iron/hydrogen peroxide J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 19095-8.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.31.19095] [PMID: 9235895] ]. More specifically, alkyl gallates may prevent cell damage induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) since this can be converted to the more reactive oxygen species, hydroxyl radicals in the presence of these metal ions. In fact, gallic acid was described to scavenge hydrogen peroxide and to inhibit lipid peroxidation [54Sroka Z, Cisowski W. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging, antioxidant and anti-radical activity of some phenolic acids Food Chem Toxicol 2003; 41: 753-8.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00329-0] ]. In connection with this, catechol groups also have iron binding properties in vitro. However, the inhibition of iron absorption in vivo was positively correlated with the presence of galloyl group but not catechol group [55Brune M, Rossander L, Hallberg L. Iron absorption and phenolic compound: Importance of different phenolic structures Eur J Clin Nutr 1989; 43: 547-58.

[PMID: 2598894] ]. The nitric oxide (NO·), a free radical species produced by several mammalian cell types, plays a role in regulation and function. NO· toxicity is mainly mediated by peroxynitrite (ONOO-), formed in the reaction of NO· with O2·-[56Rubbo H, Darley-Usmar V, Freeman BA. Nitric oxide regulation of tissue free radical injury Chem Res Toxicol 1996; 9: 809-20.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/tx960037q] [PMID: 8828915] ]. Gallic acid was previously reported to act as a potent peroxynitrite scavenger [57Heijnen CGM, Haenen GRMM, Vekemans JAJM, Bast A. Peroxynitrite scavenging of flavonoids: structure activity relationship Envirom Toxicol Pharmacol 2001; 10: 199-206.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1382-6689(01)00083-7] ] and to show antiproliferative activity against melanocytes cell lines [58Yáñez J, Vicente V, Alcaraz M, et al. Cytotoxicity and antiproliferative activities of several phenolic compounds against three melanocytes cell lines: relationship between structure and activity Nutr Cancer 2004; 49: 191-9.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327914nc4902_11] [PMID: 15489212] ]. Sulfonation is one of the major phase II conjugative reactions involved in the biotransformation of various endogenous compounds, drugs, and xenobiotics as well as in steroid biosynthesis, catecholamine metabolism, and thyroid hormone homeostasis [59Brix LA, Nicoll R, Zhu X, McManus ME. Structural and functional characterization of human sulfotransferases Chem Biol Inter 1998; 109: 123-7.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00126-9] ]. Gallic acid enhanced the activity of phenolsulfotransferase and exhibited antioxidant activity as determined by the oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay and Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity assay [60Yeh CT, Yen GC. Effects of phenolic acids on human phenolsulfotransferases in relation to their antioxioxidant activity J Agric Food Chem 2003; 51: 1474-9.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf0208132] [PMID: 12590501] ]. Gallic acid was recently described to activate microsomal glutathione S-transferase through oxidative modification of the enzyme [61Shinno E, Shimoji M, Imaizumi N, Kinoshita S, Sunakawa H, Aniya Y. Activation of rat liver microsomal glutathione S-transferase by gallic acid Life Sci 2005; 78: 99-106.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.034] [PMID: 16125204] ]. Despite the advantages summarized, biological significance of gallic acid as an antioxidant in living systems is still largely unknown. Thus, it is not clear if gallic acid is absorbed into the system without being metabolized and delivered to the places where an antioxidant is needed. The relevance of the in vitro experiments in simplified systems to in vivo protection from oxidative damage should be carefully considered.

Finally, the possibility that gallic acid’s adverse effects are a consequence of its potential to act as a prooxidant may need to be considered. Gallic acid and its esters were described to induce apoptosis in human leukemia HL60 RG and to show cytotoxic effects on other cell lines [62 Inoue M, Suzuki R, Koide T, Sakaguchi N, Ogihara Y, Yabe Y. Antioxidant, gallic acid, induced apoptosis in HL-60RG cells Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994; 204: 898-904.- 65Yoshioka K, Kataoka T, Hayashi T, Hasegawa M, Ishii Y, Hibasami H. Induction of apoptosis by gallic acid in human stomach cancer KATO III and colon adenocarcinoma COLO 205 cell lines Oncol Rep 2000; 7: 1221-3.]. In these apoptotic processes, the generation of ROS (reactive oxygen species) is thought to contribute in the initiation of apoptosis [62Inoue M, Suzuki R, Koide T, Sakaguchi N, Ogihara Y, Yabe Y. Antioxidant, gallic acid, induced apoptosis in HL-60RG cells Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994; 204: 898-904., 66Sakaguchi N, Inoue M, Ogihara Y. Reactive oxygen species and intracellular Ca2+, common signals for apoptosis induced by gallic acid Biochem Pharm 1998; 55: 1973-81.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00041-0] , 67Isuzugawa K, Inoue M, Ogihara Y. Catalase contents in cells determine sensitivity to the apoptosis inducer gallic acid Biol Pharm Bull 2001; 24: 1022-6.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1248/bpb.24.1022] [PMID: 11558562] ]. In fact, gallic acid is known to

produce superoxide anion [1Serrano A, Palacios C, Roy G, et al. Derivatives of gallic acid induce apoptosis in tumoral cell lines and inhibit lymphocyte proliferation Arch Biochem Biophys 1998; 350: 49-54.]. On the other hand, alkyl gallates are known to protect the cell damage induced by hydroxy radicals and hydrogen peroxides against dermal fibroblast cells and this protective effect is dependent on the alkyl chain length [68Masaki H, Okamoto N, Sakai S, Sakurai H. Protective effects of hydroxybenzoic acids and their esters on cell damage induced

by hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxides Bull Pharm Bull 1997; 20: 304-8.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1248/bpb.20.304] ]. The biological activities of gallic acid seem to depend upon its behavior as either an antioxidant or a prooxidant [69Yen GC, Duh PD, Tsai HL. Antioxidant and pro-oxidant properties of ascorbic acid and hallic acid Food Chem 2002; 79: 307-13.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00145-0] ]. Thus the relevance of the in vitro experiments in simplified systems should be carefully considered. The results so far obtained indicate that their further evaluation is needed from not only one aspect, but from a whole and dynamic perspective.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Alkyl gallates were available from our previous works [4Kubo I, Xiao P, Nihei K, Fujita K, Yamagiwa Y, Kamikawa T. Molecular design of antifungal agents J Agric Food Chem 2002; 50: 3992-8.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf020088v] [PMID: 12083872] , 70Nihei K, Nihei A, Kubo I. Molecular design of multifunctional food additives Antioxidative antifungal agents J Agric Food Chem 2004; 52: 5011-20.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf049687n] [PMID: 15291468] ]. 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), L-DOPA and methanol were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), EDTA, Tween-20, bovine serum albumin and linoleic acid (purity >99%) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Tris buffer was obtained from Fisher Scientific Co. (Fair Lawn, NJ). Ethanol was purchased from Quantum Chemical Co. (Tuscola, IL).

DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

First, 1 mL of 100 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.5), 1.87 mL of ethanol and 0.1 mL of ethanolic solution of 3mM DPPH were put into a test tube. Then, 0.03 mL of the sample solution (dissolved in DMSO) was added to the tube and incubated at 25 °C for 20 min. The absorbance at 517 nm (DPPH, ε = 8.32 X 103 M-1cm-1) was recorded. As a control, 0.03 mL of DMSO without sample was added to a tube. From decrease of the absorbance, scavenging activity was calculated and expressed as scavenged DPPH molecules per a test molecule.

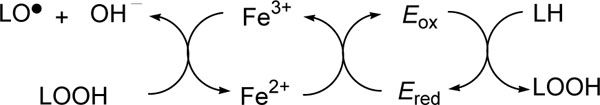

Lipoxygenase Assay

Throughout the experiment, linoleic acid was used as a substrate. In spectophotometric experiment, the oxygenase activity of the soybean lipoxygenase was monitored at 25 ºC by Spectra MAX plus spectrophotometer (Molecular device, Sunnyvale, CA). 13-Hydroperoxyoctadecadienoic acid (13-HPOD: λmax = 234 nm, ( = 25 mM-1cm-1) was prepared enzymatically by described procedure [71Gibian MJ, Galaway RA. Steady-state kinetics lipoxygenase oxygenation of unsaturated fatty acid Bio-chemistry 1976; 15: 4209-14.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bi00664a012] [PMID: 822867] ] and stored in ethanol at -18 ºC. Commercial lipoxygenase contains a non-heme ferrous ion (Ered) that must be oxidized to yield the catalytically active ferric enzyme (Eox) and therefore a catalytic amount of LOOH (13-HPOD) is usually added as a cofactor to LH (linoleic acid, a substrate). Alkyl gallates chelate both ferric and ferrous ions.

The enzyme assay was performed as previously reported [72Ruddat VC, Whitman S, Holman TR, Bernasconi CF. Stopped-flow kinetics investigations of the activation of soybean lipoxygenase-1 and the influence of inhibitors on the allosteric site Biochemistry 2003; 42: 4172-8.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bi020698o] [PMID: 12680771] ] with slight modification. In general, 5 μL of an ethanolic inhibitor solution was mixed with 54 μL of 1 mM stock solution of linoleic acid and 2.936 mL of 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) in a quartz cuvet. Then, 5 μL of 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer solution (pH 8.0) of lipoxygenase (1.02 μM) was added. The resultant solution was mixed well and the linear increase of absorbance at 234 nm, which express the formation of conjugated diene hydroperoxide (13-HPOD), was measured continuously. Lag period shown on lipoxygenase reaction [73Frieden C. Kinetic aspects of regulation of metabolic processes The hysteretic enzyme concept J Biol Chem 1970; 245: 5788-99.

[PMID: 5472372] ] was excluded for the determination of initial rates. The stock solution of linoleic acid was prepared with methanol and Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8.0, and, then, total methanol content in the final assay was adjusted below 1.5%.

To determine the kinetic parameters associated with slow-binding inhibition of soybean lipoxygenase-1, progress curves with 25 or more data points (≤ 300), typically at 2 second intervals, were obtained at several inhibitor concentrations and fixed concentration of substrate. The data were analyzed using the nonlinear regression program of Sigma Plot (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) to give the individual parameters for each progress curve; vi (initial velocity), vs (steady-state velocity), kobs (apparent first-order rate constant for the transition from vi to vs), A (absorbance at 234 nm and/or O2 uptake), A0 (included to correct any possible deviation of the baseline), and Kiapp (apparent Ki) according to eq 1 and 2 [74Toda S, Kumura M, Ohnishi M. Effects of phenolcarboxylic acids on superoxide anion Planta Med 1991; 57: 8-10.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-960005] [PMID: 1648246] ]:

Assay of Superoxide Anion Generated by Xanthine Oxidase

Xanthine oxidase (EC 1.1.3.22, Grade IV) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. Superoxide anion was generated enzymatically by xanthine oxidase system. The reaction mixture consisted of 2.70 mL of 40 mM sodium carbonate buffer containing 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 10.0), 0.06 mL of 10 mM xanthine, 0.03 mL of 0.5 % bovine serum albumin, 0.03 mL of 2.5 mM nitroblue tetrazolium and 0.06 mL of sample solution (dissolved in DMSO). To the mixture at 25 °C, 0.12 mL of xanthine oxidase (0.04 units) was added, and the absorbance at 560 nm was recorded for 90 sec (by formation of blue formazan) [74Toda S, Kumura M, Ohnishi M. Effects of phenolcarboxylic acids on superoxide anion Planta Med 1991; 57: 8-10.

[http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-960005] [PMID: 1648246] ]. Control experiment was carried out by replacing sample solution with same amount of DMSO.

Uric Acid Generated by Xanthine Oxidase

The reaction mixture consisted of 2.76 mL of 40 mM sodium carbonate buffer containing 0.1mM EDTA (pH 10.0), 0.06 mL of 10 mM xanthine and 0.06 mL of sample solution (dissolved in DMSO). The reaction was started by the addition of 0.12 mL of xanthine oxidase (0.04 Unit), and the absorbance at 293 nm was recorded for 90 sec. In the case of dodecyl gallate, the concentration of DMSO was increased to 8 % because of the low solubility of dodecyl gallate in the reaction mixture. It should be noted that the measurement of xanthine oxidase inhibitory activity was possible only for concentrations <0.2 mM due to overlapping absorbance of alkyl gallates and uric acid at 293 nm.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work was presented in part at the Symposium of Diet and the Prevention of Gender Related Cancers in Division of Agricultural and Food Chemistry for the 222nd ACS National Meeting in Chicago, Il. The authors are grateful to Dr. H. Haraguchi for performing autoxidation assay at earlier stage of the work.

REFERENCES

| [1] | Serrano A, Palacios C, Roy G, et al. Derivatives of gallic acid induce apoptosis in tumoral cell lines and inhibit lymphocyte proliferation Arch Biochem Biophys 1998; 350: 49-54. |

| [2] | Huang D, Ou B, Prior R. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays J Agric Food Chem 2005; 53: 1841-56. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf030723c] [PMID: 15769103] |

| [3] | Aruoma OI, Murcia A, Butler J, Halliwell B. Evaluation of the antioxidant and prooxidant actions of gallic acid and its derivatives J Agric Food Chem 1993; 41: 1880-5. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00035a014] |

| [4] | Kubo I, Xiao P, Nihei K, Fujita K, Yamagiwa Y, Kamikawa T. Molecular design of antifungal agents J Agric Food Chem 2002; 50: 3992-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf020088v] [PMID: 12083872] |

| [5] | Kubo I, Chen Q X, Nihei K. Molecular design of antibrowning agents: Antioxidative tyrosinase inhibitors Food Chem 2003; 81: 241-7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00418-1] |

| [6] | Gray JI, Pearson AM. Rancidity and warmed-over flavor Avd Meat Res 1987; 3: 221-69. |

| [7] | Faustman C, Cassens RG, Schaefer DM, Buege DR, Williams SN, Scheller KK. Improvement of pigment and lipid stability in Holstein steer beef by dietary supplementation with vitamin E J Food Sci 1989; 54: 858-62. |

| [8] | Monahan FJ, Gray JI, Booren AM, et al. Influence of dietary treatment on cholesterol oxidation in pork JAgric Food Chem 1992; 40: 1310-5. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00020a003] |

| [9] | Tsuda T, Ohshima K, Kawakishi S, Osawa T. Antioxidative pigments isolated from the seeds of Phaseolus vulgaris LJ Agric Food Chem 1994; 42: 248-51. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00038a004] |

| [10] | Machlin L, Bendich A. Free radical tissue damage: protective role of antioxidant nutrients FASEB J 1987; 1: 441-5. [PMID: 3315807] |

| [11] | Slater TF, Cheeseman KH. Free radical mechanisms in relation to tissue injury Proc Natr Soc 1987; 46: 1-12. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/PNS19870003] [PMID: 3033678] |

| [12] | Sugawara H, Tobise K, Minami H, Uekita K, Yoshie H, Onodera S. Diabetes mellitus and reperfusion injury increase the level of active oxygen-induced lipid peroxidation in rat cardiac membranes J Clin Exp Med 1992; 163: 237-8. |

| [13] | Kok FJ, Van Poppel G, Melse J, et al. Do antioxidants and polyunsaturated fatty acids have a combined association with coronary arteriosclerosis? Arteriosclerosis 1991; 86: 85-90. |

| [14] | Yagi K. Lipid peroxides and human disease Chem Phys Lipid 1987; 45: 337-41. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0009-3084(87)90071-5] |

| [15] | Yoshida T, Mori K, Hatano T, et al. Studies on inhibition mechanism

of autoxidation by tannins and flavonoids V. Radical-scavenging effects of tannins and related polyphenols on 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical Chem Pharm Bull 1989; 37: 1919-21. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1248/cpb.37.1919] |

| [16] | Savi LA, Leal PC, Vieira TO, et al. Evaluation of anti-herpetic and antioxidant activities, and cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of synthetic alkyl-esters of gallic acid Arztl Forsch 2005; 55: 66-75. |

| [17] | Gunckel S, Santander P, Cordano G, et al. Antioxidant activity of gallates an electrochemical study in aqueous media Chem Biol Inter 1998; 114: 45-59. |

| [18] | Kubo I, Xiao P, Fujita K. Antifungal activity of octyl gallate: Structural criteria and mode of action Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2001; 11: 347-50. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-894X(00)00656-9] |

| [19] | Fujita K, Kubo I. Plasma membrane injury by nonyl gallate

in Saccharomyces cerevisiae J Appl Microbiol 2002; 92: 1035-42. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01614.x] [PMID: 12010543] |

| [20] | Fujita K, Kubo I. Antifungal activity of octyl gallate Int J Food Microbiol 2002; 193-201. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00108-3] |

| [21] | Kubo I, Fujita K, Nihei K, Masuoka N. Non-antibiotic antibacterial activity of dodecyl gallate Bioorg Med Chem 2003; 11: 573-80. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0968-0896(02)00436-4] |

| [22] | Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Paganga G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acid Free Radic Biol Med 1996; 20: 933-56. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0891-5849(95)02227-9] |

| [23] | Grechkin A. Recent developments in biochemistry of the plant lipoxygenase pathway Prog Lipid Res 1998; 37: 317-52. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0163-7827(98)00014-9] |

| [24] | Min B, Ahn DU. Mechanism of lipid peroxidation in meat and meat products - A review Food Sci Biotechnol 2005; 14: 152-63. |

| [25] | Witting LA, Pryor W A, Eds. Vitamin E and lipid antioxidants in free-radical-initiated reactions In Free Radicals in Bilogy 1980; 4: 295-319. |

| [26] | Haraguchi H, Hashimoto K, Yagi A. Antioxidative substances in leaves of Polygonum hydropiper J Agric Food Chem 1992; 40: 1349-51. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00020a011] |

| [27] | Shibata D, Axelrod B. Plant lipoxygenases J Lipid Mediat Cell Signal 1995; 12: 213-28. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0929-7855(95)00020-Q] |

| [28] | Richard-Forget F, Gauillard F, Hugues M, Jean-Marc T, Boivin P, Nicolas J. Inhibition of horse bean and germinated barley lipoxygenases by some phenolic compounds J Food Sci 1995; 60: 1325-9. |

| [29] | Grechkin A. Recent developments in biochemistry of the plant lipoxygenase pathway Prog Lipid Res 1998; 37: 317-52. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0163-7827(98)00014-9] |

| [30] | Axelrod B, Cheesbrough TM, Laakso S. Lipoxygenase from soybeans Methods Enzymol 1981; 71: 441-57. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0076-6879(81)71055-3] |

| [31] | Ha TJ, Nihei K, Kubo I. Lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of octyl gallate J Agric Food Chem 2004; 52: 3177-81. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf034925k] [PMID: 15137872] |

| [32] | Whitman S, Gezginci M, Timmermann B, Holman TR. Structure-activity relationship studies of nordihydroguaiaretic acid

inhibitors toward soybean, 12-human, and 15-human lipoxygenase J Med Chem 2002; 45: 2659-61. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jm0201262] [PMID: 12036375] |

| [33] | Ruddat VC, Whitman S, Holman TR, Bernasconi CF. Stopped-flow kinetics investigations of the activation of soybean lipoxygenase-1 and the influence of inhibitors on the allosteric site Biochemistry 2003; 42: 4172-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bi020698o] [PMID: 12680771] |

| [34] | Grunfeld S, Hamilton CA, Mesaros S, et al. Rple of superoxide in the depressed nitric oxide production by the endothelium of genetically hypertensive rats Hepertesion 1995; 26: 854-7. |

| [35] | Hille R, Massey V. Studies on the oxidative half-reaction of xanthine oxidase J Biol Chem 1981; 256: 9090-5. [PMID: 6894924] |

| [36] | Masuoka N, Nihei K, Kubo I. Xanthine oxidase inhibitory activity of alkyl gallates Mol Nutr Food Sci 2006; 50: 725-31. |

| [37] | Enroth C, Eger BT, Okamoto K, Nishino T, Pai EF. Crystal structures of bovine milk xanthine dehydrogenase and xanthine oxidase: Structure-based mechanism of conversion Proc Nat Acad Sci 2000; 97: 10723-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.20.10723] [PMID: 11005854] [PMCID: PMC27090] |

| [38] | McGovern SL, Caselli E, Grigorieff N, Shoichet BK. A common mechanism underlying promiscuous inhibitors from

virtual and high-throughput screening J Med Chem 2002; 45: 1712-22. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jm010533y] [PMID: 11931626] |

| [39] | Fraaiji MW, van den Heuvel RHH, van Berkel WJH, Mattevi A. Structural analysis of flavinylation in vanillyl-alcohol oxidase J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 38654-8. |

| [40] | Abe I, Seki T, Noguchi H. Potent and selective inhibition of squalene epoxidase by synthetic galloyl esters Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000; 270: 137-40. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.2000.2399] [PMID: 10733917] |

| [41] | Aruoma OI, Halliwell B. DNA damage and free radicals Chem Brit 1991; 27: 149-50. |

| [42] | Afanas’ev I, Dorozhko AI, Brodskii AV, Kostyul VA, Potapovitch AI. Chelating and free radical scavenging mechanisms

of inhibitory action of rutin and quercetin in lipid peroxidation Biochem Pharmacol 1989; 38: 1763-9. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(89)90410-3] |

| [43] | Arora A, Nair MG, Strasburg GM. Structure-activity relationships for antioxidant activities of a series of flavonoids a liposomal system Free Rad Biol Med 1998; 24: 1355-63. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00458-9] |

| [44] | Cornicelli JA, Trivedi BK. 15-Lipoxygenase and its inhibition: a novel therapeutic target for vascular disease Curr Pharm Des 1999; 5: 11-20. [PMID: 10066881] |

| [45] | Kris-Etherton PM, Keen CL. Evidence that the antioxidant flavonoids in tea and cocoa are beneficial for cardiovascular health Curr Opin Lipidol 2002; 13: 41-9. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00041433-200202000-00007] [PMID: 11790962] |

| [46] | Huang D, Ou B, Prior R. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays J Agric Food Chem 2005; 53: 1841-56. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf030723c] [PMID: 15769103] |

| [47] | Kubo I, Xiao P, Fujita K. Anti-MRSA activity of akyl gallates Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2002; 12: 113-6. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00663-1] |

| [48] | Kubo I, Fujita K, Nihei K. Anti-Salmonella activity of alkyl gallates J Agric Food Chem 2002; 50: 6692-6. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf020467o] [PMID: 12405763] |

| [49] | Kubo I, Fujita K, Nihei K, Nihei A. Antibacterial activity of alkyl gallates against Bacillus subtilis J Agric Food Chem 2004; 52: 1072-6. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf034774l] [PMID: 14995100] |

| [50] | Zheng GQ, Kenney PM, Lam LK. Potential anticarcinogenic natural products isolated from lemongrass oil and galanga root oil J Agric Food Chem 1993; 41: 153-6. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf00026a001] |

| [51] | Hiipakka RA, Zhang HZ, Dai W, Dai Q, Liao S. Structure-activity relationship for inhibition of human 5?-reductase by polyphenols Biochem Pharmacol 2002; 63: 1165-76. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-2952(02)00848-1] |

| [52] | Zouboulis CC, Piquero-Martin J. Update and future of systemic treatment Dermatology 2003; 206: 37-53. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000067821] [PMID: 12566804] |

| [53] | Henle ES, Linn S. Formation, prevention, and repair of

DNA damage by iron/hydrogen peroxide J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 19095-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.31.19095] [PMID: 9235895] |

| [54] | Sroka Z, Cisowski W. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging, antioxidant and anti-radical activity of some phenolic acids Food Chem Toxicol 2003; 41: 753-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00329-0] |

| [55] | Brune M, Rossander L, Hallberg L. Iron absorption and phenolic compound: Importance of different phenolic structures Eur J Clin Nutr 1989; 43: 547-58. [PMID: 2598894] |

| [56] | Rubbo H, Darley-Usmar V, Freeman BA. Nitric oxide regulation of tissue free radical injury Chem Res Toxicol 1996; 9: 809-20. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/tx960037q] [PMID: 8828915] |

| [57] | Heijnen CGM, Haenen GRMM, Vekemans JAJM, Bast A. Peroxynitrite scavenging of flavonoids: structure activity relationship Envirom Toxicol Pharmacol 2001; 10: 199-206. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1382-6689(01)00083-7] |

| [58] | Yáñez J, Vicente V, Alcaraz M, et al. Cytotoxicity and antiproliferative activities of several phenolic compounds against three melanocytes cell lines: relationship between structure and activity Nutr Cancer 2004; 49: 191-9. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327914nc4902_11] [PMID: 15489212] |

| [59] | Brix LA, Nicoll R, Zhu X, McManus ME. Structural and functional characterization of human sulfotransferases Chem Biol Inter 1998; 109: 123-7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00126-9] |

| [60] | Yeh CT, Yen GC. Effects of phenolic acids on human phenolsulfotransferases in relation to their antioxioxidant activity J Agric Food Chem 2003; 51: 1474-9. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf0208132] [PMID: 12590501] |

| [61] | Shinno E, Shimoji M, Imaizumi N, Kinoshita S, Sunakawa H, Aniya Y. Activation of rat liver microsomal glutathione S-transferase by gallic acid Life Sci 2005; 78: 99-106. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.034] [PMID: 16125204] |

| [62] | Inoue M, Suzuki R, Koide T, Sakaguchi N, Ogihara Y, Yabe Y. Antioxidant, gallic acid, induced apoptosis in HL-60RG cells Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994; 204: 898-904. |

| [63] | Sakaguchi N, Inoue M, Isuzugawa K, Ogihara Y, Hosaka K. Cell death-inducing activity by gallic acid derivatives Biol Pharm Bull 1999; 22: 471-5. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1248/bpb.22.471] [PMID: 10375166] |

| [64] | Ohno Y, Fukuda K, Takemura G, et al. Induction of apoptosis by gallic acid in lung cancer cells Anticancer Drugs 1999; 10: 845-51. |

| [65] | Yoshioka K, Kataoka T, Hayashi T, Hasegawa M, Ishii Y, Hibasami H. Induction of apoptosis by gallic acid in human stomach cancer KATO III and colon adenocarcinoma COLO 205 cell lines Oncol Rep 2000; 7: 1221-3. |

| [66] | Sakaguchi N, Inoue M, Ogihara Y. Reactive oxygen species and intracellular Ca2+, common signals for apoptosis induced by gallic acid Biochem Pharm 1998; 55: 1973-81. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00041-0] |

| [67] | Isuzugawa K, Inoue M, Ogihara Y. Catalase contents in cells determine sensitivity to the apoptosis inducer gallic acid Biol Pharm Bull 2001; 24: 1022-6. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1248/bpb.24.1022] [PMID: 11558562] |

| [68] | Masaki H, Okamoto N, Sakai S, Sakurai H. Protective effects of hydroxybenzoic acids and their esters on cell damage induced

by hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxides Bull Pharm Bull 1997; 20: 304-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1248/bpb.20.304] |

| [69] | Yen GC, Duh PD, Tsai HL. Antioxidant and pro-oxidant properties of ascorbic acid and hallic acid Food Chem 2002; 79: 307-13. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00145-0] |

| [70] | Nihei K, Nihei A, Kubo I. Molecular design of multifunctional food additives Antioxidative antifungal agents J Agric Food Chem 2004; 52: 5011-20. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf049687n] [PMID: 15291468] |

| [71] | Gibian MJ, Galaway RA. Steady-state kinetics lipoxygenase oxygenation of unsaturated fatty acid Bio-chemistry 1976; 15: 4209-14. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bi00664a012] [PMID: 822867] |

| [72] | Ruddat VC, Whitman S, Holman TR, Bernasconi CF. Stopped-flow kinetics investigations of the activation of soybean lipoxygenase-1 and the influence of inhibitors on the allosteric site Biochemistry 2003; 42: 4172-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bi020698o] [PMID: 12680771] |

| [73] | Frieden C. Kinetic aspects of regulation of metabolic processes The hysteretic enzyme concept J Biol Chem 1970; 245: 5788-99. [PMID: 5472372] |

| [74] | Toda S, Kumura M, Ohnishi M. Effects of phenolcarboxylic acids on superoxide anion Planta Med 1991; 57: 8-10. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-960005] [PMID: 1648246] |